Health Policy: Prescription Drug Pricing

Shashank Soma, MSIII - Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine

EMRA MSC Legislative Coordinator, 2021-22

Remember the EpiPen controversy of 2016? After acquiring the rights to the EpiPen, Mylan Pharmaceuticals steadily increased the wholesale price of a 2-pack from $103.50 to $608.61 over 7 years, or by roughly 500%. When uncovered by Congress, Mylan was publicly excoriated, investigated, sued, and eventually fined $465 million. Another memorable example may be Martin Shkreli, the so-called “Pharma Bro” who increased the price of Daraprim by over 5,000%. At some point or another we’ve all wondered: how is this even possible?

How Are Drug Prices Set in the U.S.?

The U.S. is different from almost all other developed countries in that it relies on market competition to determine drug prices, rather than extensively regulating pricing. In other words, drug companies compete for market advantage by offering the lowest possible prices. The problem is that this only holds true for generic drugs. Brand name or specialty drugs are offered exclusively by a single manufacturer due to intellectual property protections, allowing them to basically dictate the price at which they want to sell the drug. As a result, unbranded generics accounted for 84% of drugs sold in the U.S. but only 12% of drug spending, with the rest being due to incredibly expensive biologic therapies. Even though patents give companies a limited monopoly on a new drug for 20-34 years, drugmakers frequently circumvent this by slightly altering medication formulas to allow them to obtain new patents that extend their exclusive hold over the drug.

Balancing Costs & Innovation

Pharmaceutical companies often justify high drug prices by quoting the cost of research & development (R&D) of a new drug, which averages about $1.3 billion. However, this does not take into account the massive profits taken in by the pharmaceutical industry or the roughly $13.5 billion annually spent on heavy marketing to clinicians.

Because many other countries have universal healthcare and laws in place that allow their governments the power to regulate drug prices, companies are often unable to recoup their initial R&D costs abroad. Consequently, it is felt that the American healthcare system effectively subsidizes the drug prices of foreign countries.

The Orphan Drug Act was passed giving drugmakers tax breaks, higher patent protection, and research subsidies to develop treatments for rare diseases. This helped ensure that drug development does not overlook rare disease treatments in lieu of treatments for more common diseases with higher earnings potential. Because patients with rare diseases have few, if any, other treatment options and with almost 93% of insurers covering these drugs, the number of approved orphan drugs increasing from 38 in 1983 to 1,129 in 2004. Though the law is considered a dramatic success, it undoubtedly contributed to the massive cost of specialty drugs in the U.S.

Hidden Players

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are essentially the middlemen between drugmakers and healthcare providers. By representing multiple employers, insurers, and pharmacies, PBMs consolidate demand which gives them greater leverage to negotiate better deals with drugmakers. PBMs assert that they pass on much of these savings to the consumers, which is partially true. However, PBMs have received criticism for their lack of transparency about price negotiations, exclusion lists preventing pharmacies from offering cheaper drug alternatives, and for creating formularies that do not necessarily offer the lowest cost drugs. PBMs argue that as a cog in the business of American healthcare, they help reduce costs for consumers. The role of a middleman, however, is inherently economically inefficient. The system as a whole would therefore spend less money on fees and rebates if drugmakers, pharmacies, and healthcare providers worked directly with one another rather than through PBMs.

Another influential player in prescription drug policies is the pharmaceutical lobby, one of the most powerful political groups in the entire country. In the modern era, prescription drug pricing first became a major issue in the 1990s. Despite an overwhelming majority of Americans, and even Congress, agreeing that drug prices are too high, there has been no significant legislation on the issue due to forceful and effective lobbying by the pharmaceutical lobby. For instance, when the Affordable Care Act was being negotiated in 2009, lawmakers obtained drugmaker support for the bill by promising not to import lower-cost drugs from other countries.

Why We Care

Of the 49 most common top-selling brand-name drugs, 78% increased in price by over 50% and 44% more than doubled. Between 2000 and 2017 consequently, prescription drug spending in the U.S. jumped by 76% and accounted for over 10% of all healthcare spending. Drug prices are projected to continue to rise in upcoming years, disproportionately relative both to inflation and overall healthcare spending.

In the ED, we so often see the patients having to choose between paying for medications or food, or medications or rent. Patients being unable to afford or take the medications they need for chronic disease management leads to increased ED usage, unnecessary healthcare costs, poorer outcomes, and decreased quality of life. Drug pricing reform is desperately needed, to ensure equitable access to potentially lifesaving medications for patients, streamline healthcare delivery, and better balance costs with pharmaceutical innovation.

References

- Mulcahy AW, Whaley CM, Gizaw M, et al. International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons. RAND Corporation. 2021. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2956.html

- Wineinger, NE, Zhang Y, Topol EJ. Trends in Prices of Popular Brand-Name Prescription Drugs in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194791.

- Lieberman SM, Ginsburg PB, Patel KK. Balancing Lower U.S. Prescription Drug Prices And Innovation – Part 1. Health Affairs. 2020; doi: 10.1377/hblog20201123.804451.

- Werble C. Pharmacy Benefit Managers. Health Affairs. 2017; doi: 10.1377/hpb20171409.000178

- ACEP. Prescription Drug Pricing. Patient Care Policy Statements. 2018. Available at: https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/prescription-drug-pricing/

Related Content

May 02, 2023

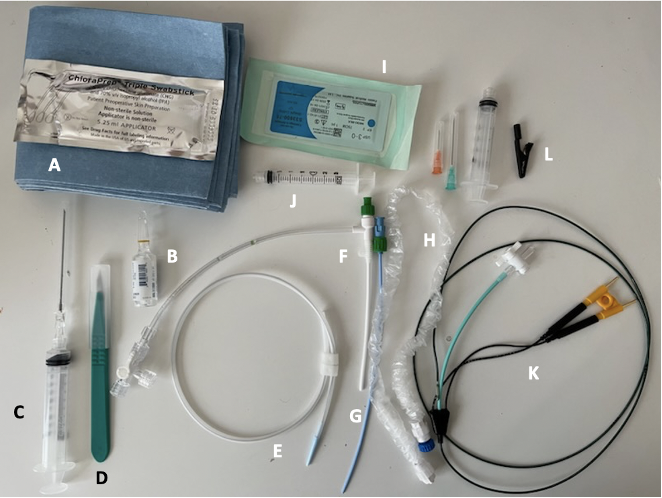

Critical Care Device Series: Transvenous Pacemaker

Temporary transvenous pacing (TTVP) utilizes central venous access to pass an electrode into the right ventricle. TTVPs are one of the most infrequently performed procedures by emergency physicians; however, it is essential for those working in any setting with critically ill patients to be well-equipped to perform this procedure emergently.