Second Victim Syndrome

Chapter 8 Audio

INTRODUCTION

Patient safety events and/or medical errors are inevitable during the course of a medical career. Medical errors are a significant source of morbidity and mortality and have been cited by some sources as the third leading cause of death in the United States.1 Whether the event or error is related to a system failure or a human error, part of the physician experience involves making mistakes. This simple and critical concept is rarely discussed during medical school and residency training. Patients may perceive their doctors as infallible experts. Physicians similarly tend to expect the same unrealistic levels of perfection from themselves. This false sense of perfection collides with the realities of being human and working within complex health care systems. As described in the book “To Err is Human” in 2000, there are not bad people working in health care, rather good people working in bad systems that need to be made safer.2 But how do medical errors and adverse events affect these providers, and how can we effectively support our providers following an error or adverse event?

“Virtually every practitioner knows the sickening realization of making a bad mistake. You feel singled out and exposed…..You agonize about what to do…… Later, the event replays itself over and over in your mind.”

WHAT IS SECOND VICTIM SYNDROME (SVS)?

In 2000, Albert Wu coined the term, “second victim.”2 In any patient safety event/medical error, the first victim is the patient. The second victim is the provider (a resident, attending physician, advanced practice provider, nurse, paramedic, etc.) who is involved in a patient safety event/medical error who subsequently becomes traumatized by the event. Examples of patient safety events/medical errors include situations such as incorrect medication dosages, missed diagnosis, incorrect medical management, accidental harm during a procedure, among several others. These types of cases are unforgettable and can leave lasting emotional scars on providers.

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF SVS ON PROVIDERS?

Several studies have shown that second victims can experience significant emotional distress, including but not limited to anxiety, depression, guilt, sleep disturbances, loss of confidence in their practice, and decreased job satisfaction.3,4

These emotional effects, depending on the nature of the case and severity of injury to the patient, can last for weeks or up to several years. 4 These intrusive feelings can affect a provider’s perception of their own professional reputation, lead to a change in clinical practice, contribute to fear of losing one’s job, and even contemplation of leaving one’s career. Isolation, depression, and suicidality have all been associated with second victim events. 3,4,5 In addition, studies have shown that providers who are identified as second victims have a higher risk of being involved in a subsequent patient safety event/medical error.5 This is secondary to the fact that second victims are often preoccupied by their emotions and have a harder time focusing on decision-making while distressed.

In medicine, determining the root cause of errors is important to help prevent the occurrence of future errors. In an ideal setting, errors would be avoided altogether. However, we know through our collective experiences that this is rarely the case. From a systems standpoint, patient safety measures are developed through protocols, pathways, and other interventions often in response to an adverse event. As our system has been hard at work focusing on patient safety and quality, our medical culture has been lacking in its support of the providers involved in these cases. Another challenging aspect of these events involves the disclosure and reporting of an error. In one study, only about one-third of trainees receive formal training in medical error disclosure, though over 90% expressed interest in receiving disclosure training. 7 Students, trainees, or attending physicians who lack disclosure training or who function in an unsupportive and punitive clinical environment will be less likely to report medical errors, which ultimately leads to less effective prevention of future errors and patient harm reduction.

WHY ARE RESIDENTS AT RISK?

Residents are a particularly high-risk population for Second Victim Syndrome. As a group, residents are in the learning phase and are expected to make mistakes during their training given their relative levels of inexperience combined with high levels of clinical accountability. In addition, residency can be challenging given the high demands of clinical workload, sleep/fatigue irregularities, potential loss of self-care, and possible strain on relationships who contribute to a much needed support network. Residents may experience considerably greater negative consequences following an adverse event if they are sleep-deprived, without a support system, and lacking healthy coping strategies. According to one study, the prevalence of fourth-year students involved in a medical error was 78% - compared to 98% of residents.7 A survey of more than 3100 physicians from the U.S. and Canada found that 81% of those who had been involved in a clinical event (serious error, minor error, or near miss) experienced some degree of emotional distress.8 Second Victim Syndrome is well described and highly prevalent in our clinical environment.

In the most devastating of cases, second victims can harbor debilitating levels of distress that ultimately could lead to suicide. Numerous reports in the literature discuss providers (nurses, residents, attending physicians) who died by suicide following a significant event that led to patient harm.

HOW DO WE IDENTIFY SECOND VICTIMS?

Second victims may display similar emotions and behaviors to those who are experiencing burnout. Providers may experience emotional lability, isolation, a decreased ability to focus, and may withdraw themselves from their support networks.

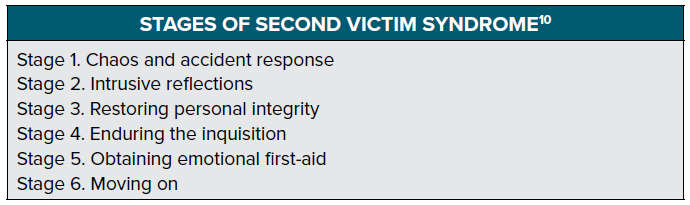

Through their research, Scott and colleagues identified a common second victim pathway of coping toward recovery.10 They found that although the participants in their study had unique coping styles, they seemed to share a fairly predictable recovery pattern: (1) chaos and accident response; (2) intrusive reflections, (3) restoring personal integrity, (4) enduring the inquisition, (5) obtaining emotional first aid and (6) moving on.

During the first stage of “chaos and accident response,” the provider will experience turmoil, distraction, and will often self-chastise as a result of the event. During this stage, the provider may ask themselves, “How and why did this happen?” The second stage of “intrusive reflections” is defined by “a period of haunted re-enactments, often with feelings of internal inadequacy and periods of self-isolation.” 10 Providers in the second stage may begin asking, “How did I miss this and could this have been prevented?” During the critical third stage of “restoring personal integrity,” the second victim will question their reputation and acceptance within the workplace. Questions such as “What will others think?”, “Will I ever be trusted again?”, and “How much trouble am I in?” are pervasive during this stage. It is during this stage that providers will begin to seek support from a trusted individual such as a colleague, supervisor, family member or friend. Without a positive supportive environment during this stage, providers may find extreme difficulty moving forward from the event.10 The first three stages may occur in succession or simultaneously.

Stage four of the recovery process is known as “enduring the inquisition” when the second victim begins to focus on the potential repercussions affecting job security, licensure, and future litigation. During this stage, it is critical that the provider understands what to expect and how to obtain support through these stressful encounters. Stage five involves “obtaining emotional first aid.” Peer supporters, patient safety, and risk management all play a crucial role in ensuring the provider has a safe space to recover from the event. In the final stage, “moving on,” the provider will either thrive, survive, or drop out. If adequate support and guidance are provided throughout this process, the provider will ideally continue to thrive through professional and personal growth following the event.

HOW DO WE PROVIDE SUPPORT TO SECOND VICTIMS?

Studies have shown that the most effective management of second victims includes the support of providers by peer colleagues from within their own specialty.11 While support from friends, significant others and supervisors are important, most providers prefer support from a trusted colleague, which has prompted several institutions to implement robust second victim response teams. 11,12 Receiving support from a colleague from within one’s own specialty offers a sense of shared understanding about the complex nature of patient care. It also normalizes the situation for the affected provider. Peer support teams that are trained to provide emotional first aid are also incredibly beneficial. 11,12 Creating a strong support network within medical school, residency, and future clinical practice can help to lessen the effects of Second Victim Syndrome. Normalizing mistakes and encouraging the supportive discussion about adverse patient events and medical errors has also been shown to improve the effects of SVS. Morbidity and mortality (M&M) or Patient Safety conferences following events during a resident’s training need to be thoughtful, supportive, and focused on improving patient safety and encouraging a “just culture” rather than pointing blame at the provider.

One organizational model developed at the University of Missouri to address second victimization involves a tiered support system. 13 At the first tier, local unit or departmental clinical peers would be expected to provide a culture of support rather than shame and blame on a daily basis. The second tier of support would come from peer supporters, patient safety officers, and risk managers who are trained to provide one-on-one crisis intervention, mentorship, and group debriefings after an adverse event. Finally, the third tier involves an expedited referral network comprising clinical psychologists, employee assistant programs, chaplains, and social workers who could mobilize to provide further aid to the affected provider.

Culture change, one could argue, is ultimately more important than any single intervention. The traditional culture of shame and blame aimed at providers who have experienced a second victim phenomenon should be rapidly replaced by a movement toward a “just culture.” A just culture balances the need for an open and honest reporting environment with the end of a quality learning environment. Rather than pointing blame at an individual provider, a just culture encourages individuals to disclose medical errors in a supportive environment to help promote rather than impede a culture of safety. A framework of just culture helps to balance the accountability for both the individuals and the organization in order to promote patient safety by improving the workplace system.14 If individuals continuously fear retribution, they will be unlikely to disclose errors that could provide valuable insight into valuable system re-designs. Conversely, in a supportive environment, a provider will feel more inclined to discuss an adverse event in the interest of organizational patient safety.

CONCLUSION

Although several second victim programs do currently exist, it is not necessary to have this infrastructure to promote a healthy and supportive work environment at one’s local institution. Every individual can contribute by providing peer support to a colleague who has experienced a second victim event. By being an empathetic listener, removing judgment and blame, and sharing a personal experience of our own errors, we can all serve each other well in our medical careers and community. As providers in medicine, we have difficult jobs, we will make errors, and we will be involved in cases with adverse outcomes. It is important to always remember we are not alone and these mistakes do not define us as providers. With the proper second victim support, we can ultimately create a safer space for ourselves and for our patients.

REFERENCES

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

- Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academy Press. 2000.

- Wu AW. Medical error: The second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. Br Med J. 2000;320(7237):726–727.

- Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, Dunagan WC, Levinson W, Fraser VJ, Gallagher TH. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(8):467-76.

- Pratt SD, Jachna BR. Care of the clinician after an adverse event. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2015;24:54–63.

- Schwappach DL, Boluarte TA, The emotional impact of medical error involvement on physicians: a call for leadership and organisational accountability. Swiss Med WKly. 2009;139(1-2):9-15.

- White AA.The attitudes and experiences of trainees regarding disclosing medical errors to patients. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):250-6.

- Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, et al. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:467-476.

- Pratt S, Kenny L, Scott SC, Wu AW. How to Develop a Second Victim Support Program: A Toolkit for Health Care Organizations. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(5):235-40, 193..

- Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW. The natural history of recovery for the health care provider ‘second victim’ after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(5):325-330.

- Shapiro J, Galowitz P. Peer Support for Clinicians: A Programmatic Approach. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1200-4.

- Scott SD, McCoig MM. Care at the point of impact: Insights into the second-victim experience. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2016;35(4):6-13.

- Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Hahn-Cover K, Epperly KM, Phillips EC, Hall LW. Caring for our own: deploying a systemwide second victim rapid response team. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(5):233-40.

- Boysen P. Just culture: a foundation for balanced accountability and patient safety. Ochsner J. 2013;13(3):400–406.