A 24-year-old male with a past medical history of cannabis use presented to the emergency department 4 times in a short period with progressive neurological symptoms.

On his first presentation, the patient reported a 4-day history of intermittent and migratory numbness of the feet and hands. He endorsed recovering from a brief respiratory illness a few weeks prior, as well as extensive recreational cannabis use. He denied a history of intravenous drug use. Serious neurologic disease, namely Guillain-Barré, was considered in the differential diagnosis. However, his physical exam was largely reassuring. He was noted to have mild patellar hyperreflexia bilaterally and a normal (downgoing) Babinski sign. Screening labs (CBC, BMP, hepatic panel) were normal. His presentation was ultimately attributed to his cannabis use, and the patient was advised to reduce his cannabis use and to follow up with Neurology for nerve conduction studies.

Two weeks later, the patient returned to the ED with a complaint of worsening numbness in his bilateral hands and feet, now described as constant. He also reported significant anxiety and requested medication for this. He described continued marijuana use as well as newly reported recreational nitrous oxide use. He admitted this had transpired prior to his first visit, but he had not felt comfortable disclosing that information. On this visit, the patient’s neurologic exam was noted to be normal, although reflexes were not specifically documented. Labs were again unremarkable. He was encouraged to utilize his Neurology referral. He was discharged with a short course of diazepam for anxiety and instructions on mindfulness and breathing exercises.

The patient re-presented 5 days later with a chief complaint of numbness and weakness. Unfortunately, due to high patient volumes and boarding, he did not receive a full evaluation before leaving the emergency department, but he did undergo a medical screening exam. He reported that he was now having weakness and difficulty walking, which he attributed to complete loss of sensation in his feet. The patient was concerned for vitamin B12 deficiency based on his internet searching and requested a B12 shot. The patient did not have a physical exam documented on this visit (the facility's medical screening note template did not include physical exam findings). The patient was given a vitamin B12 shot, per his request.

On the patient's fourth emergency department encounter, 23 days after his initial presentation, he returned in a wheelchair with chief complaints of dizziness, decreased sensation, and muscle tightness. He stated that he "didn't know where his feet were" and had been utilizing a wheelchair for a few days due to his inability to ambulate. The patient was more forthcoming on this visit and stated that his symptoms actually began 1 month prior, after a night of heavy nitrous oxide use. Physical exam was remarkable for increased tone in the distal extremities, loss of proprioception and vibratory sense from C8 downward, positive Hoffman sign, 10-12 beat clonus at the ankles bilaterally, upper and lower extremity hyperreflexia, and somewhat diminished pinprick sensation on the face. A broad workup was initiated, including MRIs of the cervical and thoracic spine. These demonstrated findings of subacute combined degeneration of the dorsal column through a significant portion of both the cervical and thoracic spinal cord, raising concern for acute myelopathy related to nitrous oxide toxicity. Neurology was consulted from the emergency department and recommended admission to the hospital for further workup.

Image 1. MRI of cervical spine

Image 2. MRI of thoracic spine

Case Management and Resolution

During the inpatient course of our patient, additional history regarding his nitrous oxide use was obtained. He reported using nitrous oxide on a daily basis for approximately 2 weeks prior to symptom onset, and stopped his use upon noticing his initial symptoms of extremity numbness.

Neurology documented even more extensive neurologic damage on their exam, including diminished sensation distal to the level of the clavicles, spastic tone in upper and lower extremities, spastic and wide-based gait, and intermittent urinary retention requiring catheterization.

During his hospital stay, the patient received daily cyanocobalamin injections but saw no significant neurological improvement. He was ultimately discharged from the hospital to inpatient rehabilitation for treatment of substance use disorder as well as for extensive physical/occupational therapy. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Differential Diagnosis Discussion

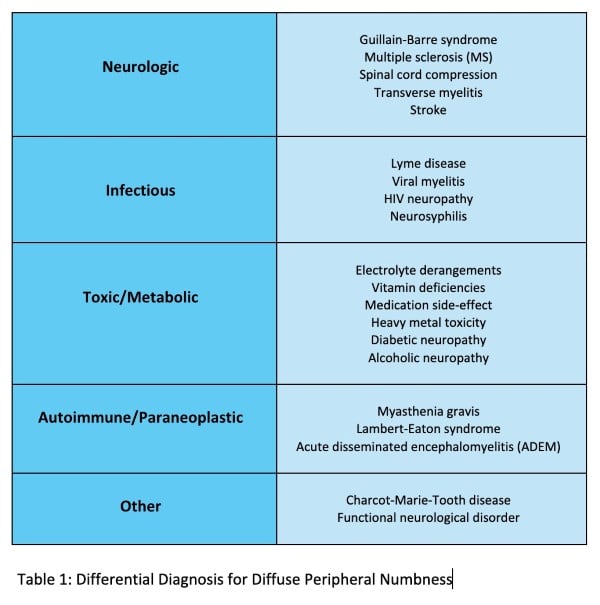

The differential diagnosis for diffuse peripheral numbness, an outline for which is depicted in Table 1, is quite broad. If an underlying neuropathy is suspected, one of the most important distinctions to make is whether symptoms originate from the central or peripheral nervous system.

When motor symptoms are present, findings on physical exam are particularly useful. The presence of hyperreflexia, spasticity, and an upgoing (abnormal) Babinski, which were present in this patient, imply involvement of the brain and/or spinal cord. Hyporeflexia, flaccidity, and a downgoing (normal) Babinski are typical of a peripheral nervous system issue.1 Both central and peripheral causes can be life-threatening. However, making the proper diagnosis will often rely on different modalities. When a central cause (MS, ADEM, transverse myelitis, subacute combined degeneration, etc.) is suspected, imaging, particularly MRI of the brain and/or spinal cord, is useful and can often be diagnostic.

For this patient, the differential diagnosis initially focused on marijuana intoxication and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Acute marijuana intoxication is associated with incoordination and chronic use has been shown to cause anxiety and hyperreflexia, though the extent of his physical exam findings, especially on later presentations, would be inconsistent with this.2 Although the time-course of his neurological symptoms after respiratory infection would have been consistent Guillain-Barré syndrome, the hyperreflexia would have been unusual.

Guillain-Barré typically presents with areflexia or hyporeflexia; only rare cases of axonal Guillain-Barré syndrome are known to manifest with hyperreflexia, and these cases are typically preceded by a gastrointestinal infection.3 After the second visit, when the patient admitted to using recreational nitrous oxide, the differential shifted toward this toxicity. However, the patient did not receive a complete workup for the suspected cause of symptoms until his neurologic deficits had progressed to significant dysfunction and inability to perform activities of daily living.

Nitrous Oxide Toxicity

Recreational abuse of nitrous oxide, colloquially known as laughing gas or whippets, is increasing in prevalence due to its widespread availability, in both retail stores and online, and is most often seen in adolescent or young adult males.4 There are multiple mechanisms by which large doses or chronic exposure to nitrous oxide can produce toxicity. One that is well understood and potentially treatable is functional vitamin B12 deficiency.4 Nitrous oxide inactivates cobalamin (vitamin B12), which leads to downstream irreversible blocking of methionine synthase and consequential lack of production of metabolites needed for DNA synthesis and myelin production.5 This results in demyelination within the central and peripheral nervous systems. Clinically, this often manifests as severe neurologic complications including subacute combined degeneration (SCAD) and myelopathy. These often present just as this patient did—with paresthesia, gait instability, and weakness.4 Laboratory work-up may elucidate low serum levels of cyanocobalamin, though it is important to note that patients can have normal levels.6,7 If left untreated, or if not treated in a timely manner, neurologic deficits are often irreversible.4

Currently, there is no defined treatment recommendation for individuals with nitrous toxicity, but the generally accepted plan is scheduled cyanocobalamin injections, as were administered to this patient.4,6–8 Although this patient did not show improvement in an inpatient setting, other cases in the literature have demonstrated significant decrease in symptoms and occasionally full recovery with early identification, cessation of use, and aggressive B12 treatment.7,8 Therefore, obtaining a thorough patient history and maintaining suspicion for nitrous oxide abuse is crucial for improved patient outcomes.

Nitrous oxide toxicity is difficult to diagnose due to variable reliability of patient histories and ambiguity of presentation, so this condition often goes unrecognized. Half of individuals in the United States aged 12 and older have used illicit drugs at least once.9 Despite the significant prevalence of substance use in our population, healthcare workers have been found to exhibit implicit biases or negative attitudes toward caring for individuals who endorse substance use, as well as a lack of trust in the reliability of this patient population.10,11 In a setting that is designed to care for emergently ill individuals, it is possible that providers may have approached this patient’s encounters with some implicit biases regarding his reported marijuana use, and subsequently easily dismissed his concerns especially given his reassuring physical exam on the first three visits.

Another salient aspect of this case is the number of ED presentations this patient had before receiving an accurate diagnosis and proper treatment. A large analysis of short-term return visits to the emergency department has outlined multiple categories that drive these visits, including factors related to the patient, provider errors in diagnosis or management, healthcare system issues, and factors related to the underlying illness.12 All of these factors were at play in this patient’s case. Non-disclosure of nitrous use at his initial visit, cognitive bias of providers, high boarding resulting in the patient leaving before a complete evaluation was performed on his third visit, and ultimate progression of his symptoms during this timeframe likely all contributed to the number of ED visits preceding his diagnosis and admission. Other studies have demonstrated that patients who return to the emergency department for the same complaint are at increased risk of adverse outcomes, suggesting that a broadened work-up and closer consideration of admission may have been warranted on earlier return visits.13

Sources

- Zayia LC, Tadi P. Neuroanatomy, Motor Neuron. StatPearls Publishing. 2023.

- Caplan RA, Zuflacht JP, Barash JA, Fehnel CR. Neurotoxicology Syndromes Associated with Drugs of Abuse. Neurol Clin. 2020;38(4):983-996.

- Uncini A, Notturno F, Kuwabara S. Hyper-reflexia in Guillain-Barré syndrome: systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(3):278-284.

- Xiang Y, Li L, Ma X, et al. Recreational Nitrous Oxide Abuse: Prevalence, Neurotoxicity, and Treatment. Neurotox Res. 2021;39(3):975-985.

- Weimann J. Toxicity of nitrous oxide. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17(1):47-61.

- Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: A systematic review of the case literature: Toxic Effects of Nitrous Oxide Abuse. Am J Addict. 2016;25(5):358-369.

- Birch MS, Samones EJ, Phan T, Guptill M. A Case Report of Nitrous Oxide-induced Myelopathy: An Unusual Cause of Weakness in an Emergency Department. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2023;7(3).

- Hsu CK, Chen YQ, Lung VZ, His SC, Lo HC, Shyu HY. Myelopathy and polyneuropathy caused by nitrous oxide toxicity: A case report. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(6):1016.e3-1016.e6.

- National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics. Drug Abuse Statistics. Accessed March 27, 2025.

- Mendiola CK, Galetto G, Fingerhood M. An Exploration of Emergency Physicians’ Attitudes Toward Patients With Substance Use Disorder. J Addict Med. 2018;12(2):132-135.

- Van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, Van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35.

- Montoy JC, Tamayo-Sarver J, Miller GA, Baer AE, Peabody CR. Predicting Emergency Department “Bouncebacks”: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(6):865-874.

- Hutchinson CL, Curtis K, McCloughen A, Qian S, Yu P, Fethney J. Identifying return visits to the Emergency Department: A multi-centre study. Australas Emerg Care. 2021;24(1):34-42.