You are working in the emergency department on a pleasant Sunday afternoon when the paramedics wheel in an 85-year-old gentleman who has been having diffuse abdominal pain for 7 days. His daughter came to visit this afternoon and noticed that her father was in pain, so she called the ambulance. He doesn't feel like he needs to be here and would prefer to go home. He does admit to having diffuse abdominal pain for the past week, but denies any associated symptoms. He takes four pills but he's not sure what they are, one for high blood pressure and one for cholesterol, maybe. He usually gets his care at Veterans Affairs, and therefore you have no records in your system. On exam, he is well-appearing and afebrile with mild tenderness to palpation of the right lower quadrant. His workup is remarkable for a white blood cell count of 14,000 and pyuria.

Should you treat this patient for a UTI and call it a day? What is your next step?

Background

Geriatric patients, generally defined as persons age 65 and older, comprise a specific, vulnerable, and ever-growing population within the emergency department. Frequently, care of these patients requires modification of existing diagnostic and treatment paradigms.

In particular, older patients presenting with abdominal pain can be challenging for a few reasons. First, the physical exam may be falsely reassuring. For example, older patients with infections do not necessarily have fevers (Figure 1).1

Even in the face of a serious intra-abdominal pathology, they are equally as likely to be normothermic or hypothermic as hyperthermic.2

Second, medications such as beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers may mask tachycardia.

Third, peritoneal symptoms are much less common, possibly because aging changes the way elderly patients experience pain.3 In one study of older patients, 80% of geriatric patients with perforated peptic ulcers did not have peritonitis.4

Finally, older patients often have multiple comorbidities, which can complicate diagnostic processes.

Diagnostic Considerations

It may be helpful to think about a few idiosyncratic ways in which intra-abdominal pathology presents differently in older patients.

- Appendicitis

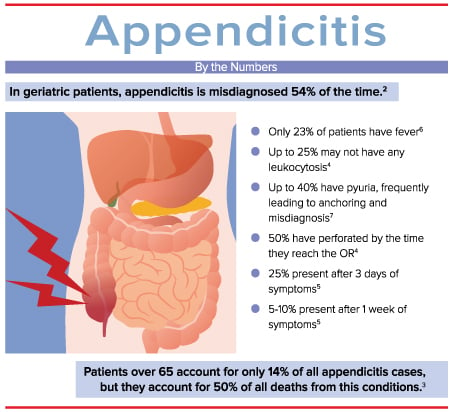

Appendicitis should be on your differential for geriatric patients presenting with abdominal pain, since it is the most commonly missed diagnosis in older patients and carries high morbidity and mortality.

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA)

The most common diagnosis in missed ruptured AAA is renal colic.6 Recall that a AAA can rupture into the retroperitoneum and tamponade, resulting in normotension. In addition, a AAA can irritate the ureter and cause microscopic hematuria. The classic combination of flank pain and hematuria in older patients should prompt consideration of AAA in addition to nephrolithiasis. In general, a new diagnosis of “kidney stones” in a patient older than age 50 should trigger imaging of the aorta before a patient is discharged from the hospital.

- Mesenteric Ischemia

Another rare condition that can be challenging to diagnose in this population is mesenteric ischemia.7 Perhaps not intuitively, the most common diagnosis in missed mesenteric ischemia is gastroenteritis. As bowel becomes ischemic, “gut emptying” can occur, causing nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. As with younger patients, consider investigating serious pathology before anchoring on a diagnosis of viral infection. Likewise, an elevated lipase or amylase should not immediately point towards the direction of pancreatitis, as these lab values may also be elevated in mesenteric ischemia.

Atrial fibrillation is, of course, a risk factor for mesenteric ischemia, but so are other disorders leading to left ventricular stasis, such as ventricular aneurysm from a prior myocardial infarction. Although mesenteric ischemia can be challenging to diagnose, the high mortality rate should prompt thoughtful consideration in any older patient presenting with abdominal pain.

- Peptic Ulcer Disease

While peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is associated with less morbidity than mesenteric ischemia, it is also far too often missed in older patients. In this patient population, the first presentation of PUD is often an acute complication of the disease, such as perforation.8 Serious pathology, including peritonitis, can have a relatively benign exam. As previously stated, in one study, only 20% of geriatric patients with perforated peptic ulcers actually had peritonitis.4 Moreover, plain films are often non-diagnostic, as demonstrated in one study that found a whopping 39% of patients with perforated peptic ulcer without evidence of pneumoperitoneum on plain films.9 CT is therefore the imaging modality of choice.

You decide to order a computed tomography (CT) scan of your patient's abdomen and pelvis, which reveals acute appendicitis. Surgery is consulted and the patient is added on for the operating room.

Conclusion

In general, the approach to abdominal pain in geriatric patients requires careful consideration of the physiologic changes associated with aging, differences in pain perception, and the confounding effects of medical comorbidities and polypharmacy.

Want to Know More?

If interested in learning more about geriatric emergency medicine, please visit www.gempodcast.com, a blog/podcast devoted to older adult emergencies. Another great resource is www.pogoe.org, which is a free collection of expert-contributed geriatrics educational content for both educator and learners. We would also encourage you to join SAEM's Academy of Geriatric Emergency Medicine, as well as ACEP's Geriatrics Section at www.acep.org/geriatricsection.

References

- Katz ED, Carpenter CR. Fever and immune function in the elderly: In Meldon SW, Ma OJ, Woolard R, ed. Geriatric Emergency Medicine, New York, 2004, McGraw-Hill, Figure 9-1, p.59.

- Kauvar DR. The geriatric acute abdomen. Clin Geriatr Med. 1993;9(3):547-558.

- Fenyö G. Diagnostic problems of acute abdominal diseases in the aged. Acta Chir Scand. 1974;140(5):396-405.

- Martinez JP, Mattu A. Abdominal pain in the elderly. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006;24(2):371-388, vii.

- Fenyö G. Acute abdominal disease in the elderly: experience from two series in Stockholm. Am J Surg. 1982;143(6):751-754.

- Johansen K, Kohler TR, Nicholls SC, Zierler RE, Clowes AW, Kazmers A. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: the Harborview experience. J Vasc Surg. 1991;13(2):240-245; discussion 245-247.

- Cudnik MT, Darbha S, Jones J, Macedo J, Stockton SW, Hiestand BC. The diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(11):1087-1100.

- Caesar R. Dangerous complaints: the acute geriatric abdomen. Emerg Med Rep. 1994;94:191-202.

- McNamara R, Dean AJ. Approach to acute abdominal pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011;29(2):159-173, vii.

Additional Resources

Dickinson M, Leo MM; Gastrointestinal emergencies in the elderly. In: Geriatric Emergency Medicine Principles and Practice by Kahn JH, Magauran BG, Olshaker JS (Eds), Cambridge Medicine. 2014;207-218.

Magidson PD, Martinez JP. Abdominal Pain in the Geriatric Patient. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2016;34:559-574.

Tyler, Kennedy; Acute abdominal pain in the elderly: surgical causes. In: Geriatric Emergencies: A discussion-based review by Mattu A, Grossman SA, Rosen PL et al (Eds), Wiley-Blackwell 2016;83-98.