A 41-year-old male who is an incarcerated inmate presents to the emergency department via EMS. He has a past medical history of anxiety and unspecified seizure disorder.

The patient states he was walking to his room in the prison when he was attacked from behind and stabbed with a blade. EMS adds the blade was 8” in length. The attack caused the patient to fall to the ground, without head-strike or loss of consciousness. The patient reports an inability to move his right leg, along with diminished sensation in his left leg.

Initial vital signs were unremarkable. Trauma exam was unremarkable except for an approximately 2 cm long penetrating wound in the L paraspinal thoracic region of the back. The patient had a total inability to move his right leg and to detect pain sensation in the left leg, tested by pricking the medial, lateral, and dorsal aspects of the foot with an IV catheter. He had diminished temperature sensation to the lateral left foot, which was tested by holding an ice cube against the skin.

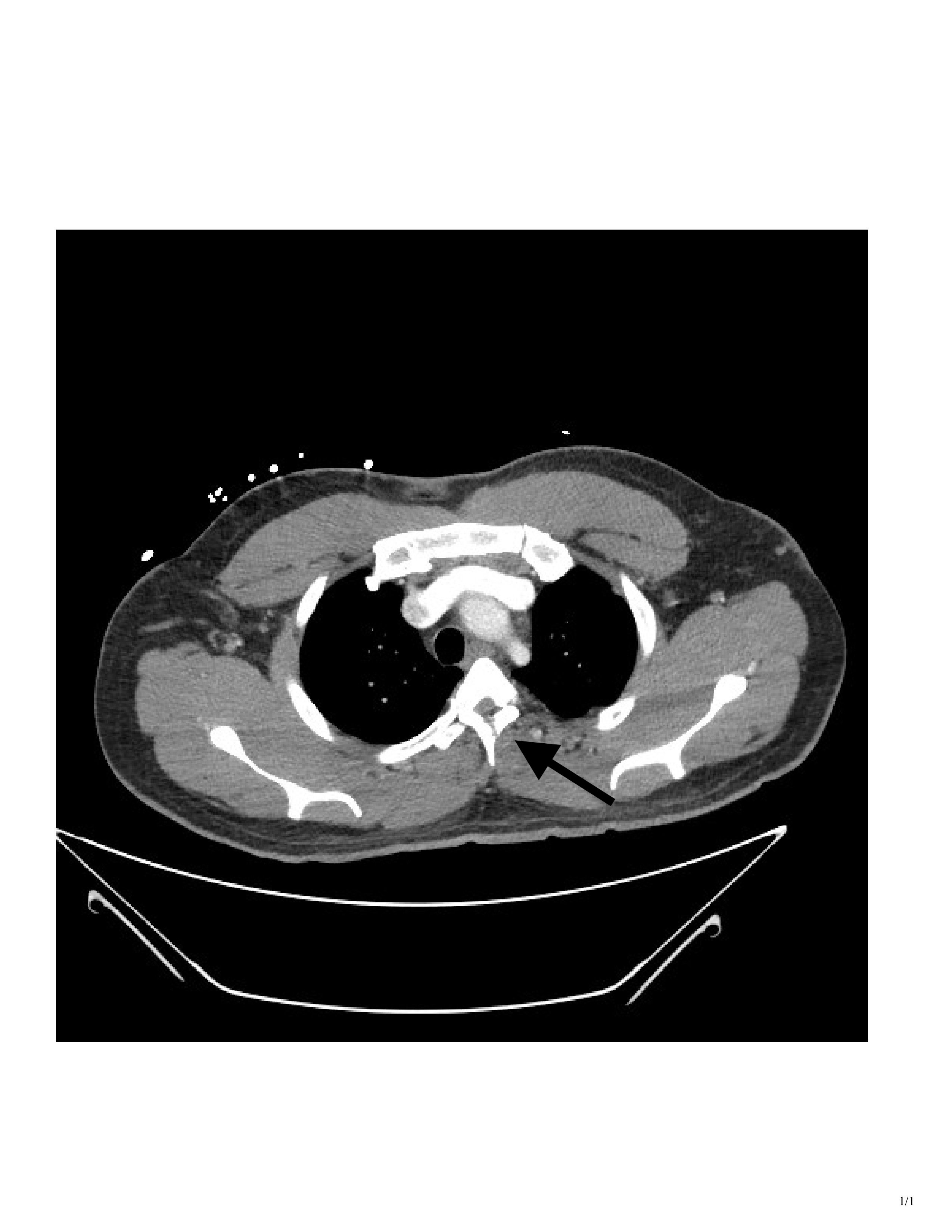

CT imaging showed a T3 spinous process fracture raising concern for intracanal blood products and possible cord injury. MRI later that night confirmed cord contusion with possible injury to the right hemi cord, and dorsal epidural hematoma extending from T2 to T10.

Incomplete spinal cord injuries are often taught in medical school, as they provide a means of instructing neural anatomy. These injury patterns are less commonly seen in clinical practice, but when they do present, it is worth taking the time to review the relevant pathways.

Although this patient’s penetrating wound entered on the left paraspinal region and fractured through the spinous process on the left, it injured the cord on the right side. Given that only one side of the patient’s cord was injured, the deficits depended on where the different pathways were injured in relation to their areas of decussation (crossing over).

The lateral corticospinal tract controls voluntary musculoskeletal movement, and the tract begins in the frontoparietal part of the brain, before decussating in the medulla and descending to the appropriate level, synapsing with neurons at the anterior horn cells. By the time the axons enter the spinal cord, they are running along the same side as the target muscle, which is why our patient with a right cord hemi-section had loss of motor function in the right leg.

The spinothalamic tract controls pain and temperature sensation, and the tract decussates two spinal cord levels above its point of entry. Because of its early decussation, the pain and temperature deficits are experienced on the opposite side, which is why our patient could not feel an ice cube or an IV catheter of his left leg.

The dorsal column controls vibratory sensation and 2-point discrimination. The neurons enter the spinal cord through the dorsal root ganglia and ascend the cord on the ipsilateral side, ultimately decussating in the medulla. Classically, patients with Brown-Séquard Syndrome would have ipsilateral deficits of vibratory sense and 2-point discrimination. Unfortunately, a tuning fork was not immediately available to assess for vibratory perception, and we failed to assess for 2-point discrimination, which may have been accomplished by using a standard paper clip.

At the time of presentation, we knew the patient displayed clinical signs of Brown-Séquard, and the CT showed injury on the right side of the cord. What was unclear at the time was whether the patient had a true hemi-section of the spinal cord, leading to permanent disability, or if he was instead suffering from a transitory spinal shock due to swelling and hematoma.

An MRI obtained the next day confirmed right-sided spinal cord hemi-section, as well as associated cord contusion and epidural hematoma. Additionally, when the patient was discharged from the Shock Trauma ICU several days later, he was still exhibiting the same neurological deficits. The patient was discharged directly to a rehabilitation center, where occupational and physical therapists were expected to help him maximize his recovery and learn to live with his new deficits.

References

- Brown-Sequard Syndrome. Physiopedia. Accessed Dec. 3, 2025.

- Al-Chalabi M, Reddy V, Alsalman I. Neuroanatomy, Posterior Column (Dorsal Column). StatPearls. 2020.

- Al-Chalabi M, Reddy V, Gupta S. Neuroanatomy, Spinothalamic Tract. StatPearls. 2023 Aug 14.

- Natali AL, Reddy V, Bordoni B. Neuroanatomy, Corticospinal Cord Tract. StatPearls. 2020, updated 2023 Aug 14.

- Shams S, Arain A. Brown Sequard Syndrome. StatPearls. 2020, updated 2024 Feb 27.