Clinical Case

A 39-year-old female presents with acute right lower abdominal pain that awoke her from sleep. Her only medical history involves progesterone use, prescribed from a fertility clinic. She initially appears nontoxic and has normal vital signs, though does have moderate pain in her right lower quadrant. An immediate transvaginal ultrasound reveals no evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy, though both ovaries are markedly enlarged, and there is scant free fluid in the pelvis. In a matter of minutes, the patient becomes hypotensive and tachycardic, and bedside abdominal ultrasound shows a large quantity of intraperitoneal free fluid. Soon thereafter her hemoglobin returns at 6.2g/dL, down from a baseline of 12.8. She is aggressively transfused and transferred to the OR with a presumptive diagnosis of ruptured ectopic pregnancy. There, laparoscopy reveals a ruptured and torsed right ovary measuring 14cm x 12cm x 10cm. There is no evidence of ectopic pregnancy. She is then diagnosed with acute hemorrhagic shock secondary to her torsed, hemorrhagic ovary, caused by ovarian hyperstimulation. The patient ultimately does well, and later goes on to support a viable twin gestation.

Discussion

In the United States, 6.7 million women are diagnosed with impaired fecundity.1 With advances in reproductive technology and wider insurance coverage, more than 175,000 cycles of assisted reproductive technology (ART) are performed on an annual basis.2 Whereas the use of in vitro fertilization in the United States is recorded in a national registry, the use of non-ART ovulation stimulation is not reported, and specific data is not available. By one estimate, the mean percentage of all U.S. births conceived with non-ART ovulation stimulation was 4.62% in 2005 (95% CI 2.8%–7.1% corresponding to 114,782–292,713 infants yearly).3 Approximately 40.5 million women are currently seeking infertility treatment globally.4 As these numbers are thought to be increasing, these patients are more likely to seek care in a local emergency department. Emergency physicians, therefore, need to have knowledge of both the common and the life-threatening complications of fertility treatment, including both ART and non-ART ovulation stimulation.

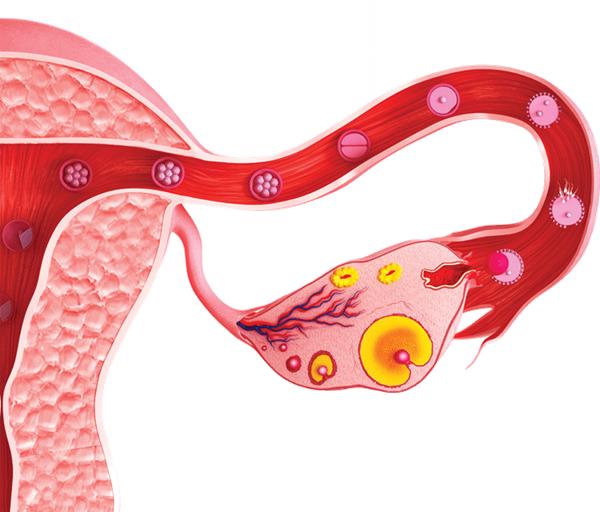

In normal ovulation, a dominant follicle is triggered to ovulate by a surge in luteinizing hormone (LH), while the few non-dominant follicles undergo apoptosis and are absorbed into the ovary. The dominant follicle matures into a corpus luteum made of granulosa cells, which secrete estrogen and progesterone, in addition to smaller amounts of vasoactive proteins. Ovulation stimulation hinges upon the hormonal manipulation of ovarian follicles using a combination of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and antagonists, as well as hCG timed to maximize oocyte formation.

The physiological changes induced by these hormonal interventions may have complications. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, ovarian torsion, ectopic and heterotopic pregnancy, ovarian hemorrhage, ovarian cyst rupture, and infection secondary to oocyte harvest have all been reported in patients who have undergone ART. Each of these entities usually presents as lower abdominal pain, nausea, and bloating with free fluid in the abdomen visualized on ultrasound. It is important, but challenging, to distinguish between these diagnoses.

Ectopic pregnancy is commonly considered among the high-risk diagnoses that may lead to abdominal pain in pregnancy. This potentially life-threatening diagnosis occurs in 2.3% of pregnancies from ART.5 Additionally, 1% are heterotopic pregnancies: a viable intrauterine pregnancy in conjunction with a concurrent ectopic pregnancy.6 The presentation of the case above was suggestive of ectopic pregnancy. While ectopic pregnancy is prevalent in this population, additional etiologies must be considered in the fertility patient.

Ovarian stimulation – the medical induction of ovulation – contributed to the patient's presentation in our case. However, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) – the constellation of symptoms or medical side effects directly from ovarian stimulation therapy – should also be in the differential diagnosis. OHSS exists on a spectrum ranging from mild to life-threatening symptoms. Mild presentations include abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, and bloating due to a small amount of ascites from follicle rupture after ovulation, and are usually managed as outpatients in conjunction with their fertility specialist. OHSS becomes severe when fluid rapidly shifts into the peritoneum, resulting in weight gain and massive ascites. These fluid shifts can progress to oliguria, hemodynamic instability, and respiratory compromise. If not appropriately and aggressively managed, these patients can develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), hepatic failure, renal failure, hyperviscosity, thromboembolism, or ovarian rupture and hemorrhage.9,10

Hyperstimulated ovaries may also become engorged and prone to torsion. The torsion risk may be further increased when OHSS has developed, particularly when the patient is pregnant.10,11 As with ectopic pregnancy, this represents a surgical emergency with implications for future fertility and the viability of the current pregnancy.

Differentiating between these potential etiologies is challenging. Abdominal discomfort or a bloating sensation could result from OHSS, ectopic pregnancy (including heterotopic), or torsion. Intra-abdominal free fluid could either be blood or ascites. OHSS produces an engorged ovary with abundant follicles, and the appearance of an ectopic pregnancy can be difficult to distinguish from the multiple complex ovarian cysts of OHSS. Patients presenting with these diagnoses often have pregnancies that are too early to detect by ultrasound at all, further obscuring the diagnosis of ectopic or heterotopic pregnancy. There are multiple case reports of heterotopic pregnancy with hemoperitoneum presenting as OHSS, for example.10

Summary

Ovarian stimulation is used therapeutically to treat infertility. It is associated with multiple complications, notably ectopic pregnancy, OHSS, torsion, and ovarian hemorrhage. The possibility of multiple concurrent diagnoses should prompt a broad-based investigation and early consultation with the patient's gynecologist and reproductive endocrinologist, but timely recognition and intervention hinge on the actions of the emergency medical provider.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. FastStats. Infertility. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/fertile.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART). National ART Success Rates. 2012 National Summary. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/art/Apps/NationalSummaryReport.aspx.

- Schieve LA, Devine O, Boyle CA, et al. Estimation of the Contribution of Nonassisted Reproductive Technology Ovulation Stimulation Fertility Treatments to US Singleton and Multiple Births. Am J Epidemiol. 2009 Dec 1;170(11):1396-407.

- Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, et al. New debate: international estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod. 2007; 22: 1506–1512.

- Jee BC, Suh CS, Kim SH. Ectopic pregnancy rates after frozen versus fresh embryo transfer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68(1):53-7.

- Molloy D, Deambrosis W, Keeping D, et al. Multiple-sited (heterotopic) pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and gamete intrafallopian transfer. Fertil Steril. 1990 Jun;53(6):1068-71.

- Vloeberghs V, Peeraer K, Pexsters A, D'Hooghe T. Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome and Complications of ART. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009 Oct;23(5):691-709.

- The Practice Committee of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008 Nov;90(5 Suppl):S188-93.

- Fisher SL, Massie JA, Blumenfeld YJ, Lathi RB. Sextuplet Heterotopic Pregnancy Presenting as Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome and Hemoperitoneum. Fertil Steril. 2011 Jun;95(7):2431.e1-3.

- Gorkemli H, Camus M, Clasen K. Adnexal torsion after gonadotrophin ovulation induction for IVF of ICSI and its conservative treatment. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2002; 267: 4-6.

- Mashiach S, Bider D, Moran O, et al. Adnexal torsion of hyperstimulated ovaries in pregnancies after gonadotropin therapy. Fertil Steril. 1990; 53(1): 76–80.