Intussusception is a common pathology seen in pediatric emergency rooms across the country. In fact, it is the number one cause of bowel obstruction in children under 3 years of age,1,2 and the second most common cause of acute abdomen in pediatric populations.3 Children between the ages of 2 months and 2 years are most susceptible to intussusception, with the majority of cases occurring between 5 and 9 months of age.3 Intussusception is the result of invagination of a segment of bowel, the intussusceptum, into a more distal segment of bowel, the intussuscipiens.1,3 The most common type of intussusception is ileocolic followed by Ileo-ileo. In ileocolic cases, the terminal ileum telescopes into the ascending colon through the ileocecal valve.4

Etiology

The most common cause of intussusception is idiopathic; however, many cases are thought to be due to a pathological lead point within the intestine.1-5 The etiology of lead points vary depending on age.

|

Under 3 years of age 1,2,6 |

Peyer patch hyperplasia in the distal ileum typically following a viral gastroenteritis. |

|

Above 3 years of age 1,6 |

Common lead points identified are: Meckel’s diverticulum Intestinal duplications and polyps Lymphoma and abdominal masses Henoch-Schonlein Purpura Peutz Jeghers Syndrome Familial Polyposis Cystic Fibrosis

|

Presentation

A child with intussusception is likely to be irritable, inconsolable, and presents with a wide variety of symptoms. The classic clinical triad of intussusception includes 1) intermittent, episodic abdominal pain, 2) a sausage-shaped abdominal mass on the right side of the abdomen, and 3) red, currant jelly stool. However, these symptoms do not occur in the majority of cases.3-5,7 When examining the child, look for these signs as well as other commonly seen symptoms such as the patient drawing up his or her legs while in pain, listless behavior between episodes of pain, and emesis. Oftentimes, patients will have a glazed look in their eyes as though the “lights are on but nobody's home.” It is important to note that if currant jelly stools are seen, this is indicative of a longer disease process as it is related to vascular injury and bowel wall ischemia. If left untreated, this may lead to infarction and perforation of the bowel.1

Diagnosis

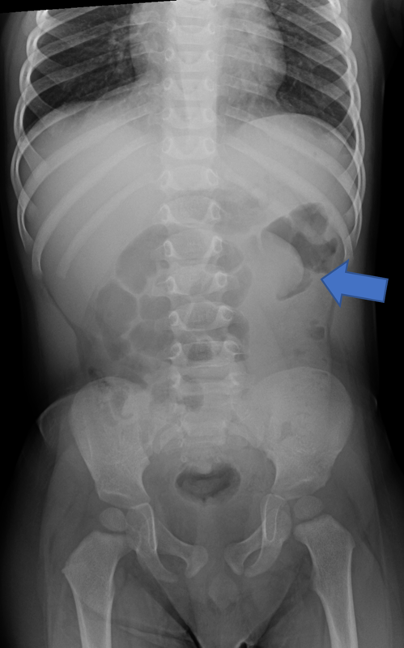

Diagnosis of intussusception is made primarily through imaging, in the setting of the above clinical presentation. Often abdominal radiographs are obtained as the first image in the emergency department setting. Radiographs are neither sensitive nor specific, but are useful for identification of an obstructive bowel gas pattern and the presence of abdominal free air.3,4 The primary signs to look for when examining an abdominal radiograph are the “crescent sign,” which is formed by bowel gas delineating the vertex of the intussusception and a lack of bowel gas in the ascending colon (Fig. 1).3 Ultrasound (US) is a highly sensitive modality for the identification of intussusception and is the preferred means of diagnosis in pediatric populations.1,3,4

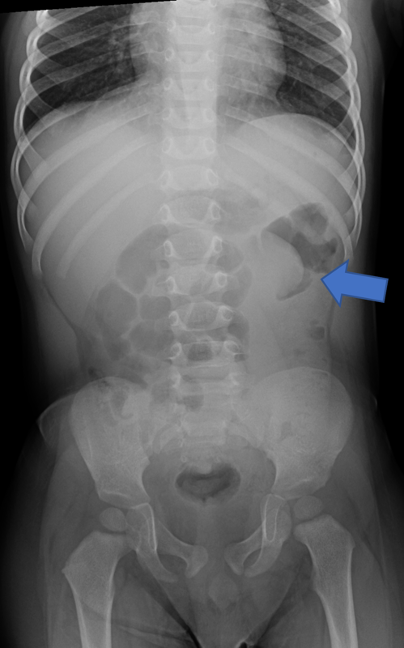

(Figure 1: left) (Figure 2: Right)

Figure 1: Supine abdominal radiograph. A crescent sign is demonstrated near the splenic flexure. There is mild gaseous distention of the proximal bowel, with paucity of gas in the left abdomen.

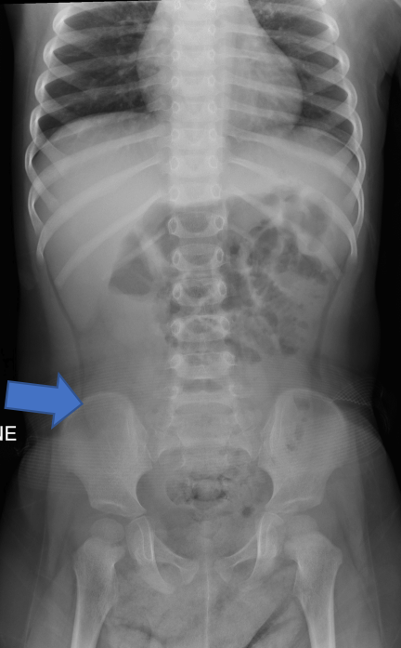

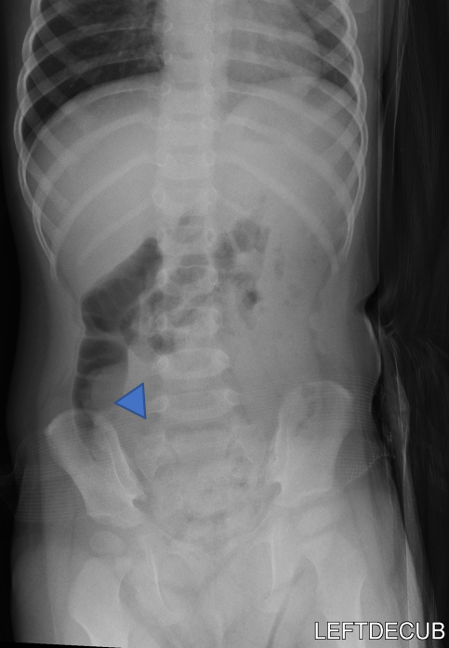

(Figure 3)

Figure 3: Supine and left decubitus abdomen radiographs.

- There is paucity of gas in the ascending colon (arrow).

- The ascending colon is partially air-filled on the left decubitus view, with a soft tissue density in the cecum (arrowhead). This soft tissue density is delineated by air, resembles the crescent sign. No evidence of peritoneal free air.

Technique

Probe: High-frequency linear transducer (5-12 MHz). A curvilinear probe may be substituted in larger or older children to increase depth of view.

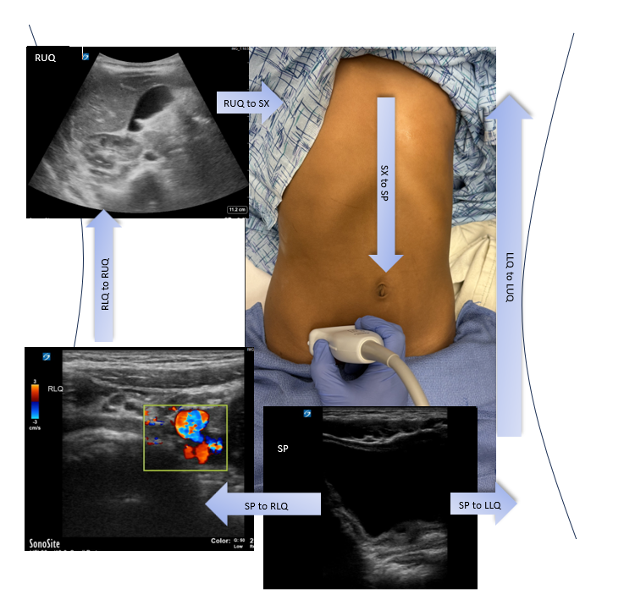

Patient is positioned supine and the abdomen is scanned systematically in both transverse and longitudinal planes. Employing the lawnmower technique aids to ensure all areas of the abdomen are scanned (Fig. 3). Gentle graded compression is applied to displace bowel gas.

Intussisception appears as a non-compressible, target-shaped mass with concentric echogenic and hypoechoic rings on the transverse view and as a “pseudokidney” or “stack of pancakes” on the longitudinal views (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 a,b,c).1,3,4 The important characteristic appearance on transverse scan is the presence of the central/eccentric and hyperechoic mesenteric fat, that is pulled with vessels and lymph nodes into the intussusception by the intussusceptum; which differentiates from other entities, such as bowel hematoma, stool, bowel wall edema, mass, or even a psoas muscle.9 Doppler ultrasonography can also be useful to detect and evaluate blood flow. The absence of flow is a sign that surgical reduction may be necessary.4

(Figure 4)

Figure 4: Lawnmower Method

Identify bladder in Suprapubic (SP) View, start moving the probe laterally to the Right Lower Quadrant (RLQ) and identify iliac vessels. Keep moving the probe laterally until you identify the iliac crest. The ileocecum is cephalud to the iliac crest. Then move cephalically toward the Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ). Rotate probe with probe marker facing up and advance probe medially to the Subxiphoid area (SP). Rotate probe again with probe marker facing right and advance probe caudally though the center of the abdomen, stopping after you obtain the SP view again. Then progress to capture the Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ) by moving laterally, and finally by obtaining the Left Upper Quadrant (LUQ) by advancing probe cephalically.

(Figure 5)

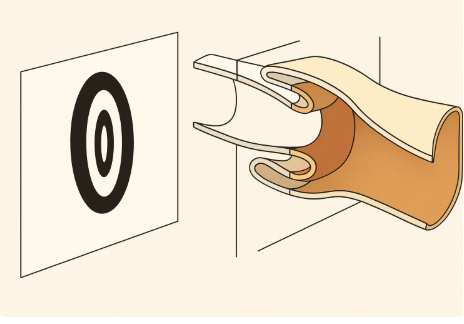

Figure 5: Illustration depicting the pathophysiology of intussusception.

On the right, a cross-sectional view of the bowel demonstrates telescoping of the proximal segment (intussusceptum) into the distal segment (intussuscipiens), resulting in the characteristic “target sign” appearance shown on the left. The layers of the bowel wall—mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis—are represented in distinct shades to emphasize the concentric rings visualized on ultrasound. This diagram highlights the mechanical invagination responsible for bowel obstruction and vascular compromise in intussusception.

(Figure 6a: Left) (Figure 6b: Center) (Figure 6c: Right)

Figure 6a-6c. Right lower quadrant ultrasound, transverse (a) and longitudinal views (b). (c) Layered 3.4 cm appearance mass is identified in the right lower quadrant, interposed hypo/hyper echogenic layers, with central hyperechoic mesentery fat, representing the intussusceptum (arrow).

Treatment

The primary means of reduction is through air enema or hydrostatic enema with saline or a water soluble contrast material.3,4 Studies have shown that air enema has increased success with comparable rates of perforation,3,4,8 and is an easier and shorter procedure.3,4 Therefore, air enema is the modality of choice; however, this varies by institution. The contraindications to enema reduction are shock, peritonitis, and/or radiographic evidence of perforation with free air.1,3 A patient should be referred to the Surgery department if they have any of these symptoms or if enema reduction is unsuccessful.1

Of note, there are multiple factors that have been found to decrease the success rate of enema reduction; such as younger age, rectal bleeding, intestinal obstruction, or longer duration of signs and symptoms. However, successful reduction can be achieved in the presence of any of these factors and, consequently, none of them prevent an attempted enema reduction if the patient is well hydrated and clinically stable.10 Therefore, it is important that the surgery team is always on board in all cases of intussusception.

References

- Cabana MD, Garcia AV. In: The 5-Minute Pediatric Consult. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2019:524-525.

- Savoie KB, Thomas F, Nouer SS, Langham MR Jr, Huang EY. Age at presentation and management of pediatric intussusception: A Pediatric Health Information System database study. Surgery. 2017;161(4):995-1003.

- Waseem M, Rosenberg HK. Intussusception. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(11):793-800.

- Edwards EA, Pigg N, Courtier J, Zapala MA, MacKenzie JD, Phelps AS. Intussusception: past, present and future. Pediatr Radiol. 2017;47(9):1101-1108.

- Marsicovetere P, Ivatury SJ, White B, Holubar SD. Intestinal Intussusception: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30(1):30-39.

- Shah SS, Zaoutis LB, Frank G, Catallozzi M, Vrecenak JD, Nance ML. In: The Philadelphia Guide: Inpatient Pediatrics. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016:539-540.

- Lin-Martore M, Kornblith AE, Kohn MA, Gottlieb M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Intussusception in Children Presenting to the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(4):1008-1016. Published 2020 Jul 2.

- Sadigh G, Zou KH, Razavi SA, Khan R, Applegate KE. Meta-analysis of Air Versus Liquid Enema for Intussusception Reduction in Children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(5):W542-W549.

- Navarro O, Daneman A. Intussusception Part 1: A review of diagnostic approaches. Pediatr Radiol (2003) 33: 79–85.

- Daneman A, Navarro O. Intussusception Part 2: An update on the evolution of management. Pediatr Radiol (2004) 34: 97–108.