Juvenile dermatomyositis is a treatable idiopathic inflammatory myopathy that causes progressive proximal muscle weakness and characteristic dermatologic phenomena. Without treatment, there is significant morbidity - and 1 in 3 patients can die.

Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is a rare cause of progressive proximal muscle weakness in the pediatric population that typically presents with symmetric muscular weakness and classic dermatologic findings. JDM must be considered early in acquired weakness in the pediatric patient, as early treatment can reverse symptoms and prevent illness progression.1 We present the case of a 6-year-old male experiencing significant weakness and hyporeflexia, who was found to have advanced JDM.

Case

A 6-year-old male presented to the pediatric emergency department with significant weakness of all extremities. He developed leg pain and weakness 6 weeks prior, which progressed to dragging his feet when walking. Three weeks after onset, while vacationing in Central America, the pain resolved. However, lower extremity weakness progressively worsened and the patient had a new onset of upper extremity weakness. He was unable to ascend stairs, sit from a supine position, elevate his arms above his head, or dress himself. At that time, he was hospitalized and presumptively treated for Guillain Barre Syndrome (GBS), initially displaying improvement following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy and physical therapy. He later developed a faint red rash on the upper half of his face, along with skin-colored papules on his elbows. Two weeks prior to the ED presentation, he began experiencing dysphagia, and a week prior, he developed abdominal pain and constipation. During symptom progression, there was no fever, weight loss, vision change, urinary change, vomiting, or diarrhea.

On arrival to the ED, he had a temperature of 36.9° Celsius, blood pressure 92/46 mm Hg, heart rate 97 bpm, respiratory rate 20/minute, and oxygen saturation 99% on room air. The examination was significant for a quietly speaking patient reclining on the gurney, with no signs of respiratory distress. The patient was profoundly weak, with head lag, strength 4/5, and hyporeflexia 1+ in all extremities. The musculoskeletal exam was negative for swelling, erythema, or tenderness. The patient was able to ambulate slowly but could not lift himself back to the gurney. There was a faintly erythematous rash around both eyes and over the malar prominences, flesh-colored papules over the elbows, and hyperpigmented papules over the dorsal metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints.

Laboratory results were significant for elevated Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) 37 mm/h (range 0–13 mm/h), creatine kinase (CK) 454 units/L (range 30–223 units/L), aspartate transaminase (AST) 111 units/L (range 13–39 units/L), aldolase 28.8 units/L (range 3.3–10.3 units/L), and Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) 934 units/L (range 140–271 units/L). Normocytic anemia was demonstrated by hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL, hematocrit 34.3%, and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 83.9 fL. Urinalysis was significant for protein 12 mg/dL (range < 12 mg/dL) and ketones (1+). White blood cells, platelets, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, C-reactive protein, and alanine transaminase (ALT) were within normal limits.

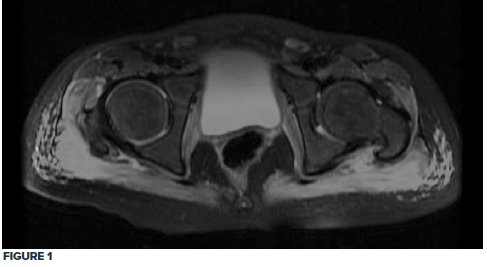

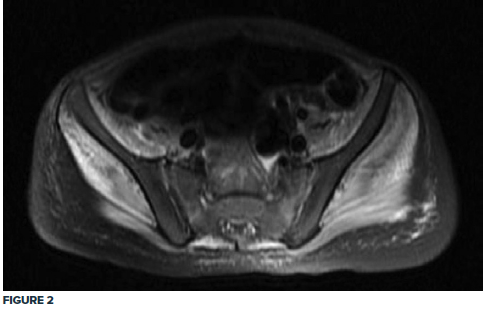

Given the clinical exam and associated elevated muscle enzymes, rheumatology consultation and pelvic MRI were completed. MRI was significant for pelvic musculature and subcutaneous tissue inflammatory changes consistent with JDM, showing a diffuse T2 hyperintense signal extending from the paraspinal muscles down to the knee extensor muscles bilaterally (Fig. 1, 2).

Treatment with a regimen of high-dose steroids, methotrexate, and physical therapy commenced, and the patient progressively improved. The patient received methylprednisolone 30 mg/kg for the first 3 days, followed by daily prednisolone 50 mg and folic acid with weekly methotrexate 12.5 mg subcutaneously.

Discussion

JDM is an autoimmune, idiopathic inflammatory myopathy that affects an estimated 3.2 children per million annually in the United States.2 It is a systemic inflammatory disease that demonstrates proximal muscle weakness and can have characteristic skin findings of heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, nailfold capillary abnormalities, and calcinosis.1,3,4 Dermatologic findings may not begin concurrently with muscular symptoms, sometimes occurring months prior to or even after weakness onset.1

Up to 80% of patients with JDM also present with signs and symptoms of systemic disease.4 These include fever, weight loss, fatigue, arthritis, interstitial lung disease, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, pain, and constipation, which can indicate ischemic complications from bowel vasculitis.1,4 Focal or generalized edema can occur, with both postulated as occurring secondary to vasculitis.5,6 While the more common periorbital and peripheral edema presentations have not been associated with a poorer prognosis, the rare generalized edema presentations are strongly associated with clinical resistance to steroids.5 Systemic capillary leak syndrome, although rare, can occur, causing hypovolemic shock, compartment syndrome, and death.7 Involvement of the cardiac system is uncommon; however, pericarditis and subclinical cardiac dysfunction have been described in some cases of JDM.1,4 Effects to the neurologic system are also uncommon in the pediatric population.4

Diagnosis is determined clinically by proximal muscle weakness, dermatologic findings, muscular enzyme elevation, and MRI evidence of inflammation of the proximal muscle groups.1,4,8 Creatine kinase levels are not typically over 1000 units/L, so other etiologies must be investigated with significant elevation, and muscle enzyme levels can also be normal in patients with JDM4. Diagnosis of JDM previously relied heavily on muscle biopsy and electromyography, though these methods are now less commonly used because of their invasive nature. The yield was also a concern with these methods, as biopsy could potentially miss areas of inflammation when muscle disease was not diffuse, and electromyography necessitated cooperation of young patients.4,8

First-line management consists of early high dose corticosteroids, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs such as methotrexate, and physical therapy.1,4,8 Without treatment, mortality can reach 30% and there is significant morbidity, whereas with prompt treatment, mortality is less than 2%.1 With early treatment, patients with JDM can make a full recovery. It is also possible to develop an intermittent relapsing or chronic pattern of symptoms, with up to 50% needing treatment for longer than 2 years.4

Conclusion

Juvenile dermatomyositis is a treatable idiopathic inflammatory myopathy that causes progressive proximal muscle weakness and characteristic dermatologic phenomena. Prognosis is significantly improved by early diagnosis and treatment, and delay can result in severe manifestations of myopathy such as global hyporeflexia, as in our patient.

Take-Home Points

- Juvenile dermatomyositis is a reversible cause of progressive proximal muscular weakness.

- Juvenile dermatomyositis does not typically affect the nervous system. However, with advanced disease, profound myopathy can result in hyporeflexia.

- Diagnosis of juvenile dermatomyositis is by clinical exam, muscular enzyme elevation, and MRI demonstrating inflammation of the proximal muscles.

- Untreated JDM can result in up to 30% mortality.

References

- Papadopoulou C, Wedderburn LR. Treatment of Juvenile Dermatomyositis: An Update. Pediatr Drugs. 2017;19(5):423-434.

- Mendez EP, Lipton R, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. US incidence of juvenile dermatomyositis, 1995-1998: results from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(3):300-305.

- Shah M, Mamyrova G, Targoff IN, et al. The clinical phenotypes of the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2013;92(1):25-41.

- Huber AM. Juvenile Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2018;65(4):739-756.

- Karabiber H, Aslan M, Alkan A, Yakinci C. A rare complication of generalized edema in juvenile dermatomyositis: a report of one case. Brain Dev. 2004;26(4):269-272.

- Shimizu M, Inoue N, Mizuta M, Sakakibara Y, Hamaguchi Y, Yachie A. Periorbital Edema as the Initial Sign of Juvenile Dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Sep 17.

- Meneghel A, Martini G, Birolo C, Tosoni A, Pettenazzo A, Zulian F. Life-threatening systemic capillary leak syndrome in juvenile dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(10):1822-1823.

- Sukumaran S, Palmer T, Vijayan V. Heliotrope Rash and Gottron Papules in a Child with Juvenile Dermatomyositis. J Pediatr. 2016;171:318.