Emergency departments across the United States have felt the effects of the growing and constantly changing list of nationwide drug shortages. These shortages have long existed on a smaller scale, but in the past 10 years the number of drug shortages has climbed to unprecedented levels. Emergency physicians now must navigate alternate drugs to replace otherwise well-established medications, adding yet another challenge to patient care in the emergency department (ED). Although federal efforts have been made to decrease drug shortages, we continue to struggle to gain access to several life-saving medications for our patients.

A Trial of the Past Decade

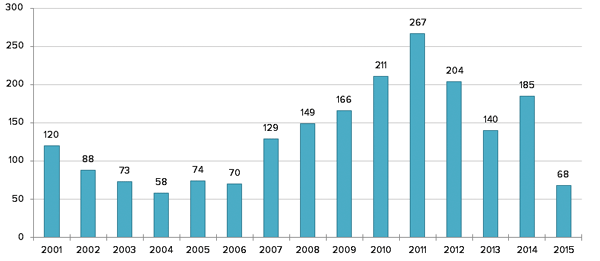

Between 2005 and 2010, the number of medications on the drug shortage list tripled (Figure 1),1,2 sparking the interest of the federal government. In 2011, President Barack Obama signed an executive order encouraging early reporting of potential disruptions to drug manufacturing and an expedited regulatory review of new drugs.3 The FDA followed by establishing the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) to identify and mitigate causes of drug shortages.4,5 FDASIA also encouraged early reporting of impending shortages by pharmaceutical companies.

The FDA estimates its efforts prevented 700+ drug shortages between 2011 and 2014.6 However, multiple new and unexpected drug shortages, including prescription drugs, continue to occur annually. Although the average number of reported new drug shortages has declined since 2011, the number of active drug shortages remains high, and many vital medications are still difficult to obtain.2 EDs are particularly hard-hit: Shortages affecting acute care medications are being seen at higher frequencies and for longer times than other drug shortages. Thus, FDASIA may be inadequate to address drug shortages impeding emergency patient care.7

Logistics

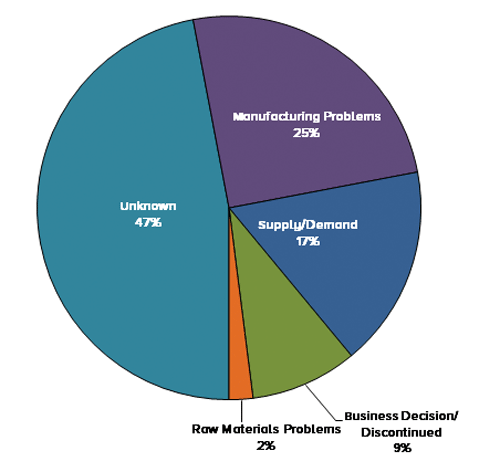

Regulatory changes in quality, evolving discrepancies between supply and demand, limited access to raw materials, and ceasing production of a medication altogether are frequently reported causes of drug shortages.8 However, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), 47% of the drug shortages in 2014 were attributed to an unknown cause as reported by manufacturers (Figure 2).9

The FDA assists in mitigating shortages by locating alternative suppliers and encouraging pharmaceutical companies to increase production of medications that are expected to experience a shortage.2 However, when a single supplier exists for a medication, any impediment to manufacturing that drug can be devastating, resulting in an unpredictable shortage with limited solutions. When this occurs, judicious use, rationing, and smaller dosages may be required until supplies can be reinstated.7,10

Drug shortages also affect the overall costs of medical care. Mismatch of supply and demand increases drug pricing (both for the drug in short supply and for the substitute medication), alternative drugs sell at different price points, and the need to acquire supplies from overseas changes packaging and shipping costs. For example, the recent shortage of normal saline production in the United States has resulted in the import of intravenous fluids from suppliers in Norway, Germany, and Spain, presumably causing prices to skyrocket.2

Disrupting Patient Care

Emergency physicians and patients expect timely, effective, and accurate treatments for acute medical conditions. Unfortunately, sterile injectable drugs germane to emergency medicine are the most frequently affected by drug shortages.7 Examples have included resuscitation drugs (etomidate, epinephrine, succinylcholine, and atropine), intravenous electrolyte solutions, and several broad-spectrum antibiotics (vancomycin, piperacillin/tazobactam, and multiple cephalosporins).7,11 In the past year, we have witnessed shortages of common medications used every day in EDs across the country: prochlorperazine, propofol, lorazepam, diltiazem, mannitol, and hypertonic saline.

Physicians, nurses, and pharmacists memorize doses of medications required to treat acute medical conditions immediately and without delay. When medications in that armamentarium are no longer available, lesser-known medications are required. Less familiarity with these substitute medications increases the risk for errors. Additionally, when the drugs previously deemed “standard of care” are no longer available, patients do not receive optimal care. So far, several deaths have been attributed to lack of necessary drugs or inferior alternatives.12 Furthermore, if drug shortages affect medications in the same class (eg, anti-epileptics or broad-spectrum antibiotics), this risk increases significantly. That being said, current evidence is largely anecdotal; further research is needed to demonstrate the actual impact drug shortages are having on patient safety in the ED.

Figure 1. New Drug Shortages by Year, January 1, 2001 to June 30, 2015

Based on information obtained from American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Drug Shortages Statistics (2015) and the University of Utah Drug Information Service.

Figure 2. Reasons for National Drug Shortages (2014)

Based on information obtained from American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Drug Shortages Statistics (2015) and from data reported by manufacturers to the University of Utah Drug Information Service.

Vital Actions

Since the spike of shortages in 2011, the government has taken steps to decrease the number of new shortages, find alternative manufacturers for short-supplied products, and give providers early warnings of potential shortages. A number of drug shortages can be expected, but shrinking the shortage list and preventing new drugs from being added to it will be vital to sustainable practice.

Providers should be aware of which drugs are on the shortage list or may experience limited availability in the near future. Formal announcements and education of ED personnel can decrease the risk of adverse events when transitioning from a commonly known drug to an alternative. For drugs used in rapid sequence intubation or cardiac arrest, post alternative medications and doses in resuscitation bays to help prevent errors. Physicians and emergency staff can advocate for their patients by becoming involved in medication management or pharmaceutical and therapeutic committees. Finally, further research on how drug shortages are affecting the ED patient population is also needed. We should feel empowered to take on the task of evaluating how the drug shortage crisis is impacting the stabilization of acute medical conditions.

Free resources are available with current information on drug shortages and FDA actions, including:

— FDA Drug Shortages Web page (fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugShortages/default.htm);

— Searchable ASHP Drug Shortages website (ashp.org/menu/DrugShortages);

— FDA's Drug Shortages mobile app, available for free on iTunes or Google Play.

Special thanks to Devon E.S. Johnson, PharmD, BCPS, Clinical Pharmacist, Emergency Medicine at Vidant Medical Center, for her assistance with this article.

References

- Chen SI, Fox ER, Hall MK, Ross JS, Krumholz HM, Venkatesh AK. National shortages of drugs used in the emergency department, 2002-2014. Poster session, ACEP15, Boston.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (2015). Drug Shortages: Current shortages. ashp.org/menu/Drugshortages/Currentshortages.

- Exec. Order No. 13588, 3 CFR. Reducing Prescription Drug Shortages. October 31, 2011.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDASIA Title VII Drug Supply Chain Provisions. fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/FDASIA/ucm365919.htm. Accessed December 8, 2015

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDASIA Title VII Overview. fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/FDASIA/ucm366058.htm. Accessed December 8, 2015.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug Shortages Infographic. fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugShortages/UCM441583.pdf.

- Mazer-Amirshahi M, Pourmand A, Singer S, Pines JM, van den Anker J. Critical drug shortages: implications for emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(6):704-11.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug Shortages. fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugShortages/default.htm.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Drug Shortages Statistics. ashp.org/DocLibrary/Policy/DrugShortages/Drug-Shortages-Statistics.pdf. Accessed December 8, 2015.

- Ventola CL. The drug shortage crisis in the United States: causes, impact, and management strategies. P T. 2011;36(11):740-57.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Drug Shortages. ashp.org/shortages. Accessed December 8, 2015.

- Fox ER, Sweet BV, Jensen V. Drug shortages: a complex health care crisis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(3):361-73.