Case

A 24-year-old male presents to the ED one night after a car accident complaining of right lower leg pain. He has no obvious deformity but has mild edema and moderate to severe tenderness closer to the ankle in the right lower extremity. He has 2+ dorsalis pedis (DP) and posterior tibial (PT) pulses and can move his toes on the right. His sensation is intact in the right foot. X-rays reveal closed, nondisplaced distal tibial and fibular fractures with minimal angulation. A posterior long leg splint is applied, and orthopedics is consulted for operative repair in the morning.

Three hours later the patient’s nurse reports that he is experiencing increased pain in his right lower leg despite a recent dose of morphine and new right foot numbness. Upon reassessment, the patient’s right toes appear paler compared to the left, although visualization is limited due to the splint. He reports paresthesias in his exposed right toes and seems to have some difficulty moving them in the splint.

What Is Compartment Syndrome?

The body is made of several compartments containing tissues that are enclosed within relatively inelastic fascial layers. Under normal conditions, the pressure within a compartment typically measures less than 10 mmHg. However, in the setting of an injury, the pressure within these compartments can increase significantly, most commonly due to bleeding and edema. As pressure rises, it can inhibit venous return from distal compartments, causing cessation of perfusion across tissue beds. This can lead to tissue ischemia and necrosis that may result in significant injury, need for massive tissue resection, permanent disability, and other long-term complications. If the pressure continues to increase, eventually the arterial flow into and distal to that compartment can be compromised, leading to more widespread ischemia and necrosis. Fractures are the most common cause of compartment syndrome, but other less commonly recognized etiologies include burns, crush injuries, electrocution, and vascular injuries.1

Signs and Symptoms of Compartment Syndrome

The classic “6 Ps” of compartment syndrome are pain, pallor, paresthesias, pulselessness, paralysis, and poikilothermia (limb that is cold to touch). These signs and symptoms very rarely occur simultaneously or are all present at once. It may be better to consider them existing along a spectrum of time and severity when evaluating for compartment syndrome. The first sign that is more specific to compartment syndrome is pain in the affected compartment with passive extension of muscles within the compartment.2 Other earlier signs of compartment syndrome include intense pain and development of a tense, “woody” extremity or compartment.

Compartment syndrome is primarily a clinical diagnosis, but the use of an intracompartmental manometer can help confirm it. This is performed by attaching a needle to a fluid-filled syringe that is then loaded into the manometer. The needle is inserted into the suspected compartment, transmitting the intracompartmental pressure to the fluid in the syringe, which the manometer measures as an approximation of the compartment’s pressure. Any compartment pressure above 30 mmHg is diagnostic of compartment syndrome. Additionally, a pressure difference of 20mmHg or less between the patient’s diastolic blood pressure and compartment pressure is also highly concerning.1

Management of Compartment Syndrome

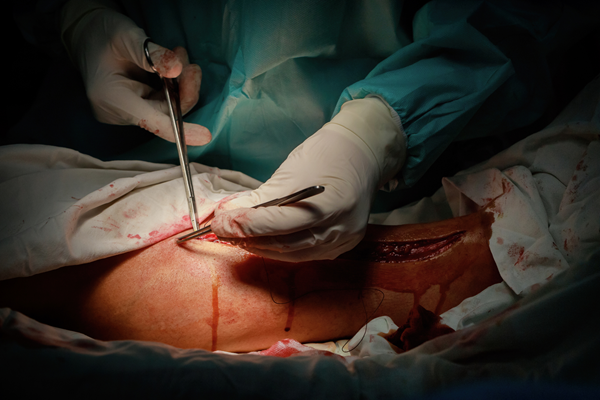

Compartment syndrome is a surgical emergency and warrants immediate surgical consultation if available. The mainstay of treatment is fasciotomy, which involves making a long incision over the affected compartment through the skin and superficial muscle. There are established anatomic locations where performing a fasciotomy offers optimal pressure relief depending on the compartment of concern.

To perform a fasciotomy, a scalpel is used to make an incision through the deep fascial plane of the affected compartment, typically in the longitudinal axis in limbs. Some compartments require fasciotomy in the transverse plane. Orthobullets has diagrams outlining the correct locations for fasciotomies for most fascial compartments.

Scenario Part 2

After discussion with orthopedics, the splint is removed. The right lower leg appears much more edematous than on initial evaluation and the entire right foot appears paler than the rest of the extremity. Additionally, the right foot feels cooler to the touch than the left, and the right DP pulse is thready. Concern for compartment syndrome prompts the use of an intracompartmental manometer. This reveals an anterior right lower leg compartment pressure of 37 mmHg, confirming the diagnosis. Orthopedics and surgery are emergently consulted. However, both services are currently occupied in the operating room and unable to assist, leading to the performance of an emergency department fasciotomy. Following induction of procedural sedation, a 25cm longitudinal incision is made on the anteromedial right lower leg extending from just above the mid-calf to 4cm proximal to the medial malleolus. Following the procedure, the right foot then shows significantly improved coloration with a strong DP pulse present.

The patient later goes to the operating room with orthopedics and surgery. His tibial and fibular fractures are repaired surgically, and he undergoes skin grafting for repair of his fasciotomy site. He suffers no permanent damage to his right foot and is eventually able to walk on his right leg.

Pearls/Pitfalls

- Recognize compartment syndrome early in the clinical course (think long bone fracture with escalating pain medication requirement)

- Remove splint/cast to perform a detailed compartment evaluation

- Suspect compartment syndrome in injuries that are not fractures

- Remember that an open fracture can also develop compartment syndrome

- Lack of a tense compartment does not exclude compartment syndrome (it can present without a palpable tense compartment externally)

- Presence of pulse in an extremity does not rule out compartment syndrome (pulselessness is a late finding)

- Continue suspecting compartment syndrome up to 48 hours after initial injury

References

- Torlincasi AM, Lopez RA, Waseem M. Acute Compartment Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Jan 16]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- OrthoInfo. Compartment Syndrome. AAOS. Aaos.org. 2022.

- Orthobullets, Leg Compartment Syndrome. Orthobullets.com, accessed 2025 Dec. 10.