An 80-year-old male with a history of aortic aneurysm presented to the emergency department for sudden worsening dyspnea. The patient was found to have an arterial saturation of 80% despite being on a non-rebreather, and rapidly escalated to needing high flow nasal cannula. Chest imaging was performed, but did not show evidence of any acute interstitial disease or evidence of a pulmonary embolism. His blood gas confirmed a low arterial oxygen saturation and the absence of any hemoglobinopathies. His physical exam revealed profound hypoxemia with a pulse oximetry of 85% despite supplemental oxygen while the patient was sitting upright. However, when the patient was supine, the saturation improved to 95%. The patient was diagnosed with platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome.

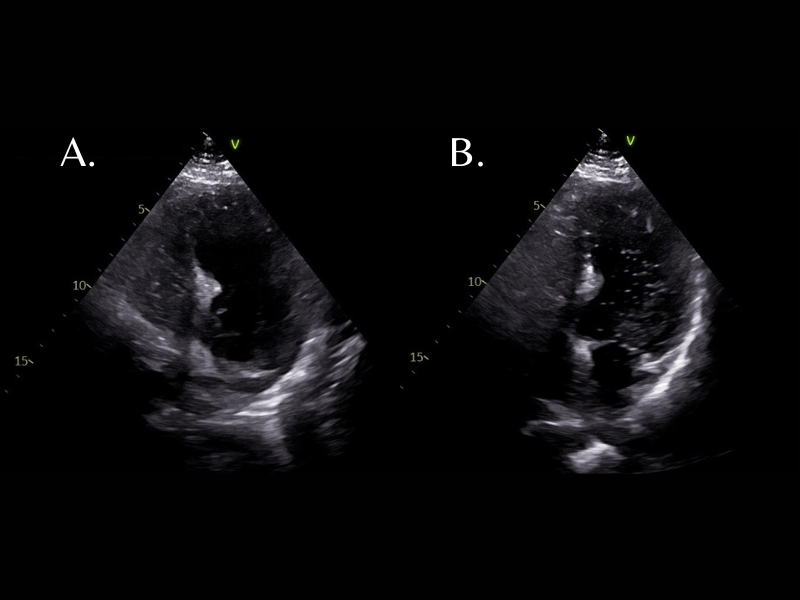

An echocardiogram with bubble study was performed, with bubbles seen in both the left and right ventricle within three cardiac cycles, suggestive of an intracardiac shunt. The patient did not have any history of liver disease or known structural heart disease. The patient underwent an intracardiac echocardiogram which confirmed the large right to left shunt via patent foramen ovale and was closed with a septal occluder. The patient’s oxygen needs resolved immediately post-procedure and he was discharged in good condition on hospital day 7.

Discussion

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome (POS) is an uncommon finding that is characterized by hypoxemia occurring when upright but improves when the patient is placed in a recumbent position. POS occurs when deoxygenated blood enters systemic circulation via intracardiac or pulmonary shunting.1 POS likely remains underdiagnosed as upright and supine vital signs are not routinely obtained.2,3 Making the diagnosis of POS in the Emergency Department leads to a narrow differential of possible underlying causes and can direct further management.

Pathophysiology

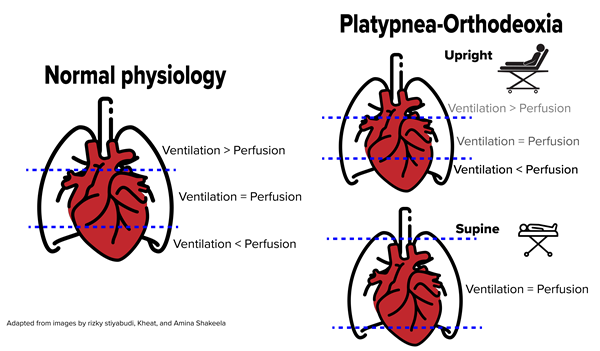

POS is characterized by deoxygenated venous blood bypassing the pulmonary capillary beds and leading to systemic hypoxemia via anatomical shunts. Positioning the patient supine creates equal blood flow through both the shunt as well as oxygenated lung, thereby equilibrating ventilation and perfusion equally across all zones of the lung.4,5

Etiologies of POS can be described as arising from either pulmonary circulation or cardiac circulation. The most common pulmonary cause is hepatopulmonary syndrome secondary to cirrhosis which can cause POS by creating pulmonary AVMs at the lung base, with shunting worsening due to the effects of gravity while upright.6 Cardiac causes of POS generally are caused by septal defects, such as patent foramen ovale (PFO), atrial septal defects, or ventricular septal defects. Cardiac septal defects generally cause left-to-right shunts and therefore do not manifest with hypoxemia initially; however, any causes of elevated right-sided pressures may cause the shunt to reverse into a right-to-left shunt, especially PFOs. More unusual causes of POS include amiodarone toxicity, restrictive pericarditis, right heart ischemia, pulmonary arterial hypertension, fat emboli syndrome, and Parkinson’s disease.

Diagnosis and Management

It is reasonable to consider POS in otherwise unexplained dyspnea and hypoxemia that is out of proportion to radiographic changes. POS can be elucidated in the physical exam at bedside by adjusting the reclining angle of the stretcher and measuring respiratory rate and oxygen saturation.2 An improvement in arterial saturation by at least 5% or PaO2 of 4 mmHg makes the diagnosis of POS.7

The initial workup of the shunt causing POS is an echocardiographic bubble study with agitated saline.7 A normal bubble study will have bubble opacification of the right ventricle but not the left ventricle. The bubble test is considered abnormal and concerning for a shunt if bubbles appear in the left ventricle within 3 cardiac cycles, whereas non-cardiac shunts are suspected if there are more than 5 cardiac cycles before bubbles appear.5 If the test is normal but suspicion remains high, there is limited evidence to suggest that an agitated D50 bubble test may be more sensitive in detecting smaller shunts, as D50 bubbles are smaller and more uniform than those of normal saline.8 However, some cases may require contrast tilt-table transesophageal echocardiography to confirm diagnosis.9

It is important to remember POS is a clinical exam finding and not a complete diagnosis. Pulmonary and cardiology consultations may be needed depending on the level of the shunt. Initial management focuses on alleviating the hypoxemia with supplemental oxygen. In pulmonary shunting such as hepatopulmonary syndrome, the care is mostly supportive. Patients with evidence of pulmonary shunting should undergo evaluation of liver disease. Cirrhosis with HPS is generally not reversible, and is considered an indication for liver transplantation evaluation. AVMs may require embolization.

In the case of intracardiac shunts, lowering right-sided cardiac pressures may reverse the direction of the shunt and thus relieve the hypoxemia. Treatments include diuretics and vasodilators. Patients with anatomical defects such as PFO are also at risk of paradoxical strokes from clots bypassing pulmonary circulation and entering arterial circulation. In severe cases of hypoxemia or if evidence of paradoxical stroke, surgical repair of any septal defects may be required.

Summary

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome is characterized by dyspnea and hypoxia that worsens when upright and improves when supine. Given the relatively narrow differential suggested by POS, the high incidence of interarterial channels including PFO, and the fairly simple bedside maneuvers to assess for POS, the emergency physician should be aware of this syndrome and its ED workup.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1: 1A Apical chamber view of the heart, showing agitated saline microbubbles in the right ventricle. 1B 3 cardiac cycles later, bubbles are seen in the left ventricle.

Figure 2: The mechanism of ventilation-perfusion mismatch during normal physiology and during POS.

Table 1: A brief list of causes of POS (not exhaustive)

|

Extra-Cardiac Causes |

Cardiac Causes |

|

Hepatopulmonary syndrome |

Patent foramen ovale |

|

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations |

Atrial septal defects |

|

Pulmonary hypertension |

Ventricular septal defects |

References

- Casanovas-Marbà N, Feijoo-Massó C, Guillamón-Torán L, Guillaumet-Gasa E, García-del Blanco B, Martínex-Rubio A. Patent foramen ovale causing severe hypoxemia due to right-to-left shunting in patients without pulmonary hypertension. Clinical suspicion clues for diagnosis and treatment. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition). 2014 Apr; 67(4):324-325.

- Porter BS, Hettleman B. Treatment of platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome in a patient with normal cardiac hemodynamics: A review of mechanisms with implications for management. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2018 Apr-Jun;14(2):141-146.

- Tighe DA, Aurigemma GP. Right-to-left shunts and saline contrast echocardiography. CHEST Journal. 2010 Aug; 138(2):246-248.

- Cheng TO. Mechanisms of platypnea-orthodeoxia: What causes water to flow uphill? Circulation. 2002 Feb 12; 105(6):e47.

- Knapper JT, Schultz J, Das G, and Sperling LS. Cardiac platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome: An often unrecognized malady. Clin Cardiol. 2014 Oct;37: 645-649.

- Cheng TO. Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome: Etiology, differential diagnosis, and management. Cathet. Cardiovasc. Intervent. 1999 May 14;47: 64-66.

- Ducey S, Cooper J. Hypovolemia resulting in platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2016 March; 50(3):482-484.

- Fuller M, Buda KG, Urbach J, Carlson MD, Herzog CA. Identification of an intracardiac shunt in a patient with recurrent cryptogenic strokes: Are dextrose solutions more sensitive? CASE (Phila). 2021 Jan 7;5(2):123-125.

- Khauli S, Chauhan S, Mahmoud N. Platypnea. [Updated 2024 Jan 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.