Abstract

We present a rare case of spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) in a previously healthy 26-year-old male with no traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Suspected contributing triggers include a recent inflammatory response following flu-like symptoms—possibly related to a viral illness such as COVID-19—and engagement in high-intensity, weight-bearing physical activity. Although the precise etiology remains unclear, this case underscores the need for heightened clinical awareness of SCAD in younger populations and highlights the importance of addressing the significant psychological burden associated with this diagnosis.¹

Introduction

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is an uncommon but increasingly recognized cause of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), particularly in younger and otherwise healthy individuals.1 The etiology of SCAD is multifactorial, encompassing hormonal, genetic, vascular, emotional, and physical stressors.1,2 While most cases occur in middle-aged women, SCAD can affect men and younger individuals.1,2 This report details a rare presentation of SCAD in a 26-year-old male and explores potential physiological and psychosocial contributors. The case also highlights the need for comprehensive support systems tailored to young SCAD survivors.1

Case Report

A 26-year-old previously healthy male presented to urgent care with complaints of “lung irritation” exacerbated by deep breathing and bilateral elbow discomfort. He reported a history of chest discomfort three weeks earlier associated with flu-like symptoms—cough, congestion, and myalgias—self-managed with Tylenol, Motrin, and activity modification. Although symptoms initially resolved, they recurred and prompted medical evaluation. He denied fever, headache, cough, chest pain or pressure, abdominal pain, or bowel/bladder changes at presentation.

Medical and Social History

The patient had no significant past medical history or family history of cardiac disease. Social history was notable for regular heavy weightlifting, vaping tobacco, occasional alcohol use, and use of pre- and post-workout supplements (specifically C4 products).

Initial Evaluation

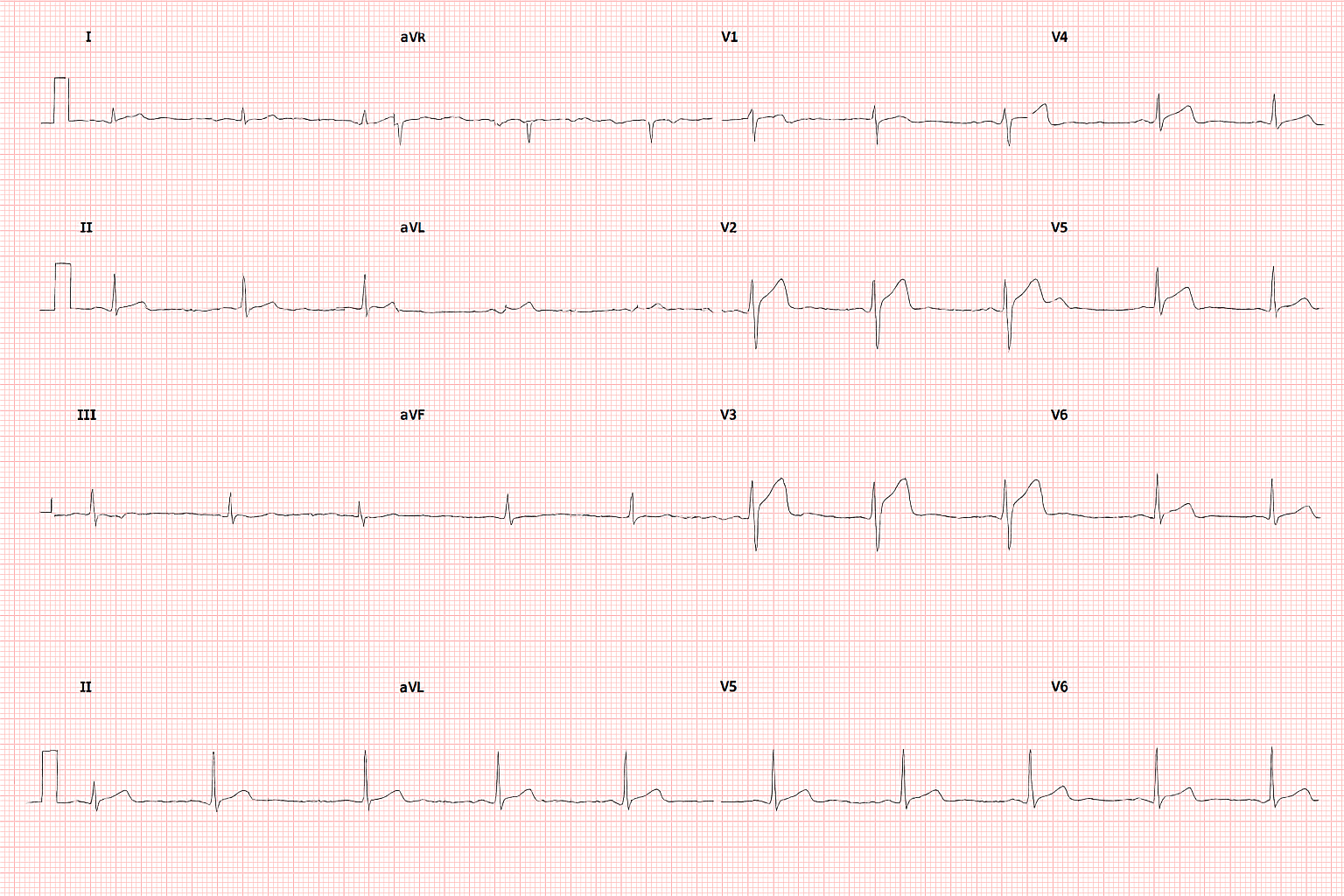

An ECG performed at urgent care raised concern for an anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), prompting transfer to the emergency department.

- Vital Signs: Heart rate: 105 bpm; Blood pressure: 160/83 mmHg

- Repeat ECG: Persistent ST-segment elevations in anterior leads

- Bedside Echocardiogram: Left ventricular apical hypokinesis with preserved ejection fraction (60–65%) and borderline concentric LV hypertrophy; no valvular abnormalities or pericardial effusion

- Laboratory Findings: Elevated troponin level (5.43 ng/mL)

Given the concerning clinical picture, the patient was taken emergently for coronary angiography.

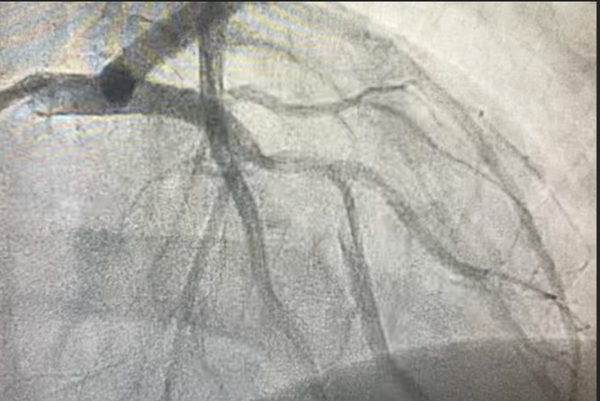

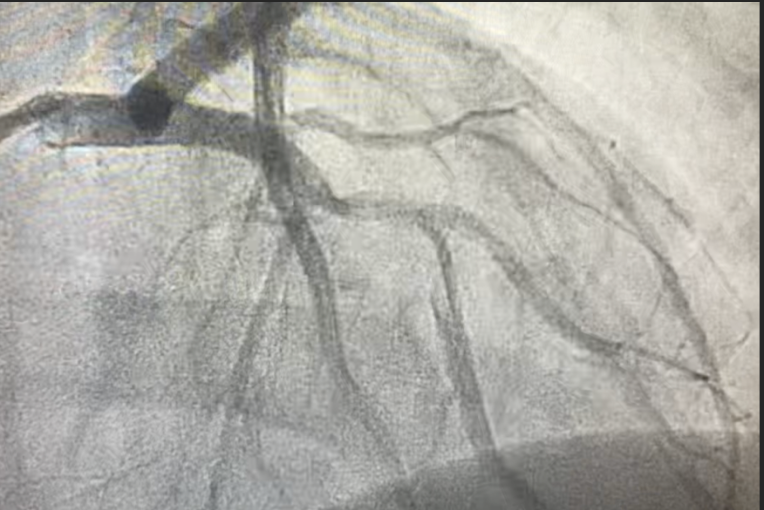

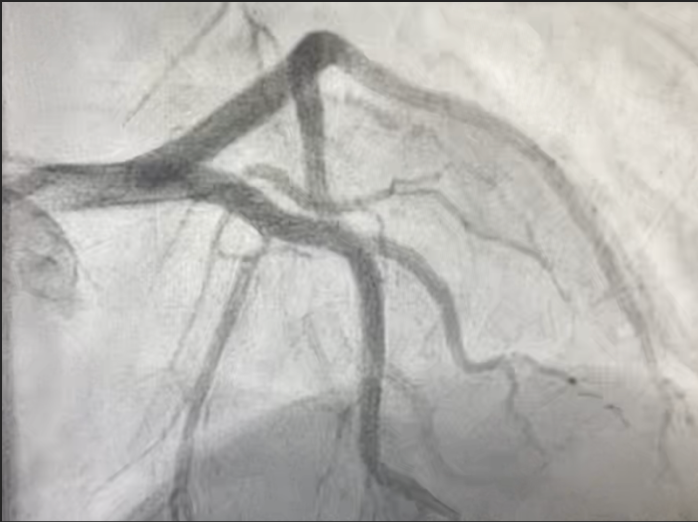

Cardiac Catheterization Findings

- Dissection of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery extending beyond the takeoff of the principal diagonal branch;

- Total occlusion of the apical LAD, likely due to distal embolization;

- Two drug-eluting stents were successfully deployed to restore flow.

Post-Procedure Course

The patient tolerated the procedure well. A repeat echocardiogram the following day revealed a left ventricular apical thrombus. He was initiated on triple antithrombotic therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and apixaban. His hospital course was uncomplicated. He remained hemodynamically stable with no recurrence of symptoms and was discharged on hospital day 4.

At a 5-week follow-up, the patient reported no recurrence of symptoms and had successfully initiated a structured cardiac rehabilitation program.

Discussion

Although SCAD is typically associated with middle-aged women, this case highlights its occurrence in young men without conventional risk factors.1,2,3 Over 90% of SCAD cases occur in women, and affected patients typically have fewer traditional cardiovascular risk factors but higher rates of systemic arteriopathies, such as fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD).3,4 This underscores the importance of vascular screening in all SCAD cases, including in men.

Established and suspected risk factors for SCAD include:

- Female sex and hormonal changes

- Underlying arteriopathies (e.g., fibromuscular dysplasia)

- Genetic predispositions

- Intense physical or emotional stressors1,2

In this case, a recent systemic inflammatory response, possibly triggered by a viral infection, combined with high-intensity resistance training may have contributed to vascular vulnerability and dissection.1,2,4

A proposed "two-hit" model of SCAD development, especially relevant in the COVID-19 era, posits that vascular injury may result from an interaction between a predisposed vasculature (e.g., post-viral inflammation or stress cardiomyopathy) and a second inciting factor like sympathetic activation or physical stress.5 Although our patient had no confirmed COVID-19, his recent illness may have contributed to such a mechanism.

SCAD angiographically presents with hallmark features including intramural hematoma, with or without an intimal tear, and typically involves the LAD artery.1,3 In our case, the LAD dissection was confirmed and treated with PCI. While conservative management is generally favored due to the high spontaneous healing rates, PCI is indicated in high-risk cases with ongoing ischemia or hemodynamic instability, as in our patient.1,2,3

Intravascular imaging with IVUS or OCT can support diagnosis when angiography is equivocal and assist with interventional planning.2 Though not performed in this case, its consideration is warranted in unclear or recurrent cases.

Psychological Impact

The psychological toll of SCAD can be profound, particularly among young patients. Higher rates of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress have been documented in SCAD survivors, particularly in women and peripartum patients.1 Contributing factors include:

- Diagnostic uncertainty and fear of recurrence

- Lack of clear, evidence-based secondary prevention guidelines

- Disruption of lifestyle and perceived health autonomy

- Inconsistent or inadequate support systems1

Although online communities offer some level of peer support, many lack medical oversight and may inadvertently perpetuate fear or misinformation. This case underscores the need for structured, medically guided psychosocial support systems tailored to the unique needs of young SCAD patients.1,2,4

Conclusion

This case illustrates an atypical presentation of SCAD in a young, previously healthy male and reinforces the importance of broadening diagnostic considerations beyond traditional demographics.1,2,3,4 It also demonstrates the utility of invasive evaluation and intervention in unstable presentations. Furthermore, the case highlights the significance of post-event care, including mental health support, patient education, and screening for underlying arteriopathies. Finally, growing recognition of COVID-19–related inflammatory and sympathetic triggers calls for increased vigilance in evaluating young patients with recent viral illness and atypical cardiac symptoms.5

References

- Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(8):961-984.

- Offen S, Yang C, Saw J. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD): a contemporary review. Clin Cardiol. 2024;47(6):e24236.

- Lewey J, El Hajj SC, Hayes SN. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: new insights into this not-so-rare condition. Annu Rev Med. 2022;73:339-354.

- Saw J, Humphries K, Aymong E, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: clinical outcomes and risk of recurrence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(9):1148-1158.

- Shojaei F, Habibi Z, Goudarzi S, et al. COVID-19: A double threat to takotsubo cardiomyopathy and spontaneous coronary artery dissection? Med Hypotheses. 2021;146:110410.