Nasal septal abscesses are an uncommon diagnosis in emergency medicine, with limited analysis and discussion in the otolaryngology literature.

Case

A 31-year-old otherwise healthy male patient presented to the ED for 9 days of nasal pain. The pain was described as being localized to his left nare with associated feelings of nasal obstruction and complaints of difficulty breathing through his nose. He reported Afrin use – 2 sprays once daily for 2 days – without symptomatic relief. He had never had this pain previously. He denied nasal substance ingestion, nasal trauma, previous nasal surgery, and recent dental surgery. Additionally, he denied recent illness to include fever/chills, eye drainage, eye swelling, rhinorrhea, sinus pain, and cough. He did report using clippers to trim his nose hair.

On arrival to the ED, the patient's vital signs were stable and he was afebrile satting at 99% on room air. On physical exam, there was no appreciable swelling or tenderness to palpation of the dorsum and lateral margin of the external nose. On further inspection of the nasal cavity, the patient's septum on the left side (involving the inferior nasal turbinate and nasal vestibule) demonstrated significant mucosal swelling and mild purulent drainage with scant blood. Despite the absence of similar swelling on the right side of the septum, the patient did have tenderness to palpation of the septum bilaterally. Labs and imaging were deferred given the clinical stability of the patient.

Attempts at expressing purulence from his septum were performed at bedside with some success, but complete drainage was largely limited by the patient's pain. Given the limitations of successful drainage and duration of symptoms, otolaryngology on call was paged for further evaluation and management.

Discussion

Nasal septal abscesses are an uncommon diagnosis in emergency medicine with limited analysis and discussion in the otolaryngology literature. Traditionally, nasal septal abscesses are the result of traumatic facial injuries with 75% occurring as a direct complication of nasal trauma.1 Nearby extension of a dental or sinonasal infection is the second most common cause.2 While a handful of cases of spontaneous nasal septal abscesses are reported in patients with chronic asymptomatic HIV and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, incidence in immunocompetent adults is exceedingly rare. Only three published case reports are found in the PubMed database in the past 35 years.

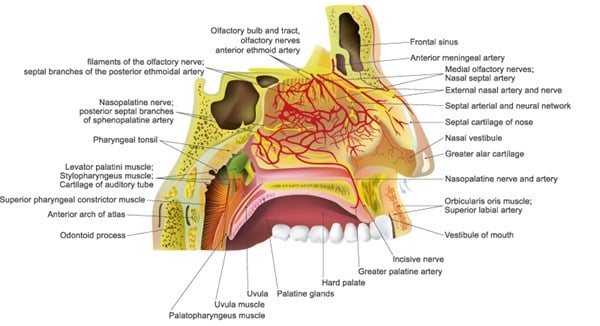

The nose is a mixed bony and cartilaginous structure with a midline septum dividing the nasal cavity into right and left sides. The septum's lack of direct vascularity highlights the physiologic importance of the vascular rich mucoperichondrium that lines the septal cartilage. The sphenopalatine artery, the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries, the superior labial artery, and the greater palatine artery travel through this mucoperichondrium providing the cartilaginous septum its blood supply via diffusion.3,4 When the interface between the septal cartilage and its source of blood supply is interrupted, septal ischemia ensues leading to tissue necrosis and possible infection.1 Pressure from a small traumatic hematoma or a small abscess can in this way impair blood flow and enable large abscess formation.

The urgency of this diagnosis is supported by the following complications. As tissue necrosis results – secondary to ischemia either from a traumatic hematoma or abscess – the pressure it generates can lead to septal perforation and subsequent saddle nose deformity – a structural problem.4 It is the destruction of this cartilage that permits a unilateral nasal septal abscess to become bilateral while promoting the expansion of infection to surrounding areas – a functional concern. Orbital cellulitis, impaired development of the nose and maxilla in children, cavernous sinus thrombosis, subarachnoid empyema, intracranial abscess, and bacteremia leading to sepsis have all been documented complications given the anatomical proximity of the septum to these areas.5,6 The potential for these complications to become life-threatening reinforce the importance of prompt recognition and intervention.

The most common presentation of a nasal septal abscess is nasal obstruction and pain with associated swelling and erythema of the dorsum of the nose and nasal septum.6,7 If not properly or thoroughly examined, this diagnosis could be mistaken as nasal septal deviation or inferior nasal turbinate hypertrophy.6 A CT scan is the imaging modality of choice for differentiating nasal septal abscess from superficial cellulitis. The decision to include a CT brain with contrast and/or CT soft tissue head and neck with the CT scan of the maxillofacial region depends on the clinical presentation and associated symptoms of the patient's complaint.

When a patient presents to the ED with an exam concerning for nasal septal abscess, incision and drainage for culture and gram stain and parenteral antibiotics should be initiated without delay. If having difficulty with bedside drainage or there appears to be obliteration of the septum, call otolaryngology on call for operative drainage and reconstruction with initiation of antibiotics in the interim. While staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen to cause nasal septal abscesses, determining your patient's risk factors for methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is imperative if severe complications from bacterial dissemination are to be avoided.8

Case Conclusion

Our patient was taken directly to the operating room by the otolaryngology resident for incision and drainage and discharged home with Augmentin for 10 days, Bactroban twice daily to the left nare, and saline spray 3-4 times daily. He was evaluated in their clinic 2 days following drainage, at which point his packing and doyle splint were removed from the left nare. There was no active purulent drainage after the incision site was explored and his pain was noted to be improving. The patient's culture resulted as a pan-susceptible staphylococcus aureus, so his antibiotic regimen was continued. Additionally, the patient was counseled on the possibility of underlying immunodeficiency and future structural complications from his treated abscess. The patient had a negative HIV blood test in 2013. The patient was evaluated one additional time by the subspecialist and released from their care after an uneventful recovery.

Take-Home Points

- Nasal septal abscesses are a potentially life-threatening diagnosis that can be mistaken for nasal turbinate swelling or septal deviation highlighting the importance of a thorough physical exam.

- While common symptoms include nasal pain and nasal obstruction, ask patient’s about systemic signs of infection.

- Statistically, non-traumatic nasal septal abscesses occur in immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals making it important to ask patients about family history and sexual history.

- The treatment of nasal septal abscesses includes incision and drainage, parenteral antibiotics, and pain control.

- It is important to counsel patients on the structural complications and cosmetic defects that can result from nasal septal abscesses.

References

- Ambrus PS, Eavey RD, Baker AS, Wilson WR, Kelly JH. Management of nasal septal abscess. The Laryngoscope. 1981;91:575-582.

- Beck, AL. Abscess of the nasal septum complication acute ethmoiditis. JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery. 1945;42(4):275-279. doi:10.1001/archotol.1945.00680040359006

- Quong, WL, Arneja, JS. Nasal septal hematoma. In Operative Techniques in Pediatric Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2020:Chapter 45.

- Huang, YC, Hung PL, Lin HC. Nasal septal abscess in an immunocompetent child. Pediatrics and Neonatology. 2012;53(3):213-215. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2012.04.011.

- Cain, J, Roy S. Nasal septal abscess. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal. 2011;90(4):144,147.

- Adnane, C, Adouly, T, Taali, L, Belfaquir, L, Rouadi, S, Abada R, Roubal, M, Mahtar, M. Unusual spontaneous nasal septal abscess. Journal of Case Reports and Studies. 2014;3(3):1-3. http://www.annexpublishers.com/articles/JCRS/3302-Unusual-Spontaneous-Nasal-Septal-Abscess.pdf.

- Debnam, JM, Gillenwater, AM, Ginsberg LE. Nasal septal abscess in patients with immunosuppression. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2007;28(10):1878-1879. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0708.

- Cheng, LH, Wu, PC, Shih, CP, Wang, HW, Chen, HC, Lin, YY, Chu, YH, Lee, JC. Nasal septal abscess: a 10-year retrospective study. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2019;276(2):417-420. doi: 10.1007/s00405-018-5212-0.