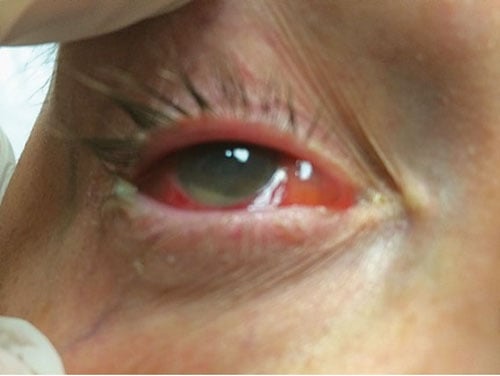

A 58-year-old female presents to the ED with a chief complaint of right eye pain. She underwent cataract surgery 2 days prior and has experienced worsening pain and redness for the past 24 hours. On exam, she has mild swelling of the right upper eyelid, diffuse conjunctival injection, and an obvious hypopyon (Figure 1). Her pupils are equal and reactive, and her extraocular muscles are intact with no worsening pain with movement. Fundoscopic exam reveals moderate haziness of the right cornea. You are drawing a blank on a differential, and your attending suggests endophthalmitis.

Background

Emergency physicians are faced with the task of identifying life-, limb-, and eyesight-threatening diseases on a daily basis. Some of these conditions are more common and obvious than others. Endophthalmitis, although rare, is a vision-threatening disease that cannot be missed. It is an inflammatory condition involving the intraocular cavities of the eye (ie, the aqueous and/or vitreous humors) and is usually caused by infection.

Endophthalmitis is classified as exogenous or endogenous.

Endogenous endophthalmitis, which is less common (occurring in 2-15% of all cases), is caused by blood-borne pathogens that permeate the blood-ocular barrier. It is typically seen in patients who are immunocompromised (such as in patients with diabetes, AIDS, chronic renal failure, leukemia, or lupus), and in patients who are bacteremic.1

Exogenous endophthalmitis, on the other hand, is most commonly caused by trauma, contiguous spread from an infected corneal ulcer, or any surgical procedure that disrupts the globe (eg, cataract removal, glaucoma bleb filtering surgery, secondary lens implantation, vitrectomy, corneal transplantation, intravitreal injections).2 The incidence of exogenous endophthalmitis in patients following cataract surgery or intravitreal injections is approximately 0.03%, or 3 in 10,000 post-operative patients.3 In patients with open globe ruptures, the incidence has been reported to be as high as 30% depending on the nature of the injury and the hospital setting.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Most patients with post-operative endophthalmitis will present within the first few days to weeks after surgery. One large study found that the most common presenting symptoms included blurry vision (94%), eye redness (82%), pain (74%), and eyelid edema (34.5%).4,5 The most common physical features included the presence of hypopyon (85%), hazy media (79%), and vision loss (26%). From an emergency medicine standpoint, the diagnosis of both endogenous and exogenous endophthalmitis should be made clinically. An ophthalmologist will then be able to confirm the diagnosis by obtaining a vitreous sample that can be sent for gram stain and culture.6,7

In patients with postoperative acute exogenous endophthalmitis, gram-positive organisms account for almost 90% of cases. While S epidermidis (belonging to the group of coagulase-negative staphylococci) is the single most common cause, S aureus and streptococcal species have also been isolated. On the other hand, while nearly any organism can cause endogenous endophthalmitis, fungal infections are an important consideration because they can occur in up to 50% of patients. Candida albicans is by far the most frequent cause of fungal cases, occurring 75-80% of the time.4 The classic fundoscopic finding in these patients is coalesced cotton-ball opacities in the vitreous, known as the “string of pearls” sign.8

Emergency Department Management

Endophthalmitis is an ophthalmological emergency and treatment is best left in the hands of an ophthalmologist. The mainstay of treatment for all types of endophthalmitis is intravitreal antibiotics +/- vitrectomy.9 For traumatic endophthalmitis, there is some evidence that systemic antibiotics are also indicated.10 For endogenous endophthalmitis, systemic antibiotic treatment is certainly indicated and should be targeted at treating the underlying source of the bacteremia. Fluconazole must be added if there is suspicion for candidal endophthalmitis. Regardless, the best and most efficient action in treating these patients is to involve ophthalmology early on in their care.

Conclusion

Delayed diagnosis of endophthalmitis can be catastrophic, and emergency medicine providers must have a low threshold for consulting ophthalmology as soon as the diagnosis is considered. While the excitement of “eye pain” may pale in comparison to the hustle and bustle that surrounds myocardial infarctions, gunshot wounds, and strokes, the consequences of missing this disease can be just as grave, and the diagnosis just as rewarding.

References

- Romero CF, Rai MK, Lowder CY, Adal KA. Endogenous enophthalmitis: case report and brief review. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(20):510-514.

- Pathengay A, Khera M, Das T, Sharma S, Miller D, Flynn HW Jr. Acute Postoperative Endophthalmitis FollowingCataract Surgery: A Review. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2012;1(1):35-42.

- Taban M, Behrens A, Newcomb RL, et al. Acute endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(5):613-620.

- Brod RD, Flynn HW Jr. Endophthalmitis: current approaches to diagnosis and therapy. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1993;6:628–637.

- Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study, A Randomized Trial of Immediate Vitrectomy and of Intravenous Antibiotics for the Treatment of Postoperative Bacterial Endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113(12):1479-1496.

- Vaziri K, Schwartz S, Kishor K, Flynn H. Endophthalmitis: state of the art. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2015;9:95-108.

- Brod RD, Flynn HW Jr, Kaplan LG. Endophthalmitis. In: Schlossberg D, ed. Clinical Infectious Disease. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:109-116.

- Sadiq M, Hassan M, Agarwal A, et al. Endogenous Endophthalmitis: diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2015;5(1):32.

- Durand ML. Endophthalmitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:227-234.

- Andreoli C, Andreoli M, Kloek C, et al. Low Rate of Endophthalmitis in a Large Series of Open Globe Injuries. Am J of Ophthal. 2009;147(4):601-8.