Emergency department (ED) physicians are trained and expected to think on our feet, to make the best of unusual circumstances and to provide the best care for patients no matter the obstacles. This training was tested to the limit in October when Hurricane Matthew stormed up the East Coast and came barreling inland.

Within 48 hours, the small, stalwart city of Lumberton, North Carolina, was underwater, and lives were changed forever. Nobody had seen the environmental disaster looming.

Background

Lumberton, located just off the Atlantic coast, is a quaint city fringed by the lush banks of the Lumber River. Nobody expected the river, which is usually a beautiful and calming element, to so forcefully exacerbate the effects of Hurricane Matthew.

A week prior to the hurricane, several unyielding thunderstorms drenched the area. When the storm was its strongest on Saturday, Oct. 8, 2016, the already saturated soil gave way to uprooted trees and toppled power lines. But, it was the record-high water levels from the Lumber and other rivers, along with subsequent flooding, that caused so much devastation. The storm took the lives of 28 people and displaced several thousand residents throughout the state.

While members of the Southeastern Health EM team ended up at different locations — Jenna Santiago-Wickey, DO, at a shelter and Elizabeth Gignac, DO, at the hospital with Krelin Naidu, DO, Gregory Capece, DO, and many other emergency medicine residents — they remained united in their efforts to support one another while caring for a community in crisis.

Saturday, Oct. 8

Disaster Medicine at the Hospital

Dr. Gignac: Friday was the calm before the storm. But, as the rain picked up in the evening and into Saturday, dumping 9 inches within 24 hours, I realized the storm was more catastrophic than anticipated. Suddenly, water levels began to rise, making more roads impassable and knocking the power out at the hospital — fortunately, the generators kicked in and restored our power.

Dr. Naidu and Dr. Capece: As we walked into work on Saturday we realized the hospital was running on the backup generator, one of two we had. People began swarming the emergency department waiting room — some for refuge, others for serious medical aid. This quickly became an all-hands-on-deck operation. Initially, certain lights and electronics were disabled in favor of essential services. However, our progressive power predicament required the air conditioning be turned off as well. Despite the dimly lit ominous heat wave that surrounded us in the department, we dug deeper into our roles to provide the best care possible to our much-in-need patients.

The post-shift evening raised the difficult question of whether to brave increasingly flooded roads to go home, or to be safe and practical within the confines of the hospital. Many residents of the emergency medicine, family medicine, and internal medicine programs decided to band together and spend the night in the hospital. Our program director, Dr. Elizabeth Gignac, was there at our side. The hospital graciously provided rooms and cots. We were truly “residents” of Southeastern Health.

Disaster Medicine at the Shelter

Dr. Santiago-Wickey: I was scheduled to ride with EMS the week of the hurricane. As the storm hit, callously washing away our plans, we all scrambled to help however we could. I made my way to St. Pauls High School, which was serving as a shelter when blocked roads made it impossible for me to reach the base. The first day was frustratingly chaotic. We had limited supplies — only stethoscopes and glucometers — and a small inventory of medication. Pushing through the disorder, we hurriedly implemented a system and began assessing and caring for patients.

Sunday, Oct. 9 – Monday, Oct. 10

At the Hospital

Dr. Gignac: Sunday was eerily quiet and peaceful with sunny, cloudless skies. The water levels receded a little and the roads even opened up enough for some of us to return home. Just when we thought we had reached the end of our rather brief ordeal, Monday came, swelling water levels to record highs and vigorously wiping more defenseless residents out of their homes.

Dr. Naidu and Dr. Capece: Monday presented us with a new challenge: no more running water. The rumor was the levees had broken and some of the city water pipes had burst. Our EMS Dispatch was handling more than 200 calls at any given time; one by one, survivors started to arrive. Many of these individuals were rescued from their homes and were very ill. Some had run out of essential medications, including basic oxygen. Others had oxygen supplies, but no power to run their machines. We modified our fast track area as a temporary oxygen bar for patients struggling to breathe.

Meanwhile, in the emergency department, the temperature continued to rise. Certain blood chemistries were unable to be run because we lacked necessary water for the equipment. We were unable to get the most basic labs on the sickest of our patients. Our attendings urged us to provide the best care possible through thorough histories and physical exams, which utilized our most fundamental skills learned in medical school.

At the Shelter

Dr. Santiago-Wickey: We saw a variety of needs that included panic attacks, diabetes management, and dialysis treatment. One patient was overdue for a catheter change, and when we finally received a new one for him on the third day, we ended up using the locker room as a procedure room.

The fear, lack of information, and general distress contributed to a lot of frustration among hurricane victims and, in turn, made the atmosphere extremely tense. Some evacuees criticized our zero-tolerance policy for narcotics. Meanwhile, others saw our presence as an opportunity to have an exam, requesting to have their blood pressure and heart rate checked.

Some of our most pressing concerns centered around so many people living in such close quarters, the lack of hygiene, the risk of contamination, and the potential for a flu outbreak. Nearly 400 people stayed in the school that first week, filling the gymnasium with row upon row of cots.

Tuesday, Oct. 11 – Thursday, Oct. 13

At the Hospital

Dr. Gignac: Tuesday was one of the most challenging days. We did not have any water, which made it impossible to flush toilets and cook as well as perform dialysis and other procedures and tests. Additionally, the lack of air conditioning sent inside temperatures to a sweltering 90 degrees.

Dr. Naidu and Dr. Capece: We were tired. Many residents, nurses, and even attendings had to spend multiple nights away from the comfort of their homes and families. We had no access to showers and limited use of the restrooms. We were still running on limited power and we were told the water pipes were still attempting to be fixed.

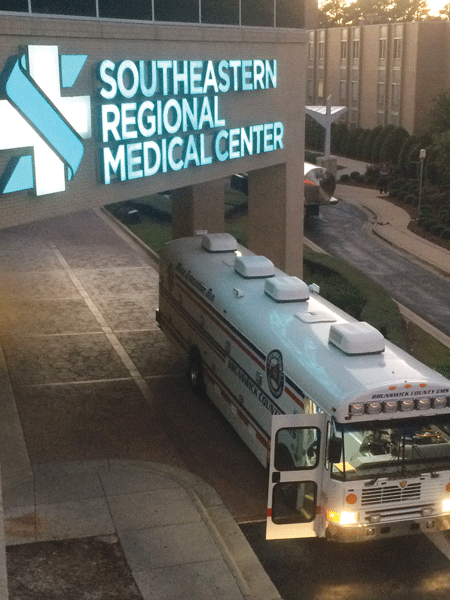

We looked out the window and saw numerous tractor trailers pulling into the parking lot. Two trailers with generators and another team of vehicles, Carolinas MED-1 Mobile Hospital Unit, had arrived with much-needed aid. This mobile hospital and command center offered coordination and relief in our resource-depleted crisis.

Dr. Gignac: The self-sustaining mobile hospital with 14 beds and a two-room suite for the ICU parked outside the ED and took some of our low acuity patients. Then, on Wednesday, as if working conditions weren't difficult enough, we occasionally experienced complete blackouts. The generators sent black smoke into the air, foreshadowing their total failure.

Dr. Naidu and Dr. Capece: Code Black - our generators had failed. Our greatest concern was the ICU. These patients were the sickest in the hospital, many of whom required mechanical ventilation, now not an option. Ambu-Bags were attached to all endotracheal tubes, and hand ventilation was required to keep many of our patients alive. The staff all took turns ensuring every individual received the appropriate care with the limited resources available.

Dr. Gignac: That short time during the blackout on Wednesday felt like an eternity. We all felt a little helpless, when we only had 1 headlamp that a colleague used to check on patients. It was at that point that leadership strongly considered closing the hospital. Then, as if on cue, the emergency generators kicked in, enabling us to remain functioning.

Dr. Naidu and Dr. Capece: Our objective at this point was to transfer all critically ill patients, especially those requiring ventilator support to our neighboring hospitals. In the dark, we were communicating with medical intensive care units and emergency departments at UNC, Duke, and Cape Fear Valley. Although the situation seemed like it was out of control, as emergency residents and attendings, we felt comfortable enough to handle the stress. We were in our element.

Over the next few hours we cleared the ICU as helicopters and ambulances safely transferred patients. It was amazing to see so many diverse staff members from every department coming together in a cohesive force to do what was right for each and every patient.

Dr. Gignac: We evacuated the 8 patients from the ICU; however, more people who were oxygen-dependent, chronically ill, and debilitated started trickling into the ED. We were all a little perplexed because, while we saw people coming in, our patient count remained below the daily average of 180. On Thursday, we also gained some much-needed access to pressurized water via several tanker trunks that connected to the hospital's plumbing. Soon, the blackouts ceased and conditions at the hospital began to stabilize.

Still, some roads remained closed, and it was heartbreaking to see so many hurricane victims, often in disbelief and without anywhere to go, seek shelter at the hospital. As hard as it was to turn them away, we had to be very selective and only admit those who met strict criteria. Managing our resources and our patients' expectations as well as sending victims to safe, alternative locations, turned out to be one of our most difficult challenges.

At the Shelter

Dr. Santiago-Wickey: Fortunately, I was able to return home every day to the warm embrace of my husband. But, when the night fell quiet, I could not help but think about those who were not as lucky, particularly the children. Volunteers entertained the kids at the shelter with music and games, yet the kids had no idea this was not just a temporary distraction, but their indefinite new normal.

Being from Long Island, I was accustomed to dealing with hurricanes, but I never imagined one would make it so far inland and cause so much damage.

The Aftermath

Dr. Santiago-Wickey: While riding with EMS the second week I was exposed to even more of the storm's devastating consequences. We saw people still living in their shattered homes with trees collapsed on top of them. We were also on-scene when firefighters extricated a body from a car that had been submerged in 10-15 feet of water. While they suited up in jumpers, many of us rubbed Vicks VapoRub under our noses in an attempt to mitigate the smell of the decomposing body. It was by far the worst event I had ever experienced. Nevertheless, it taught me not to take anything for granted.

Dr. Gignac: As time passed, people began returning home to face the daunting cleanup process. During this phase, we saw more incidents of carbon monoxide poisoning, gastrointestinal issues and skin infections from exposure to toxic substances. Water levels remained high for about a week, and crime incidents increased. Now, months have passed, and the community is still adjusting.

Lessons Learned

Dr. Gignac and Dr. Santiago-Wickey: Before the hurricane, we had disaster response and relief plans in place. Moreover, as emergency clinicians, we are always mentally prepared for the unknown. However, we learned that while you can prepare to a certain extent, nobody is truly capable of predicting or being fully prepared for what may happen during a storm. You just have to keep a clear mind, communicate effectively, and find solutions – no matter how challenging the circumstances.

Our colleagues handled the situation with incredible professionalism and resolve. Hurricane Matthew taught us just how extraordinary and brave our team is and how proud we are to be a part of such a strong community.

Dr. Naidu and Dr. Capece: As emergency medicine residents, this experience was truly humbling. Many people lost everything — cars, homes, and more. No one would have expected Hurricane Matthew to have had this profound effect on Lumberton. It is simply amazing the support that came from the local community, the state, and even the federal government to help us through this tragic period. The spirit of our town was struck hard, but Lumberton and its people will endure.