We report the case of an 18-year-old male with a history of chronic cannabis use who presented to the emergency department with acute onset shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, and facial swelling. He endorsed persistent vomiting over the preceding week and described temporary symptom relief of his nausea with hot showers. On presentation, he was tachycardic, hypertensive, and tachypneic, with palpable crepitus extending from the neck to the clavicles. Chest imaging revealed spontaneous pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema without evidence of pneumothorax or esophageal perforation. He was managed conservatively with high-flow oxygen, IV fluids, and antiemetics, including haloperidol and capsaicin cream, resulting in clinical improvement. This case illustrates the rare but important association between cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) and spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM), underscoring the importance of recognizing CHS and its complications in adolescents with chronic cannabis use.

|

|

||

|

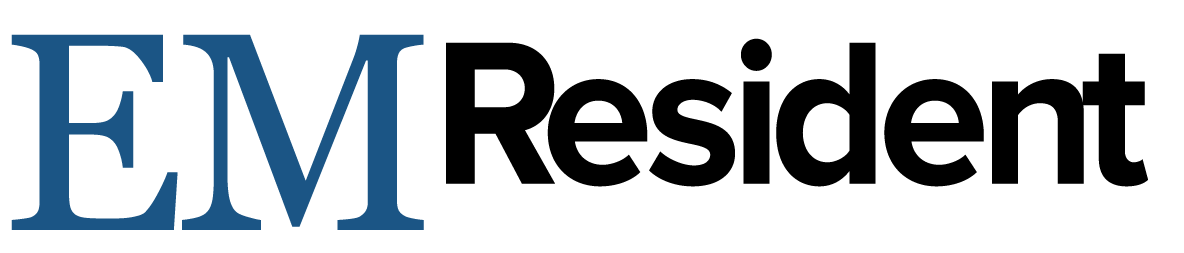

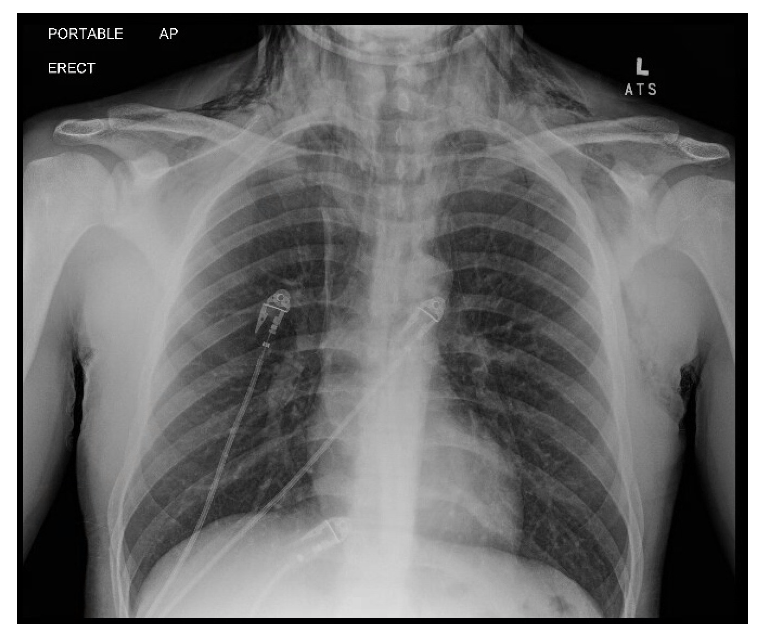

Figure 1: Chest X-Ray: Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in the supraclavicular region in the base of the neck and left hemithorax |

Introduction

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is a condition characterized by cyclic episodes of severe nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain in individuals with chronic cannabis use. Despite its increasing recognition, CHS remains underdiagnosed, particularly in adolescents, and can be associated with a range of complications, some of which are potentially life-threatening. One such complication is spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM), a rare but serious condition where air accumulates in the mediastinum without any clear traumatic cause. Although SPM is typically benign, it can present with significant respiratory distress and requires prompt identification and management. This case highlights the uncommon but critical association between CHS and SPM, emphasizing the importance of considering CHS in young patients with chronic cannabis use and understanding the potential for serious complications in these cases.

|

|

||

|

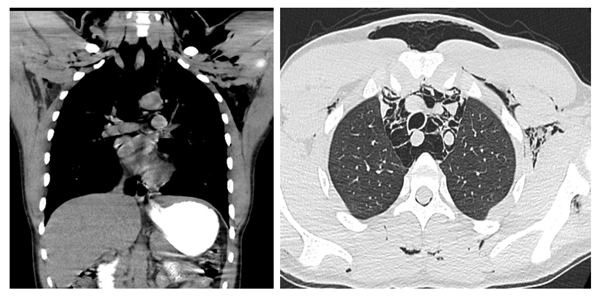

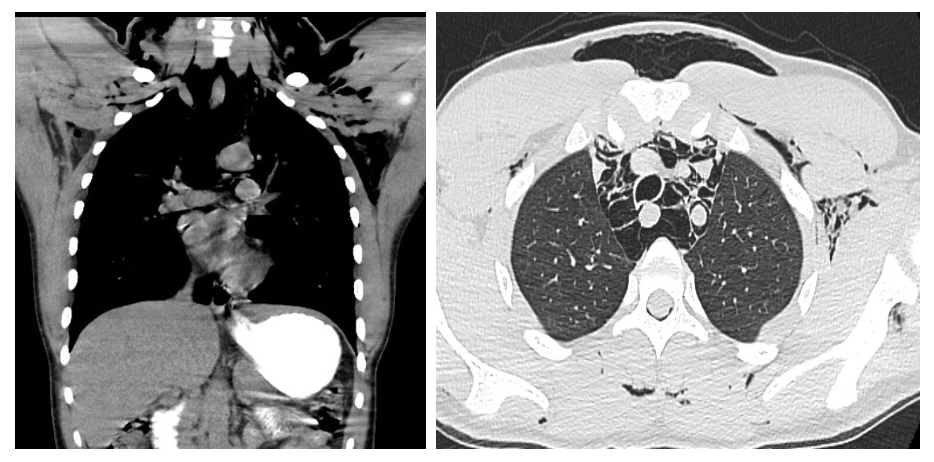

Figure 2,3: CT chest with oral contrast: Extensive pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema, without evidence of esophageal perforation |

Case Report

An 18-year-old male with no significant past medical history other than chronic daily cannabis use presented to the emergency department via EMS with complaints of progressive shortness of breath, persistent nausea and vomiting, and new-onset facial swelling. He reported a one-week history of worsening nausea and emesis, with facial swelling developing over the preceding two days. Notably, he described temporary relief of nausea with hot showers, a behavior commonly associated with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS).

The patient denied chest pain, trauma, asthma, allergies, recent travel, or a personal/family history of thromboembolic disease or coagulopathy. Upon arrival, he appeared visibly anxious and uncomfortable, actively vomiting. He was afebrile, but tachycardic (HR 130s), hypertensive (BP 160/92 mmHg), and tachypneic, with an oxygen saturation of 99% on 2L via nasal cannula placed by EMS.

Physical examination revealed notable facial swelling and extensive subcutaneous crepitus over the bilateral neck and supraclavicular areas. He was able to speak in full sentences without evidence of trismus, drooling, stridor, or oropharyngeal swelling. Pulmonary auscultation revealed clear bilateral breath sounds, with no audible Hamman’s sign. Cardiac and abdominal examinations were unremarkable.

Initial chest radiograph demonstrated pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and upper thorax. A CT chest with oral contrast was obtained to evaluate for esophageal perforation, given the presence of pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in the setting of repeated emesis. Imaging confirmed extensive pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema, but no contrast extravasation, no pneumothorax, and no radiologic evidence of esophageal rupture were identified. These findings effectively ruled out esophageal perforation, supporting a diagnosis of spontaneous pneumomediastinum secondary to barotrauma from forceful vomiting. Laboratory evaluation was notable for leukocytosis (WBC 16.2 × 10⁹/L), acute kidney injury (creatinine 2.31 mg/dL, which improved with IV fluid resuscitation), and a positive urine drug screen for THC. Arterial blood gas (ABG) revealed a mixed alkalosis: primary respiratory alkalosis with secondary metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.62, pCO₂ 27 mmHg, HCO₃⁻ 28 mmol/L).

The patient was managed with high-flow oxygen, intravenous fluids (2L Lactated Ringer’s), and antiemetic therapy, including haloperidol (5 mg IV), lorazepam (2 mg IV), and topical capsaicin 0.025% cream applied to the abdomen. He was admitted to the medical service for continued supportive care and symptomatic management. Consultations with pulmonology and gastroenterology were obtained; no procedural intervention was required.

Over the course of hospitalization, the patient’s symptoms improved significantly. Repeat chest imaging showed resolution of subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum. He was discharged after a 2-day admission with strict instructions to abstain from cannabis use and to follow up for repeat imaging in 3–6 weeks.

|

|

||

|

Figure 4: Bilateral buccal edema |

Discussion

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) is an uncommon condition, particularly in adolescents. It typically results from alveolar rupture due to elevated intrathoracic pressure, allowing air to dissect along vascular sheaths into the mediastinum—a process known as the Macklin effect. Common triggers include forceful vomiting, coughing, Valsalva maneuvers, asthma exacerbations, and inhalational drug use, such as cannabis. Most cases are benign and managed conservatively with supportive care.1

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is a paradoxical reaction seen in chronic cannabis users, characterized by cyclic nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Though cannabis has antiemetic properties, prolonged use can desensitize or downregulate cannabinoid (CB1) and TRPV1 receptors, leading to worsening gastrointestinal symptoms. The relief often reported with hot showers or topical capsaicin is thought to result from TRPV1 receptor stimulation, which may alter visceral sensation and redistribute splanchnic blood flow. Additional contributing factors include frequent high-dose use, accumulation of THC in fatty tissues, and possible genetic susceptibility. Symptoms typically improve only after cessation of cannabis use.2

In this case, the patient’s combination of facial swelling, vomiting, and subcutaneous emphysema prompted concern for esophageal perforation (Boerhaave syndrome)—a life-threatening emergency. However, contrast-enhanced CT imaging effectively ruled out perforation. The patient's arterial blood gas revealed a mixed alkalosis, consistent with vomiting and hyperventilation. This case highlights the importance of considering CHS in young patients with chronic cannabis use and the need for thorough evaluation to distinguish benign SPM from more serious conditions requiring surgical intervention.

Management

Uncomplicated SPM is treated conservatively with high-flow oxygen, analgesia, antiemetics, and rest. This patient was treated with IV fluids, haloperidol, lorazepam, and topical capsaicin, consistent with CHS protocols. High-flow oxygen enhances nitrogen washout and promotes absorption of free air. Abstinence from cannabis is the cornerstone of CHS management and recurrence prevention.2 The patient improved with conservative care, and imaging showed regression of mediastinal air. He was discharged with outpatient follow-up and advised on cannabis cessation. Recurrence of both CHS and SPM is rare with sustained abstinence.

Conclusion

This case highlights the diagnostic complexity and clinical significance of spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) in the setting of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS), particularly among adolescents with chronic cannabis use. Although initially concerning for esophageal rupture—a life-threatening condition—this patient’s presentation was ultimately attributed to forceful emesis and barotrauma in the context of CHS. The case reinforces the importance of maintaining a broad differential when evaluating young patients with vomiting, facial swelling, and subcutaneous emphysema. Prompt imaging and exclusion of surgical emergencies are critical to guide appropriate, conservative management. As cannabis use continues to rise, emergency clinicians must be vigilant in recognizing CHS and its potential complications. Patient education regarding cannabis cessation is essential to prevent recurrence and minimize future risk.

Conflict of Interest: There was no funding related to this case report. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- D’Arcy M, McMahon L. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management. Uptodate.com, 2023.

- Duggan K, Gohil R. Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum: Causes, Diagnosis, and Management. Uptodate.com, 2023.

- Allen J, Poage M, Young B. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome in Chronic Cannabis Users: A Clinical Review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(7):583-587.

- Lee N, Soria M, Park J, et al. Pneumomediastinum: A Review of Spontaneous Cases and Management Strategies. Thorac Surg Clin. 2019;29(2):149-157.