The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

CDR Koch, LT Shulby, and LT Tovar are employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties.

Acute aortic dissection (AAD) is the most common — and most catastrophic — manifestation of acute aortic syndromes, characterized by a tear in the aortic intima that allows blood to enter the media, creating a false lumen and separating the intimal and medial layers. Acute aortic dissection is a true medical emergency with a high mortality rate that increases 1-2% per hour after symptom onset, if left untreated.1-2 The dissection flap may propagate antegrade or retrograde, leading to a spectrum of life-threatening complications including aortic rupture, cardiac tamponade, acute aortic regurgitation, myocardial ischemia, stroke, and malperfusion syndromes.3

The incidence of aortic dissection is estimated at 5–30 cases per million people per year, with a predilection for men and peak incidence between 50 and 70 years of age. Hypertension is the most prevalent comorbidity, present in up to 100% of cases, and connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome are important risk factors for early-onset disease.2-3

Case Presentation

An 87-year-old male with a past medical history notable for abdominal aortic aneurysm, atrial fibrillation managed with a Watchman device, and hypertension presented to the emergency department via EMS for sharp, throbbing right hip pain along with right lower extremity (RLE) weakness and atypical sensations of “warmth” in the extremity that began after working in his yard, approximately 1 hour prior to arrival. He also experienced a brief episode of substernal chest pain at symptom onset, which had completely resolved by the time of presentation.

The patient presented with hemodynamically appropriate vital signs. Physical exam demonstrated a RLE that was cool to touch compared to the left with nonpalpable and non-dopplerable pulses. The patient demonstrated 0/5 strength with right hip flexion, 3/5 with right knee flexion and 0/5 with extension. The patient was unable to dorsi- or plantarflex on the right. He additionally endorsed diminished sensation of the RLE compared to the left. Shortly after initial examination, the patient promptly developed sudden hypotension with a recorded manual blood pressure of 70/30 in the right upper extremity. Mental status, however, was largely unchanged. A manual left upper extremity blood pressure was measured at 128/80.

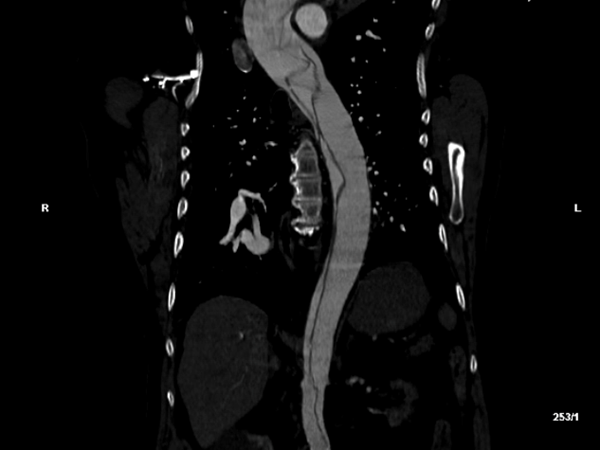

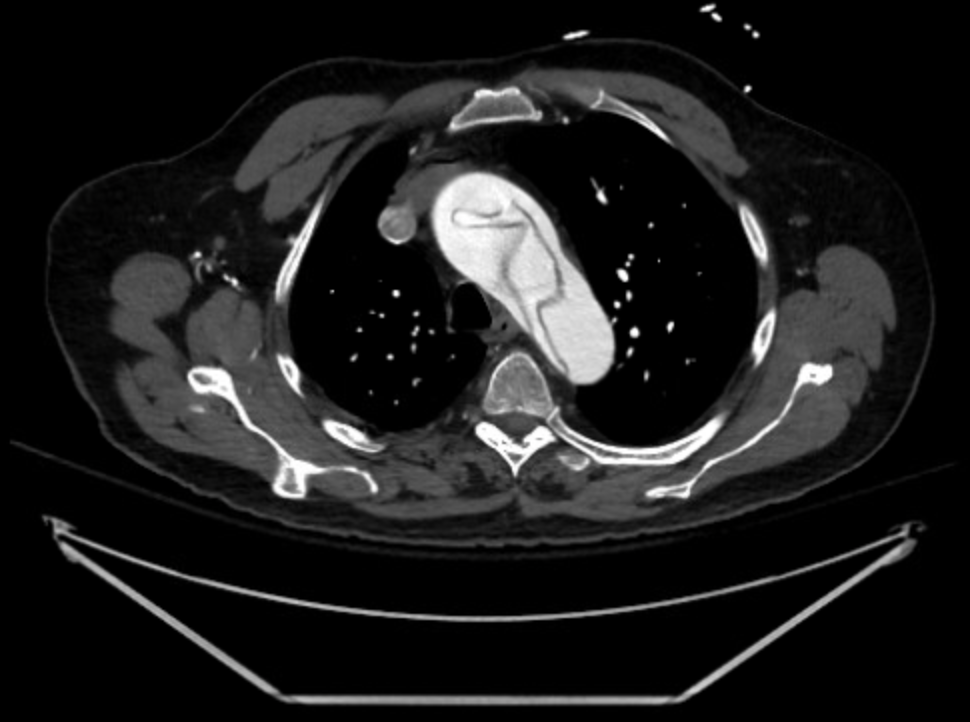

Based on these exam findings, an emergent CTA of the aorta was obtained, and demonstrated an extensive type A dissection involving the aortic valves, all 3 arch vessels, the right coronary artery, and the right common iliac artery with loss of signal at the right external and femoral arteries. The celiac, inferior mesenteric, and left renal arteries were all supplied by false lumens.

Clinical Examination Findings

Acute aortic dissection (AAD) most commonly affects males aged 60 to 70 years old with a history of hypertension. AAD classically presents as an abrupt onset of chest, back, or abdominal pain, most often described as sharp, stabbing, or tearing in nature. Clinical presentation, however, may vary based on location of the dissection with type A dissections most commonly presenting with chest pain or aortic regurgitation, while type B dissections are more commonly associated with back or abdominal pain and limb ischemia. It is important to recognize that patients may present without pain, especially older adults and women, which may delay recognition of acute aortic pathology.2

Potential physical exam findings include pulse deficits, asymmetric blood pressures between limbs (>20 mmHg difference), new diastolic murmur consistent with aortic regurgitation,3 signs of end-organ malperfusion (e.g. stroke symptoms, myocardial ischemia, paraplegia, oliguria, bowel ischemia), or evidence of shock or cardiac tamponade. CT angiography of the aorta is the gold standard for the diagnosis of AAD, with sensitivities upwards of 100%.2

Discussion and Management

This patient’s presentation was extremely unusual compared to the classic symptomatology of AAD. While the majority of patients with AAD present with chest pain, back pain, or both, a number of aortic dissections are missed in the emergency department due to atypical clinical presentations.4 It is estimated that 6% of AAD cases are considered painless dissections, which are more associated with neurologic deficits or altered levels of consciousness, such as syncopal events. These atypical presentations are associated with higher morbidity than the classic symptoms.5-6 In the present case, the patient’s isolated right hip pain reflected acute limb ischemia likely secondary to dissection-related obstruction of the iliofemoral vasculature.

Early diagnosis and management are essential in reducing mortality.1-2 In addition to immediately consulting cardiothoracic surgery, management for AAD include heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) control, along with liberal analgesia.4 Attention should first be turned to reducing shear forces against the dissected aortic wall via lowering the heart rate to less than 60 beats per minute. As many of these patients present with hypertension, blood pressure should also be reduced to a goal systolic of ≤ 120 and diastolic of ≤ 80, while ensuring adequate end-organ perfusion.3 Short-acting IV beta blockers such as esmolol are first-line agents, and if unsuccessful in controlling HR and BP, nicardipine can be used.3-4 Ultimately, immediate surgical intervention is the definitive treatment for type A AAD.2

Case Resolution

Following diagnosis, the patient was immediately started on an esmolol bolus and infusion. He was additionally placed on supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula due to hypoxia. The patient was transferred by helicopter to the nearest tertiary aortic center where he underwent aortic root replacement and ascending and total trunk replacement while on cardiac bypass. His operative course was complicated by a blowout of the right coronary button, necessitating placement back on bypass for re-anastamosis. Postoperatively, he developed RLE compartment syndrome requiring a 4-compartment fasciotomy and cardiogenic shock that required vasopressor and inotropic support. He also required continuous renal replacement therapy that was subsequently transitioned to intermittent hemodialysis, however he has since fully recovered renal function. The patient was discharged neurologically intact to an inpatient rehabilitation after a 22-day hospital course, and ultimately returned home, regaining functional independence.

Take-Home Points

- Acute aortic dissection may present atypically, often without the classic "tearing" chest or back pain. Instead, patients may present with syncope, neurologic deficits, pulse deficits, or even painless dissection.

- Pain location and associated symptoms can vary based on the dissection's extent and may mimic other conditions, necessitating a high index of suspicion, especially in patients with risk factors or unexplained hypotension, syncope, or neurologic findings.2-3

- Initial management of acute aortic dissection focuses on aggressive heart rate and blood pressure control (target systolic BP <120 mm Hg and HR <60 bpm) using intravenous beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and pain management with opioids.

- Rapid imaging — preferably CT angiography in stable patients — is essential for diagnosis. Early multidisciplinary involvement is critical, as mortality increases by 1–2% per hour if untreated.

Figure 1: Transverse (left) and sagittal (right) sections of the patient’s initial computed tomography radiographic study, demonstrating a complex aortic dissection flap extending from the aortic valve through the iliac bifurcation.

References

- Gouveia e Melo R, Mourão M, Caldeira D, Alves M, Lopes A, Duarte A, Fernandes e Fernandes R, Mendes Pedro R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the incidence of acute aortic dissections in population-based studies, J Vasc Surg. 2022 Feb; 75(2)709-720, ISSN 0741-5214.

- Mussa FF, Horton JD, Moridzadeh R, Nicholson J, Trimarchi S, Eagle KA. Acute aortic dissection and intramural hematoma: A systematic review. JAMA. 2016 Aug 16;316(7):754–763.

- Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black III J, Augoustides JG, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: A report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

- Levy D, Sharma S, Grigorova Y, et al. Aortic dissection. [Updated 2024 Oct 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- Smedberg C, Hultgren R, Olsson C, Steuer J. Incidence, presentation and outcome of acute aortic dissection: results from a population-based study. Open Heart. 2024 Mar 13;11(1):e002595.

- Imamura H, Sekiguchi Y, Iwashita T, Dohgomori H, Mochizuki K, Aizawa K, Aso S, Kamiyoshi Y, Ikeda U, Amano J, Okamoto K. Painless acute aortic dissection. - Diagnostic, prognostic and clinical implications. Circ J. 2011;75(1):59-66.