The health care delivery system is a complex industry in which physicians simultaneously act as clinicians, participants, and managers.1 As such, it is becoming increasingly critical that physicians understand basic business principles to successfully advocate for patients and create impactful changes in health systems.

Highlighting the importance of business education during physicians' training, many of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies for resident physicians involve management and health systems knowledge.2 However, a recent national needs assessment of residents demonstrated that many training programs provide minimal education in these competencies.3 Consequently, trainees report having weak exposure to critical topics like negotiations and billing, and attending physicians corroborate a lack of training in critical business principles throughout all stages of their careers.4

CRITICAL LEARNING GAP

To help address this critical learning gap that increasingly affects physicians’ abilities to advocate for patients and create impactful change, our team used Kern’s six-step approach to curriculum development to build a pilot business curriculum for resident physicians.5 Our goals in this process were to:

- Educate learners in basic business principles as they relate to the practice of medicine;

- Assess learning through a series of surveys and interviews;

- Develop a sustainable curriculum model that can be adopted across organizations.

Given the increasing importance and overall lack of current avenues for education in critical business principles of medicine, we are sharing our business curriculum development process to help others adapt similar programs. Here, we describe the creation, implementation, and assessment of this pilot business curriculum at a 4-year Emergency Medicine (EM) training program in the United States, while highlighting its potential for broad applicability across organizations and specialties.

CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT & DESIGN

To construct the foundation of the curriculum, our team first conducted an extensive literature review of existing business curriculum proposals in medicine.6-17 Next, our team of business-trained physicians worked closely with education experts at our institution to combine the topics and lessons from this literature review with data from a 2019 national needs assessment of business training in EM.18 Through a consensus-driven process, we honed in on eight business topic areas that are critical for modern physicians: personal finance, models of practice, negotiations, billing and coding, emotional intelligence (EQ), operations, malpractice, and change leadership.

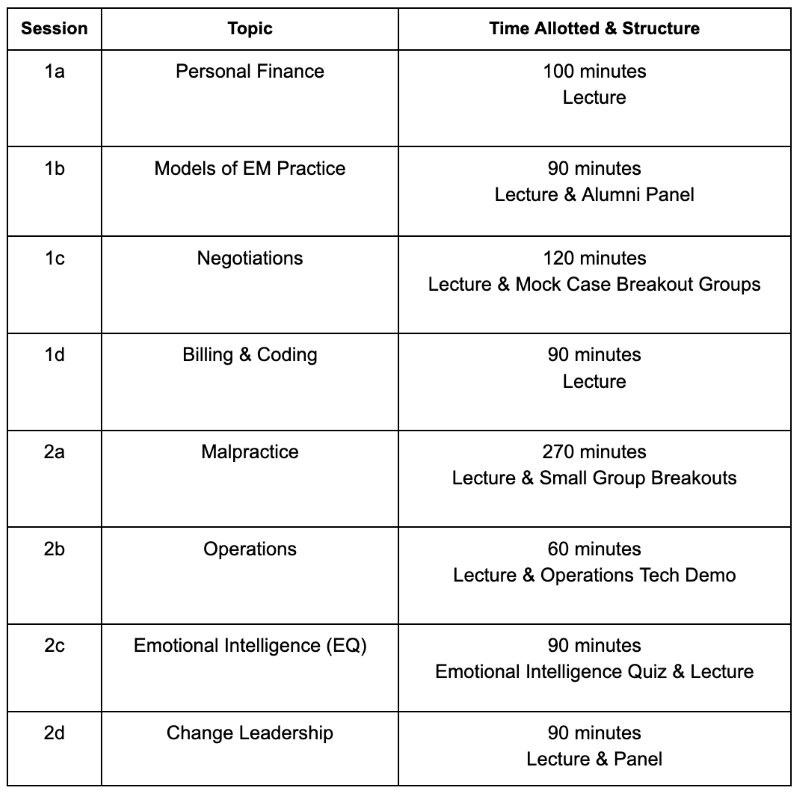

Ultimately, we developed these topic areas into an eight-session curriculum that we implemented over 18 months (August 2020–February 2022) at a 4-year EM training program in the United States. The sessions were included as part of the residency's weekly didactics and varied in length from 60-90 minutes for lectures or panel-based discussions to 240 minutes for an immersive malpractice experience (Figure 1).

Fig.1. Eight-session business curriculum topics and time dedicated

Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, all the sessions were held virtually. We utilized our institution’s network of faculty and alumni, as well as national experts, to serve as presenters for each session. We provided each speaker with objectives—developed through iterative discussions by our team in conjunction with education expert consultation and focused on the upper tiers of Bloom’s taxonomy—to ensure all critical aspects of each topic were covered.19 Prior to each session, one of our team members met with the speaker(s) to review content and ensure alignment with the objectives. We recorded most of the sessions to enable asynchronous review, in addition to developing an open-access reference document with high-yield notes from each session.

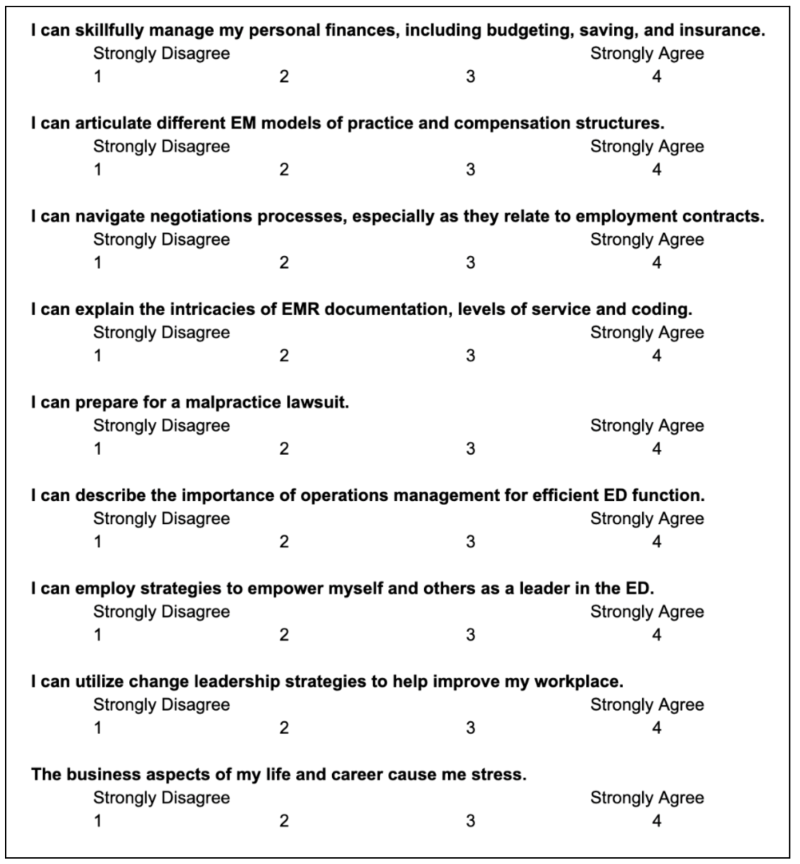

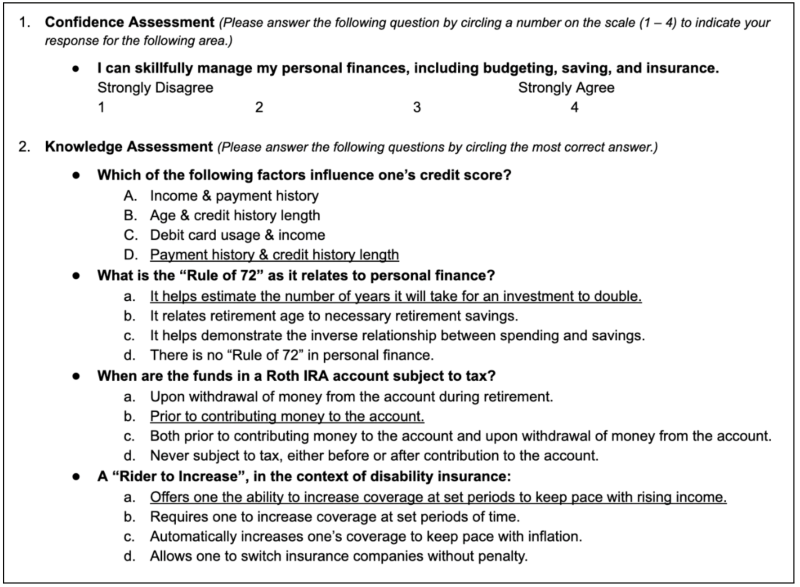

To assess impact and further refine the curriculum, we conducted a series of IRB-approved surveys and interviews with learners. All survey and interview content was developed through iterative discussions among our team in conjunction with institutional education experts. Surveys were administered electronically via Qualtrics; they were made available by email link and a QR code during individual education sessions. The curriculum was bookended with identical pre-intervention and post-intervention surveys to assess learners’ comfort levels with each of the curriculum topics via a 4-point Likert scale. We also conducted pre- and post-session surveys for each of the eight sessions; these surveys combined 4-point Likert-based comfort level questions with several multiple-choice knowledge assessment questions that were developed based on session objectives with education expert review. Respondents who completed both the pre- and post-session surveys for at least 1 session were matched and paired, and those responses were then used for significance testing; non-paired responses were excluded. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank was used to compare pre- and post-session Likert comfort level questions, and McNemar's test was used to evaluate the non-parametric pre- and post-session binary knowledge assessment variables.

In addition to surveys, we also conducted focused interviews to gain deeper insight into the curriculum's impact on learners. One of the authors interviewed 5 trainees, selected via convenience sampling among session attendees, over a 2-month period following a semi-structured protocol. Interview questions were created through iterative discussions among the team and examined participants' prior experiences before exploring how the curriculum impacted them, including which sessions were particularly helpful and less impactful, and why. Themes and direct quotations were recorded in real time. Through iterative rounds of discussions, our team derived themes categorizing learners' experiences with the curriculum. Exemplar surveys and the interview guide are available in Figures S1-3 in the supplement.

Fig. S1-S3. Exemplar surveys and interview guide assessing business curriculum

PILOT CURRICULUM IMPACT

The pilot curriculum was offered to 58 EM residents, and nearly every resident participated in some portion of the curriculum over its 18-month implementation; an average of 35 learners were present at each individual session. Twenty-seven learners completed the pre-curriculum survey (response rate=46.7%), and 14 completed the post-curriculum survey (response rate=24.1%). 12.5% of learners reported some level of prior business training, such as a master’s degree. In the pre-curriculum survey, 26% agreed or strongly agreed that they felt comfortable with the curriculum topics; this rose to an average of 73% in the post-curriculum survey.

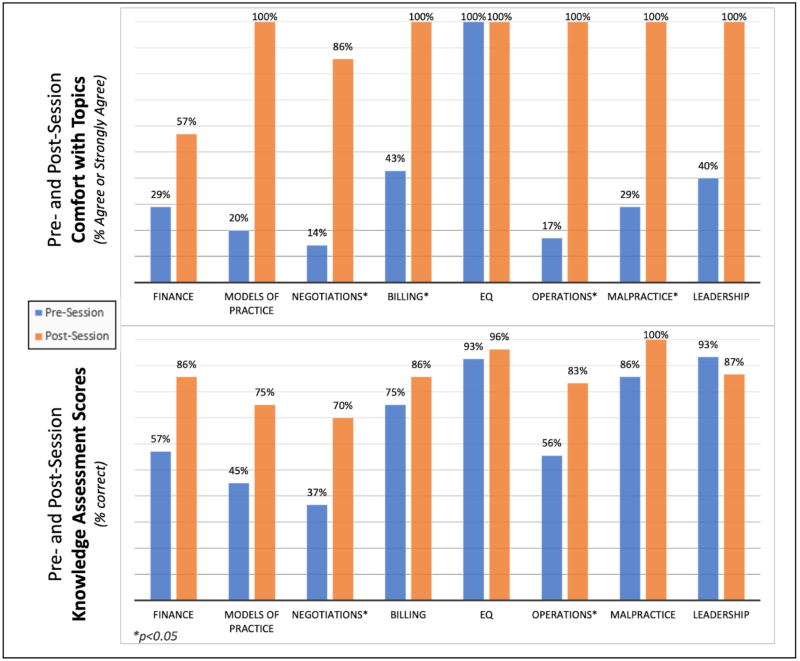

Across the 8 sessions, 10-24 learners completed the pre-session survey, and 6-19 learners completed the post-session surveys. An average of 7 learners per session submitted both the pre- and post-session surveys. Seven of the eight sessions demonstrated an increase in comfort levels and knowledge scores (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Resident confidence in business acumen, pre- and post-curriculum

On average, 37% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that they were comfortable with topic areas before each session; this increased to an average of 93% after the sessions.

Knowledge scores rose from an average of 68% correct pre-session to an average of 85% correct post-session.

Four sessions showed statistically significant rises in comfort levels:

- Negotiations;

- Billing and Coding;

- Operations;

- Malpractice (p<0.05).

Half of the sessions demonstrated rises in knowledge scores by over 25%, and the Negotiations and Operations sessions showed statistically significant increases in knowledge scores (p<0.05).

Interviews revealed that, in addition to presenting foundational concepts, the curriculum created tangible impacts on learners' lives, with participants commenting that they "have started setting aside an emergency savings fund and saving more for retirement" and "feel more comfortable having a framework for how to think about potential job options in the future."

Ultimately, our team successfully created both a process and a pilot program for resident physicians that fills a critical education gap. By combining existing proposals in the literature with needs assessment data to identify critical topic areas, followed by developing session objectives, content, and assessments in collaboration with business and education experts, we developed a curriculum that increased learners' comfort with and knowledge of most session topics while receiving overwhelmingly positive reviews in interviews.

As part of a continuous improvement process, our team is incorporating survey results with feedback from interviews to improve future iterations of the course. Planned improvements include additional focus on specific takeaways and direct applications to life in medicine and beyond for each session.

LIMITATIONS

Although our pilot curriculum has broad potential applicability across institutions and specialties, both our curriculum and this project have limitations. First, the curriculum was implemented at a single EM residency training program, with a relatively small number of participants and variable response rates to individual surveys. Second, the surveys included in the study relied heavily on self-assessment of comfort, when physicians have a documented limited ability to self-assess.20 Finally, this work does not explore potential long-term applications of the demonstrated knowledge gains.

CONCLUSION

Basic business knowledge is a critical skill for every physician working in today's complex health system environment, and our pilot curriculum suggests that this knowledge can be achieved in part through a longitudinal business curriculum during residency training. The curriculum we developed is effective at increasing resident physicians' comfort with and knowledge of critical business aspects related to the practice of medicine. Notably, since the original development of this pilot curriculum in 2020, several authors have introduced targeted business education as well; the recent emergence of numerous educational programs in this realm reaffirms the importance of this topic.12-15

Building on our process, other organizations may be able to implement or enhance similarly impactful educational programs. Future work is needed to adapt and refine the curriculum, expand across institutions and specialties, and explore long-term applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Karla Lindquist

REFERENCES

- Bischof RO, Plumb J, Nash DB. Administrative and health policy training for residents. Hospital Prac. 1996; 15:93–100.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Core Program Requirements (Residency). 2023.

- Cozzi N, Jarou Z, Rodos A, Stark N, Sarker A, Thomas Y, et al. Business and Administrative Curriculum for Emergency Medicine Residents: A National Needs Assessment. EM Resident. 2021; 48(4).

- Tupesis JP, Lin J, Nicks B, et al. Leadership Matters: Needs Assessment and Framework for the International Federation for Emergency Medicine Administrative Leadership Curriculum. AEM Educ and Training. 2021; 5(3):e10515.

- Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015.

- Falvo T, McKniff S, Smolin G, Vega D, Amsterdam JT. The Business of Emergency Medicine: A Nonclinical Curriculum Proposal for Emergency Medicine Residency Programs. Acad Emerg Med. 2009; 16(9):900-907.

- Zarrabi B, Burce KK, Seal SM, Lifchez SD, Redett RJ, Frick KD, et al. Business Education for Plastic Surgeons: A Systematic Review, Development, and Implementation of a Business Principles Curriculum in a Residency Program. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017; 139(5):1263-1271.

- Mizell JS, Berry KS, Kimbrough MK, Bentley FR, Clardy JA, Turnage RH. Money Matters: A Resident Curriculum for Financial Management. J Surg Res. 2014; 192(2):348-355.

- Patel R, Rhee K, Barone J, Elsamra SE. Business Education for Residents: Results of a Pilot Business Course at a Urology Residency Program. Urol Pract. 2018; 5(2):107-112.

- Caretta-Weyer H. Transition to Practice: A Novel Life Skills Curriculum for Emergency Medicine Residents. West J Emerg Med. 2019; 20(1):100-104.

- Salib S, Moreno A. Good-Bye and Good Luck: Teaching Residents the Business of Medicine After Residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2015; 7(3):338-340.

- Shappell E, Ahn J, Park YS, McKillip R, Ernst M, Pirotte M, Tekian A. Affective, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes from a resident personal finance curriculum pilot project. AEM Education & Training. 2021; 5(3):e10619.

- Stein MK, Kelly JD, Useem M, Donegan DJ, Levin LS. Training Surgery Residents to Be Leaders: Construction of a Resident Leadership Curriculum. Plast Reconst. 2022; 149(3):765-771.

- DeSimone AK, Jhala K, Osayande DE, Bay CP, Seltzer SE, Matalon SA. Think Like an MBA: Development, Implementation, and Evaluation of an Academic Radiology Business Series (ARBS) for Radiology Trainees. Acad Radiol. 2023.

- Poon E, Bissonnette P, Sedighi S, MacNevin W, Kulkarni K. Improving Financial Literacy Using the Medical Mini-MBA at a Canadian Medical School. Cureus. 2022; 14(6): e25595.

- Holak EJ, Kaslow O, Pagel P. Facilitating the transition to practice: A weekend retreat curriculum for business-of-medicine education of United States anesthesiology residents. J Anesth. 2010; 24(5):807-10.

- Jones K, Lebron RA, Mangram A, Dunn E. Practice management education during surgical residency. Am J Surg. 2008; 196(6):878-81.

- Sarker A, Jarou Z, Cozzi N, et al. Which Topics Should Be Included in a Business and Administrative Curriculum for Emergency Medicine Residents? Presented at the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting (virtual-only due to COVID-19 pandemic) on May 13, 2020.

- Adams NE. Bloom’s Taxonomy of Cognitive Learning Objectives. J Med Libr Assoc. 2015; 103(3):152-153.

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of Physician Self-Assessment Compared with Observed Measures of Competence: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2006; 296(9):1094-102.