Introduction

A 50-year-old female with a past medical history notable for opioid and alcohol use disorder, chronic hepatitis C, microcytic anemia, and complicated alcohol withdrawal presented to the emergency department of a Level I trauma center after being found by medics unresponsive outside in a snowbank. Initially, she had pinpoint pupils and was given 2 mg of intramuscular naloxone with immediate improvement in mentation. She was combative with paramedics and hospital staff, initial vitals were notable for a rectal temperature of 88.7°F, and the remainder of vitals were within normal limits with blood pressure at 122/89. The patient was minimally interactive during examination, though no focal neurologic deficits were noted. The patient was very cold to the touch and was quickly wrapped in warm blankets and given a warm water bath, with warmed intravenous fluids initiated. Glucose was 177. The initial differential included opioid overdose, hypoglycemia, alcohol withdrawal seizure, and hypothermia. Less concern was given for potential head injury, or cardiac or respiratory compromise, as the patient's vitals were initially within normal limits save for her temperature as no obvious injuries or tenderness were noted.

Diagnosis and Management

Initially, only basic blood work and an electrocardiogram were obtained, which were notable for a creatinine of 1.6 and sinus bradycardia with rate of 54 beats per minute with QTc of 489 ms. During the rewarming process, the patient's temperature approached normothermia after multiple hours, though she became hypotensive to around 95/55 despite multiple warmed fluid boluses. She ultimately received 3L of warmed normal saline, with a BP nadir of 86/53. The patient continued to be somnolent but rousable, oriented to person, place, and time, with no neurologic deficits or respiratory depression.

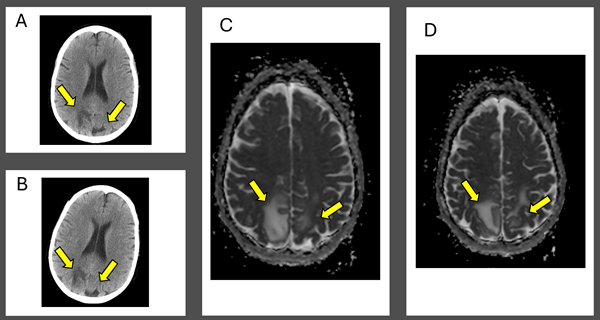

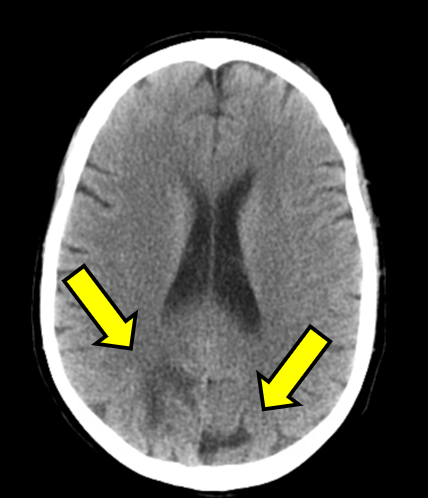

At this point, further workup was initiated: complete metabolic panel, magnesium, phosphorous, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level, ethanol, urinalysis (UA), and urine drug screen (UDS) were obtained, which were notable for improved creatinine of 1.0, calcium of 7.8, mildly decreased TSH of 0.384, nitrite positive UA, and UDS positive for barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and opiates. Non-contrast head CT demonstrated bilateral vasogenic edema in the posterior parietal lobes read as concerning for posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES; see Figure 1A). The patient was admitted after consultation with neurology for observation and an MRI.

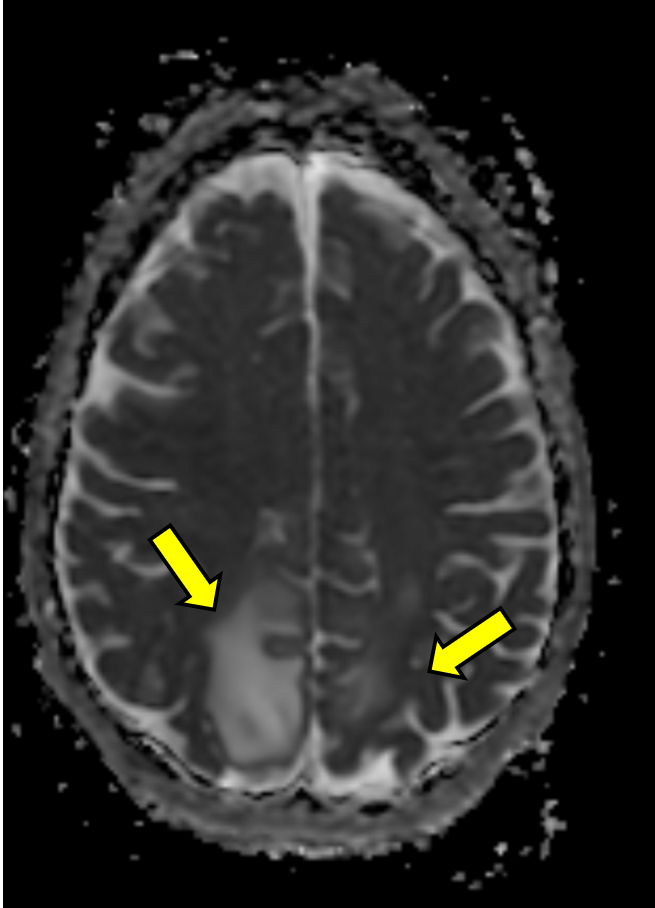

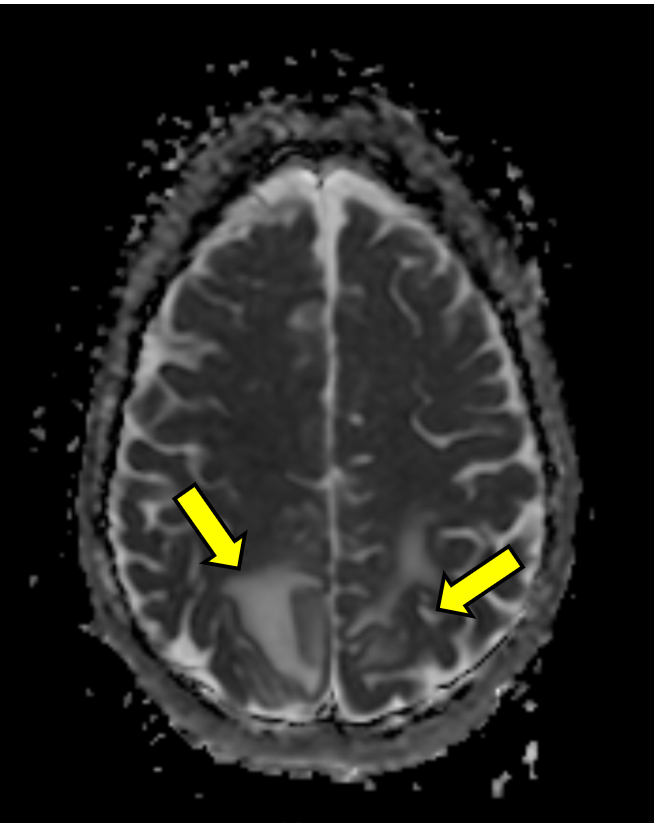

A few hours after admission she ultimately eloped during shift change. She returned to the same ED the next day after being found unresponsive outside again, was given Narcan en route as well as in the ED for bradypnea, and ultimately started on a naloxone drip, though she remained saturating well on room air. The initial temperature was 97.8°F and the initial BP was 121/83. Repeat head CT demonstrated the same vasogenic edema as seen previously (see Figure 1B). The patient was admitted again and remained normotensive. MRI with and without contrast demonstrated expansile T2/FLAIR hyperintense signal in the posterior frontal and parietal lobes, favored to be PRES (see Figure 1C and D).

The next day the patient was weaned off her naloxone drip and maintained good respiratory effort and normal BP. The patient was started on levetiracetam 500 mg twice per day and became insistent that she be discharged. She was sent home with outpatient follow-up, though was ultimately lost to follow-up.

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) was first described in 1996 by Hinchey et al in the context of patients with acute hypertension and in more than 50% of the included patients, renal impairment.1 Traditionally it has been described as presenting with altered mentation, visual disturbances, and seizures, usually in the setting of hypertension with systolic pressures reported in the literature between 150 and 190 mm Hg.2 PRES in the setting of opioid use has been reported in the literature, both among patients with opioid use disorder and among patients receiving narcotics during surgery.3,4,5 Among these cases patients were either hypertensive, normotensive, or did not have mention of the patient's BP. There is a case of pediatric methadone overdose in which the patient presented hypoxic and hypotensive, and was later found to have both PRES and acute cerebellitis.6 No other case to date has demonstrated PRES in the setting of significant hypothermia and concomitant opioid overdose.

PRES in general is a presentation emergency physicians should be familiar with, as prompt treatment has been associated with decreased neurologic sequelae.7 Treatment is generally focused on managing the seizures and hypertension that traditionally accompanies this disease presentation, through the use of benzodiazepines and calcium channel blockers for instance. Multiple theories exist for the pathophysiology of PRES, all involving endothelial dysfunction, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, and vasogenic edema. In the above case, it is likely the combined use of fentanyl and significant hypothermia and hypotension, perhaps with other illicit substances, led to the ultimate vasogenic edema noted on imaging.

Figure 1: Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Demonstrating Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) Figure Caption: Initial (A) and next-day (B) CT imaging of concerning for PRES, with bilateral parietal vasogenic edema noted. MRI demonstrated expansile T2/FLAIR hyperintense signal in the posterior frontal and parietal lobes, favored to be PRES (C and D). Arrows correspond to areas of interest.

A

B

Initial (A) and next-day (B) CT imaging of concerning for PRES, with bilateral parietal vasogenic edema noted. MRI demonstrated expansile T2/FLAIR hyperintense signal in the posterior frontal and parietal lobes, favored to be PRES (C and D). Arrows correspond to areas of interest.

C

D

Teaching Points:

- Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) is a neurologic disorder that traditionally presents with altered mental status, visual disturbances, headaches, and seizures in the setting of hypertension, though cases such as the one in this article demonstrate PRES can be associated with opioid use and present in the setting of hypotension and hypothermia.

- Treatment of PRES should focus on the management of the life-threatening aspects of the disease, including BP management and treatment of seizures with traditional measures such as benzodiazepines and calcium channel blocks.

- In the case of PRES with associated hypothermia, hypotension, and opioid overdose, rewarming measures including warmed intravenous fluids and the use of opioid reversal agents titrated to control respiratory depression should all be utilized.

References

- Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):494-500.

- Zelaya JE, Al-Khoury L. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed May 28, 2025.

- Najaf M. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy in Opiate Toxicity. J Radiol Clin Imaging. 2022;5(4):47-49.

- Sadeghi A, Bakhshandeh Moghadam I, Hekmatdoost A, Salehi N, Zali MR. A case of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography after anesthesia. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2022;15(2):179-183.

- Eran A, Barak M. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome after combined general and spinal anesthesia with intrathecal morphine. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(2):609-612.

- Salloum S, Reyes I, Ey E, Mayne D, White K. Acute Cerebellitis and Atypical Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome Associated with Methadone Intoxication. Neuropediatrics. 2020;51(6):421-424.

- Liman TG, Siebert E, Endres M. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32(1):25-35.