A 56-year-old male with a history of Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia presented to the emergency department for altered mental status, fever, and headache for the past few days.

The patient was initially seen at an outside clinic, where he was found to have mild leukocytosis but otherwise unremarkable workup. Per the patient's wife, he had become increasingly altered. During the ED visit, the patient was found to be febrile at 102°F despite administration of antipyretics, ondansetron, and broad-spectrum antibiotics (ceftriaxone 2 g IV and ampicillin 2 g IV and vancomycin 2 g IV). Altered mental status labs were ordered, including CBC, CMP, TSH, ammonia level, salicylate level, alcohol level, acetaminophen level, urinalysis, urine drug screen, blood cultures, lactic acid, creatinine kinase, COVID/flu/RSV. Additional tests included EKG, chest x-ray, CT head without contrast. Labs were notable for hypokalemia at 2.9 and a creatinine kinase of 640, but otherwise showed no acute abnormalities contributing to his presentation.

A lumbar puncture was attempted unsuccessfully, and CT head showed mild biparietal cerebral atrophy with no acute intracranial findings. The patient was admitted to the medicine floor.

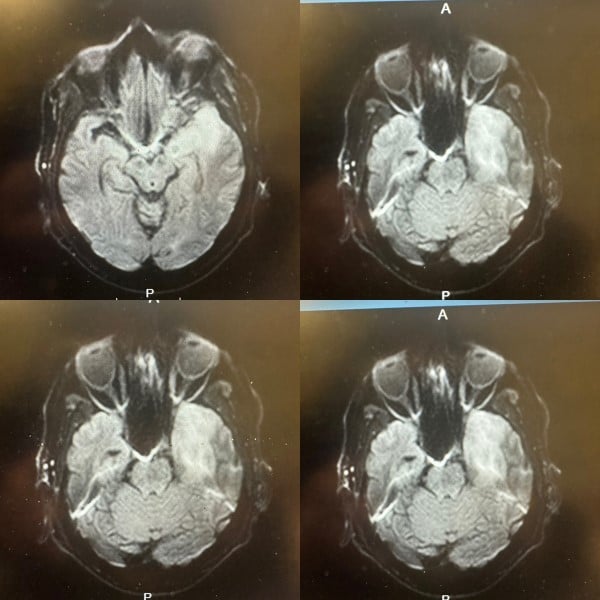

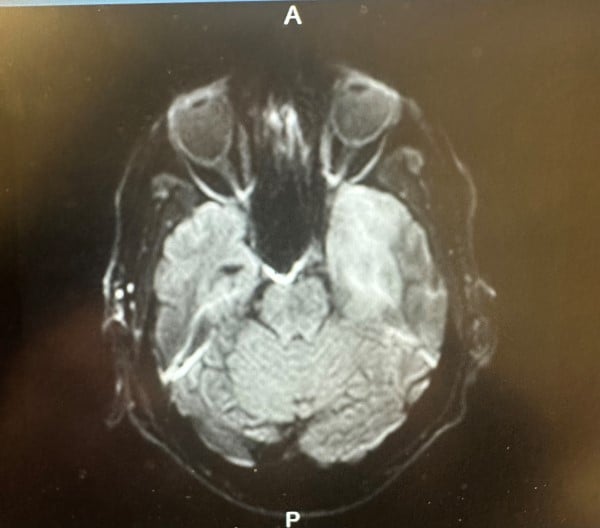

On admission, the patient was found to be somnolent, oriented only to person, with expressive aphasia. A lumbar puncture was ordered, with a meningitis panel and HSV serology. HSV-1 serology returned positive and CSF showed increased cell count, increased glucose and increased CSF protein. MRI was performed at this time, which showed mild abnormal FLAIR hyperintensity and restricted diffusion within the left medial temporal lobe cortex. Given high suspicion for HSV encephalitis, an acyclovir regimen was started.

The patient continued to have waxing and waning presentation of altered mental status and expressive aphasia. Headaches were continuously treated with IV acetaminophen and dexamethasone.

EPIDEMIOLOGY/CLINICAL FEATURES

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) encephalitis is the most common cause of sporadic fatal encephalitis worldwide. The clinical syndrome is often characterized by the rapid onset of fever, headache, seizures, focal neurologic signs, and impaired consciousness.1 This patient had presented with fever, headache, and altered mental status for the days prior to his ED admission. HSV-1 encephalitis is a devastating disease with significant morbidity and mortality, despite available antiviral therapy.

Other clinical features can be marked by acute (<1 week in duration) and include focal cranial nerve deficits, hemiparesis, dysphasia, aphasia, or ataxia.2 More than 90 percent of patients will have one of the above symptoms plus fever.2 Other associated neurologic symptoms include urinary and fecal incontinence, aseptic meningitis, localized dermatomal rashes, and Guillain-Barré syndrome.3 During the patient's ICU stay, he did require an external male catheter after a few days, as he had become incontinent. The patient also exhibited diminished comprehension, paraphasic spontaneous speech, impaired memory, and loss of emotional control—which are common sequelae of the disease process.4 The patient would repeatedly forget the names of the members of his health care team, despite their continuity throughout his hospital stay. The patient exhibited alternating periods of sadness and extreme happiness, suggesting a potential loss of emotional regulation.

Evaluation/Diagnosis

- Lumbar puncture is indicated for cerebrospinal fluid analysis and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for HSV in any patient with encephalitis. The detection of herpes simplex virus DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is considered the gold standard for establishing the diagnosis. Examination of the CSF typically shows a lymphocytic pleocytosis with counts ranging from 10 to 400 cells/microL, an elevated protein, and an increased number of erythrocytes (in 84 percent of patients).5 This was consistent with this patient’s laboratory findings; however, this patient did not have a high number of erythrocytes. Nucleated cells including lymphocytes were significantly elevated as was the CSF protein.

- (MRI) brain is also used to assess signs of temporal lobe involvement, which supported the diagnosis. Brain MRI would also eliminate other alternative causes of mental status changes, such as brain abscess.

- Brain biopsy is not generally needed to establish diagnosis but should be considered if the patient clinically deteriorates on appropriate therapies.

Treatment

For patients with suspected HSV encephalitis, the recommended empiric therapy is acyclovir (10 mg/kg intravenous IV every 8 hours).2 Treatment should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is considered, because delays in treatment can lead to significant neurologic sequelae. If the evaluation supports the diagnosis of HSV encephalitis, treatment should be continued for 14 to 21 days.2

Prognosis

Because acyclovir is effective in halting viral replication, early therapy can prevent extensive replication and further CNS damage. However, even with early administration of therapy after onset of disease, nearly two-thirds of survivors will have significant neurologic deficits.6 Mortality may still be as high as 20-30%, even with appropriate treatment.2 This patient was eventually discharged to a neurorehabilitation facility following his course of HSV encephalitis and treatment. The patient was discharged in stable condition with residual anterograde amnesia and expressive aphasia.

References

- Hanley DF, Johnson RT, Whitley RJ. Yes, brain biopsy should be a prerequisite for herpes simplex encephalitis treatment. Arch Neurol 1987; 44:1289

- Levitz RE. Herpes simplex encephalitis: a review. Heart Lung 1998; 27:209.

- Tyler KL, Tedder DG, Yamamoto LJ, et al. Recurrent brainstem encephalitis associated with herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA in cerebrospinal fluid. Neurology 1995; 45:2246.

- Hart J, Sloan Berndt R, Caramazza A. Category-specific naming deficit following cerebral infarction. Nature. 1985;316:439-440.

- Nahmias AJ, Whitley RJ, Visintine AN, et al. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis: laboratory evaluations and their diagnostic significance. J Infect Dis. 1982; 145:829.

- Whitley RJ, Kimberlin DW. Herpes simplex: Encephalitis children and adults. Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Disease. 2005; 1:17-23.