Unlike in the adult population, back pain is an uncommon chief complaint in the pediatric population, representing 0.4% of all emergency department encounters in one study.1

It is estimated that up to 77% of back pain presentations in the pediatric population are due to benign causes.2 These benign causes include muscle strains, back contusions, and sports-related injuries. However, there are more serious, but less common, causes to be considered in adolescents with back pain, especially when patients present with fever and labs point to a possible infection.

Epidural abscess is a rare but serious condition that should be considered in patients with fever and localized back pain. Failure to appropriately diagnose and treat epidural abscess in a timely manner can cause significant irreversible neurological deficits.3

Case Report

A previously healthy 13-year-old male presented to the emergency department with right flank pain. The pain had started the night prior, initially located between his shoulder blades, and had migrated to the right flank by the time of presentation. The pain was constant but worsened by inspiration. He also had a home temperature of 100.2°F. He had taken 200 mg of ibuprofen overnight without relief. He denied trauma or previous similar episodes of flank pain. He also denied nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dysuria, or hematuria.

His triage vitals were significant for an oral temperature of 100°F, heart rate of 121, and a respiratory rate of 22. Blood pressure was normal at 123/61, and the patient had a peripheral oxygen saturation of 100% on room air. His initial exam was significant for right costovertebral angle tenderness and mild right lower quadrant abdominal tenderness.

His initial workup included a CBC showing mild leukocytosis at 13,500/mm3 with a neutrophilic predominance, an unremarkable complete metabolic panel, and a urinalysis that only showed trace protein and no hematuria. COVID and influenza PCR tests were negative, although a Covid-19 spike antibody test was positive, indicating prior infection. An initial abdominal X-ray and abdominal ultrasound did not show any abnormalities. At this point, the patient was admitted to the hospital for further diagnostic workup. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast showed only mild bilateral atelectasis and possible infiltrates at lung bases. It was negative for nephrolithiasis or appendicitis.

At this point, a presumed diagnosis of community acquired pneumonia was made, and his back pain was ascribed to general myalgias in the setting of his pneumonia. The plan was to discharge the patient on amoxicillin and azithromycin with outpatient follow-up. However, the patient’s pain worsened in his back and right flank. He also remained tachycardic and spiked a fever to 104.8°F so he remained in the hospital for observation. He later developed nausea and had 4 episodes of non-bloody emesis. On day 2 of hospitalization, the overnight team noted moderate tenderness to palpation of the spine from the upper thoracic to the sacral area. At this point, blood cultures and an MRI of the spine were ordered.

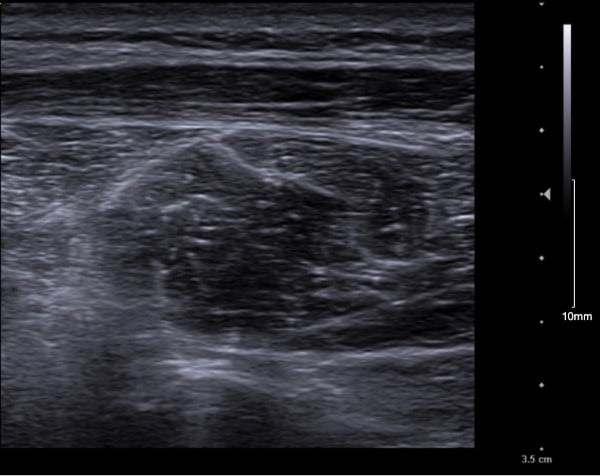

The MRI findings were significant for a moderate-sized epidural abscess extending from the T3 to T10 level, along with a paraspinal soft tissue abscess near the spinal canal at the T10 level. The patient then underwent an aspiration procedure with interventional radiology where a 10 Fr drain was placed under ultrasound guidance at the soft tissue abscess site. Neurosurgery was consulted, and they did not recommend surgical intervention in the absence of neurological deficits.

Upon recognition of the paraspinal and epidural abscess, he was started on ceftriaxone and vancomycin. Blood cultures came back positive for MSSA bacteremia, which was also consistent with abscess drain cultures. The patient was switched to IV nafcillin after day 4 of hospitalization.

Infectious disease was consulted and discovered that the patient had a distant history of a submental abscess 5 months ago, which was treated with antibiotics only. A follow-up echocardiogram did not show any vegetation or other sources of infection. The patient remained in the hospital for 8 days on IV antibiotics and was discharged with a PICC line for 6 more weeks of IV nafcillin.

Discussion

Pediatric spinal epidural abscess is an extremely rare infection of the central nervous system that can have significant neurologic sequelae if not diagnosed and treated in a timely manner. Its prevalence is estimated to be 0.6-1.5 per 10,000 admissions.4 This condition is characterized by pus in the space between the dura and the periosteum of the vertebrae. The presenting symptoms are commonly nonspecific, which makes spinal epidural abscess a challenging diagnosis that requires a high index of suspicion. The classic triad of symptoms is fever, localized back pain, and neurological deficits. Although highly specific, patients rarely present with all three symptoms at the initial encounter, and this triad is found only in about 13% of patients with a spinal epidural abscess.5 Neurological deficits appear later in the course of the disease if not treated appropriately. It is important to have a high clinical suspicion for epidural abscess in certain patients, even in the absence of neurological symptoms.

Some of the risk factors associated with spinal epidural abscess are diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, immunodeficiency syndrome, IV drug use, and malignancy.6 Since these risk factors are more predominant in the adult population, most cases of epidural abscesses occur in adults. Spinal epidural abscess occurrence in the pediatric population is not only extremely rare, but also the clinical presentation can be very nonspecific. In our patient, he initially complained of right flank pain in the emergency department. Initial concerns included pyelonephritis, urinary tract infection, or nephrolithiasis, although his unremarkable urinalysis made these diagnoses less likely. Because he had leukocytosis and a fever, an infectious etiology was suspected, and the patient was admitted for further evaluation.

Our patient did not have any predisposing risk factors or neurological complaints. However, he did have a history of submental abscess formation 5 months prior. There are laboratory studies that can increase the clinical suspicion for epidural abscess, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). In a meta-analysis, it was found that ESR was elevated in 94% of patients diagnosed with epidural abscess.7 Although we did not have an ESR available for our patient, his CRP was elevated at 181.2mg/L.

The most common causative agent in epidural abscess is Staphylococcus Aureus. The blood cultures and abscess cultures of our patient were both positive for Methicillin Sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus (MSSA). The goal of management is early decompression of the site of maximal compression to prevent neurologic deficits as well as isolating the causative agent. The decision for medical versus surgical management is somewhat controversial. One study found that more than 40% of patients who were treated medically later required surgical management due to failure of treatment.8 Factors associated with medical treatment failure include: diabetes, CRP greater than 115 mg/L, white blood count (WBC) greater than 12,500/mm,3 and bacteremia. Our patient had an elevated CRP, WBC, as well as bacteremia, which all made medical management unlikely to be successful. Consequently, he underwent drainage of his abscess by interventional radiology, and was started on 4-6 weeks of antibiotic treatment. On his follow-up visits with the infectious disease clinic, he was found to be neurologically intact and clinically improving.

Figure 1. T2 weighted sagittal MRI image with epidural fluid collection from the T3 to T10 level at the dorsal aspect of the spinal canal showing epidural abscess along with moderate compression of the thoracic spinal cord.

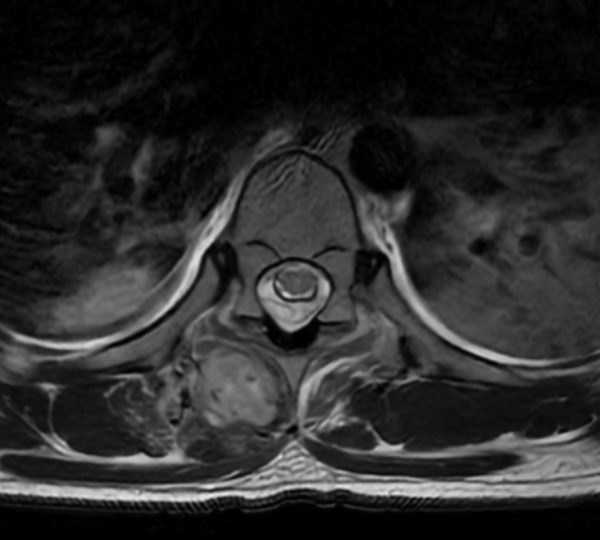

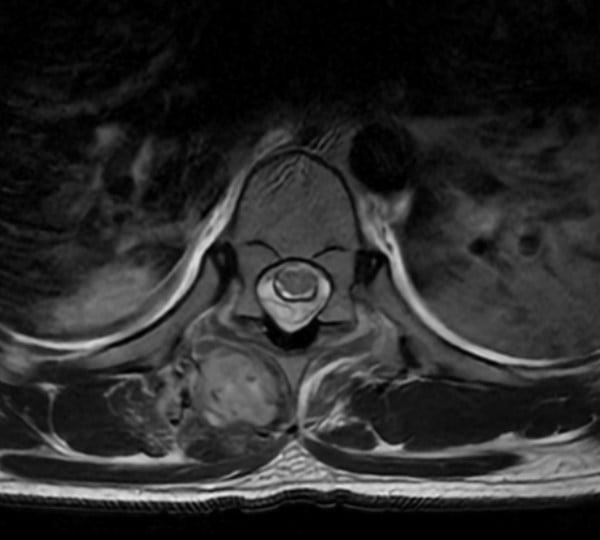

Figure 2. T2 weighted axial MRI image at the level of T10 showing the epidural abscess with effacement of cerebrospinal fluid around the spinal cord (A) along with a soft tissue paraspinal muscle abscess measuring 4.5cm x 2cm x 2cm (B).

Figure 3. Paraspinal abscess under ultrasound showing mixed echogenicity within a well-defined abscess capsule.

References

- Selbest SM, Lavelle JM, Soyupak SK, Markowitz RI. Back pain in children who present to the emergency department. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1999;38(7):401-406.

- Brooks TM, Friedman LM, Silvis RM, Lerer T, Milewski MD. Back Pain in a Pediatric Emergency Department: Etiology and Evaluation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(1):e1-e6. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000798

- Houston R, Gagliardo C, Vassallo S, Wynne PJ, Mazzola CA. Spinal Epidural Abscess in Children: Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2019;126:453-460. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.294

- Auletta JJ, John CC. Spinal epidural abscesses in children: a 15-year experience and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(1):9-16. doi:10.1086/317527

- Davis DP, Wold RM, Patel RJ, et al. The clinical presentation and impact of diagnostic delays on emergency department patients with spinal epidural abscess. J Emerg Med. 2004;26(3):285-291. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2003.11.013

- Chao D, Nanda A. Spinal Epidural Abscess: A Diagnostic Challenge. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(7):1341. Accessed December 19, 2021. www.aafp.org/afpAMERICANFAMILYPHYSICIAN1341

- Reihsaus E, Waldbaur H, Seeling W. Spinal epidural abscess: A meta-analysis of 915 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2000;23(4):175-204. doi:10.1007/PL00011954

- Patel AR, Alton TB, Bransford RJ, Lee MJ, Bellabarba CB, Chapman JR. Spinal epidural abscesses: risk factors, medical versus surgical management, a retrospective review of 128 cases. Spine J. 2014;14:326-330. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2013.10.046