“This is Ambulance 80. We are currently en route to your facility with a 72-year-old male who sustained a 2-story fall”¦”

To an experienced provider, this may sound like the beginning of a familiar story. To a novice in emergency medicine, however, this can be an exciting case with many high-yield learning points. What if there was a way to expose interested medical students to scenarios like this outside of the emergency department environment? What if there was a way to prepare future providers for complicated patients and evaluate their performance to improve subsequent care? This is what SIMWars is all about.

WHAT IS SIMWARS?

SIMWars is an educational competition in which teams face off in scripted scenarios to demonstrate their clinical skills, teamwork, communication, and problem-solving abilities. Created by Yasuharu Okuda, MD, FACEP, Andy Godwin, MD, FACEP, and Scott Weingart, MD, FACEP, in 2007, the SIMWars competition usually is geared toward residents, but has recently expanded to include teams of medical students.2 The cases are created to give the competitors and audience members an entertaining and educational experience by establishing a timed, interactive clinical scenario, followed by a debrief of the participants' clinical actions and team dynamics.

GETTING STARTED

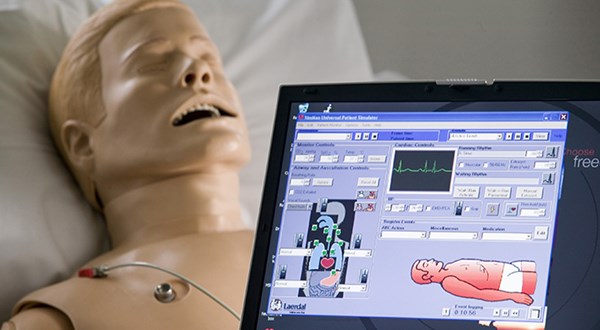

One of the most important components of a successful competition is access to a simulation lab and becoming familiar with the simulation mannequin. The differences between the plastic patient and a real patient are sometimes overlooked, and knowing how to suspend reality and buy into the idea that this plastic person is a real patient is crucial to success in the competition. Something as simple as how the heart and lungs sound, or how firmly to press down when checking for a pulse is different on the mannequin compared to a live person and requires practice for successful performance in the scenario.

If your medical school doesn't have an EM residency program or a simulation fellowship, have no fear- you can still participate. Most schools have simulation centers to prepare their students for clinical skills examinations and third-year clerkships. These centers are often happy to accommodate teams by providing the place and tools to practice. Ideally, practice essentials would include a mannequin, airway equipment, a heart monitor with defibrillation capability, equipment to measure and monitor vitals, and large screens so teams can observe changes in the patient's condition as the case progresses.

The simulation center coordinator will likely have cases that can serve as practice scenarios. Cases can also be found in online FOAMed resources, adapted from EMRA's Top Clinical Problems book (that comes free with your membership), or created by supervising faculty. Look for a few SIMWars cases that include “critical action checklists,” as competitions often use these as judgment criteria for their cases. Review cases with common chief complaints and broad differentials so your team can consider and learn about multiple diagnoses.

Once you have your practice space, equipment, and cases, you will want some help from an experienced provider. An emergency medicine physician can serve as a team coach, giving feedback and teaching from personal experience. Try reaching out to your emergency department to garner support. If your school is not associated with a hospital, reach out to a local hospital's department or go through your alumni center. Faculty members at academic institutions are generally eager to foster students' love for emergency medicine, and many are already familiar with SIMWars or some variation of it.

The next step is to build a team. The competition rules will dictate team size, which may force you to figure out how to choose the strongest team. Some groups may want to divide applicants into teams prior to the event and hold a school-wide competition to choose the competition group. Other groups may elect to select teammates on a first come-first serve basis. Overall, a good strategy is to select students whose combined attributes make a complete and strong team. Consider leadership, medical knowledge, and prior clinical experience, since each case will be different and require diverse skills. If space is available, some schools may also train enough competitors for two teams. It is a good idea to include as many people as possible in the training process, including junior members, so that everyone can learn from the experience. Remember, the more students involved form an earlier point, the more senior students will be familiar with the competition. Be sure to take in account each team member's availability and additional responsibilities - even the smartest team member is of no use if they cannot attend practice.

PRACTICE

With the team assembled and practice facility secured, the team is ready to get down to business. Peruse the competition guidelines again, paying special attention for any unique rules. For example, the usage of faculty lifelines and clinical decision cards are two factors that are often subject to variation. Consult prior participants about cases they encountered to get an idea of what could be fair game. Determine how teams are scored. Is scoring completed by physician judges, or by the entire audience? Is there a scorecard that the judges will be using, and if so, can you get a copy to help guide practice? This will take a lot of time and maybe some sacrifices for some people, but you want as many participants to be present at each practice as possible. Teams perform better the more they practice together.3

There are many ways to approach practice. Some teams prefer verbally discussing the case prior to practicing on the mannequin; this allows team members the ability to clarify key history items to ask the patient as well as which labs, medications, and imaging studies to order. Once the team moves on to the mannequin, they can focus on building communication and teamwork in an environment similar to the competition. An alternative strategy is to begin by running through the case with no knowledge of the scenario and reviewing all previously mentioned points during the conclusion. This method prepares members to think on their feet and more closely simulates the experience of the competition, which may help prepare the team for the actual feeling when the big day comes. It is also advisable to set aside a designated skills day for the team to practice critical procedures under low-stress conditions. Some competitions may ask you to perform certain procedures as indicated by the scenario, while others may simply require that you describe how you would set up and complete the procedure.

TIPS FOR COMPETITION DAY

- Assign specific roles to team members, and make sure they have time to practice a few times in this role. Team dynamics take dedication and practice to learn.

- When a patient starts to deteriorate, go back to your ABCs. Figure out what is compromising their airway, breathing, or circulation.

- Talk to each other. Decide on your differential, workup, and management together. You are part of a team for a reason.

- Close the communication loop. Make sure you are speaking directly to someone when giving an order, and that they check back that the order is correct and complete. You may be working with nurses or other team members on competition day that you have not met prior to the event.

- Huddle often to summarize what you know and what you are thinking. This ensures everyone is on the same page, and gives someone a chance to speak up if they think the team is forgetting something.

- After the scenario, decide what went well, and what did not go so well. Self-reflection helps you grow as a team and an individual, and tells you what you could change or keep doing next time.

- Recap after some time has passed after the competition. Critique your team like you would critique another team. Try to incorporate objective measures into the team's performance to identify areas for potential improvement.

- Listen to what the judges say. If you advance to the next round, you can implement this advice immediately. If you do not advance, this advice is invaluable for the next competition.

- Take note of the cases used in the competition. Was there one in particular that caused significantly more difficulty? Use this information to help guide further practice.

- Celebrate. Whether you take home the gold or not, it was a great experience and everyone learned something.

CONCLUSION

SIMWars is not just a competition. It is an all-encompassing, exhilarating experience that expands your limits, grows your medical knowledge, and demonstrates the value of teamwork and communication. Most of all, it prepares you to handle real patients that you may encounter. So, the next time that you see a familiar presentation in your local ED, you will be ready and confident to provide excellent care.

This is a guide based on our experiences in SIMWars, but this is by no means intended to be an exhaustive overview of competition advice. Let us know about your experiences. Do you have any other tips about training that went well or training that did not go well? How would you build a team? Reach out to the EMRA Simulation Division- we would love to hear from you!

References

- Dong C, Clapper T, Szyld D. A qualitative descriptive study of SIMWars as a meaningful instructional tool. Int J Med Educ. 2013;4:139-145.

- Jacobson L, Okuda Y, Godwin SA. SimWars Simulation Case Book: Emergency Medicine. 1st ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2015.

- Helsen W, Starkes J, Hodges N. Team sports and the theory of deliberate practice. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1998;20(1):12-34.