INTRODUCTION

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) in young, otherwise healthy individuals without underlying cardiovascular disease represents one of the most challenging scenarios in emergency resuscitation. In this patient group, the most common causes are inherited channelopathies, among which Brugada syndrome is a rare but critically important diagnosis. The hallmark ECG finding of Brugada type 1, a coved-type ST-segment elevation in leads V1–V2 may be transient, only manifesting under certain triggers such as fever, increased vagal tone, or sodium channel blocker use. Notably, sudden cardiac arrest can be the first, and only manifestation of this syndrome.

Accurate diagnosis and timely emergency management are vital for survival. After achieving return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), post-resuscitation care—particularly targeted temperature management (TTM)—has been shown to reduce neurological sequelae and improve outcomes. However, in many intensive care units in middle-income countries, the implementation of TTM remains limited due to the lack of specialized equipment and adequately trained personnel.

We present a representative case: a 39-year-old man with no past medical history experienced cardiac arrest after lunch, was successfully defibrillated, and demonstrated a classic Brugada type 1 pattern on ECG. However, TTM could not be implemented due to practical constraints. This case highlights the importance of early recognition of Brugada syndrome in emergency settings and underscores the systemic limitations in post-arrest care, particularly in resource-limited settings.

CASE PRESENTATION

A previously healthy 39-year-old man with no known medical conditions was brought to the emergency department (ED) after experiencing a witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) approximately 15 minutes after finishing a meal. According to family members, he suddenly collapsed without preceding symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, or palpitations. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was initiated immediately. Emergency medical services (EMS) arrived within minutes, documented ventricular fibrillation (VF) on the monitor, and delivered two defibrillation shocks. The patient achieved return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) en route to the hospital.

On ED arrival, the patient was comatose (GCS 3), intubated, and mechanically ventilated. Initial vital signs were: blood pressure 105/70 mmHg, heart rate 88 bpm, SpO₂ 98% on mechanical ventilation, and core temperature 37.8°C. Physical examination revealed no focal neurological deficits or signs of trauma. Pupils were equal and reactive. Cardiac and pulmonary examinations were unremarkable.

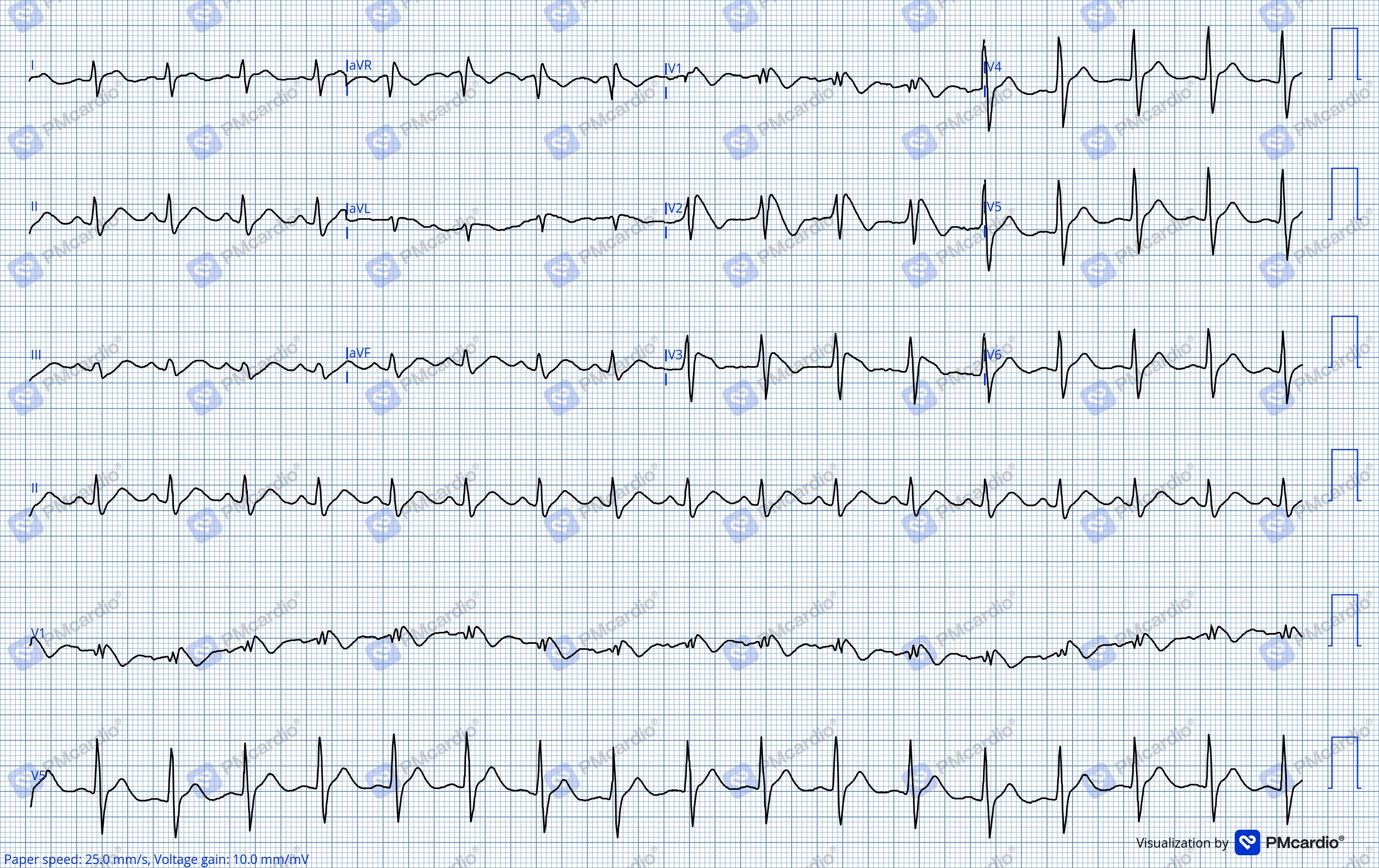

A 12-lead ECG obtained immediately post-ROSC showed coved ST-segment elevation ≥2 mm in leads V1–V2, consistent with a type 1 Brugada pattern. The findings were clearly visible on standard precordial lead placement without the need for high intercostal recordings. There was no QT prolongation, pre-excitation, or other arrhythmias.

Post-resuscitation 12-lead ECG demonstrating type 1 Brugada pattern with coved ST-segment elevation ≥2 mm in leads V1–V2, followed by inverted T waves. The Brugada morphology is clearly visible on standard precordial lead placement without the need for high intercostal recordings.

Laboratory testing revealed normal electrolyte levels, renal function, and cardiac biomarkers. Arterial blood gas analysis showed mild metabolic acidosis (pH 7.32). Point-of-care echocardiography demonstrated normal cardiac chamber size and preserved left ventricular function, with no regional wall motion abnormalities or pericardial effusion. Chest X-ray and non-contrast head CT were unremarkable. No reversible causes of cardiac arrest (e.g., electrolyte disturbance, myocardial infarction, hypoxia) were identified.

As the facility lacked advanced cooling equipment, passive temperature management was implemented along with deep sedation (midazolam and fentanyl), lung-protective ventilation, and close neurological monitoring. The patient remained hemodynamically stable and did not require vasopressor support.

The patient was transferred to a tertiary care center after achieving stable ROSC with initial supportive management. Despite effective post-resuscitation care at the district hospital, the facility lacked resources for targeted temperature management (TTM), advanced neuro-monitoring, and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation—all of which are essential for optimal management in this clinical scenario.

He was therefore urgently referred to a specialized cardiac center for further neurologic evaluation, genetic testing, family screening, and planning for ICD implantation.

CONCLUSION

This case illustrates a classic yet often overlooked clinical manifestation of Brugada syndrome, a dangerous cardiac channelopathy that can lead to ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) as its very first presentation. The post-ROSC electrocardiogram demonstrated coved ST-segment elevation ≥2 mm in leads V1–V2, clearly visible on standard precordial leads without the need for higher placement—meeting the diagnostic criteria for Brugada type 1 pattern as outlined in international guidelines.1 Prompt and accurate recognition of this ECG morphology enabled timely diagnosis and guided appropriate management decisions.

Pathophysiologically, Brugada syndrome results from repolarization abnormalities in the epicardial layer of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT). Mutations in the SCN5A gene reduce inward sodium current (INa), while outward potassium current (Ito) is often enhanced, leading to transmural dispersion of repolarization. This imbalance creates a vulnerable substrate for phase 2 reentry, which triggers premature ventricular contractions and degenerates into ventricular fibrillation. These electrical events can be precipitated by physiological modulators such as fever, vagal tone, or postprandial autonomic shifts—as seen in our patient.2

In the setting of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in a young individual without structural heart disease, differential diagnoses should include:3

- Congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) – usually presents with QTc >480 ms, which was not observed in this case.

- Short QT Syndrome (SQTS) – excluded based on normal QTc interval.

- Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT) – typically exercise-induced, inconsistent with this patient’s rest-related event.

- Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC) – ruled out via echocardiography, which showed no chamber dilation or regional wall motion abnormalities.

Given the Brugada type 1 ECG pattern and the exclusion of other arrhythmic substrates, the diagnosis was established with high confidence.

Following ROSC, post-resuscitation care plays a crucial role in determining neurological outcomes. Targeted Temperature Management (TTM) has been shown to reduce hypoxic brain injury and carries a Class I recommendation in both the AHA 2020 and ERC 2021 guidelines for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest, irrespective of initial rhythm. However, in many resource-limited hospitals, implementation of TTM remains a significant challenge due to the lack of cooling equipment and trained personnel.4 In our case, although TTM could not be applied, alternative neuroprotective strategies such as passive temperature control, deep sedation, lung-protective ventilation, and close neurological monitoring were rigorously pursued—contributing to a favorable functional recovery.

Regarding long-term secondary prevention, survivors of SCA due to Brugada syndrome fall into a very high-risk category for recurrence. According to the 2013 HRS/EHRA/APHRS consensus statement and subsequent updates, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation is a Class I indication in this population. ICDs remain the only therapy with proven mortality benefit; antiarrhythmic drugs such as amiodarone or quinidine have not demonstrated consistent efficacy and may pose additional risks. The patient in our case was referred to a specialized cardiac center for genetic counseling, first-degree family screening, and ICD implantation planning.

This case highlights that even in the absence of ideal interventions such as TTM, a well-structured resuscitation strategy—based on timely ECG recognition and vigilant post-ROSC monitoring—can lead to meaningful clinical recovery. Furthermore, it underscores the urgent need to strengthen front-line electrophysiological diagnostic capabilities, ensure ICD accessibility, and develop robust post-arrest care systems, particularly in middle-income countries.5

Learning Points

- Brugada syndrome should be suspected in young patients with sudden cardiac arrest and no structural heart disease. Prompt recognition of type 1 Brugada ECG pattern post-ROSC is critical for early diagnosis and appropriate management.

- Standard ECG lead placement may suffice to detect Brugada type 1 pattern, but clinicians should be aware that high intercostal lead positioning can improve sensitivity in borderline cases.

- Targeted temperature management (TTM) remains a cornerstone of post-cardiac arrest care but may not be feasible in all settings. In such cases, passive cooling, deep sedation, and neuro-monitoring are reasonable alternatives.

- ICD implantation is a Class I recommendation for secondary prevention in patients with Brugada syndrome who have survived cardiac arrest. No antiarrhythmic drug has been proven effective in this population.

- Systems-level barriers—including limited access to cooling devices, ICDs, and electrophysiology expertise—can delay optimal care. This case highlights the need to strengthen post-arrest care capabilities at regional and district hospitals.

REFERENCES

- Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, Cho Y, Behr ER, Berul C, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS Expert Consensus Statement on the Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Inherited Primary Arrhythmia Syndromes: Document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm. 2013 Dec 1;10(12):1932–63.

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D, et al. Brugada Syndrome: Report of the Second Consensus Conference. Circulation. 2005 Feb 8;111(5):659–70.

- 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death - HRS [Internet]. https://www.hrsonline.org/. [cited 2025 Jun 16].

- Omairi AM, Pandey S. Targeted Temperature Management. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 16].

- Mkoko P, Bahiru E, Ajijola OA, Bonny A, Chin A. Cardiac arrhythmias in low- and middle-income countries. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2020 Apr;10(2):35060–360.