Introduction

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a neurologic emergency frequently encountered in emergency departments and associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Prompt and accurate diagnosis is essential, as SAH often necessitates emergent neurosurgical consultation, blood pressure management, reversal of anticoagulation, and most often admission to intensive care.1 Non-contrast cranial computed tomography (CT) remains the first-line imaging modality in the emergency evaluation of suspected SAH, with a sensitivity close to 100% within the first 3 days of symptom onset.2 Hyperdensity in the subarachnoid spaces—particularly over the cerebral convexities, cisterns, and falx—is classically interpreted as indicative of acute hemorrhage.3 However, in rare cases, this radiographic appearance may be mimicked by non-hemorrhagic etiologies, resulting in what is termed pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage (pSAH). Known causes of pSAH include diffuse cerebral edema, contrast encephalopathy, and inadvertent introduction of radiopaque substances into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).4 While pSAH following iodinated contrast administration is documented, reports involving gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs)—particularly in the context of fluoroscopically guided interventional pain procedures—are exceedingly rare.5-11 We describe a case of a 61-year-old female presenting to the emergency department with acute altered mental status and CT findings suspicious for SAH following a cervical medial branch block performed with gadobutrol.

Case Report

A 61-year-old female with past medical history of cervical spondylosis, hypertension, atrial fibrillation on dabigatran, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and a remote gastric bypass surgery was referred to the interventional pain clinic for management of chronic axial neck pain. Notably, she also had a documented allergy to iodinated contrast agents. Given her response to a prior diagnostic block with 80% relief, she was scheduled for a repeat left C3–C5 medial branch block.

Due to her contrast allergy, gadobutrol was used. Dabigatran was appropriately discontinued 5 days prior to the injection, in accordance with American Society of Regional Anesthesia guidelines for medium-risk procedures,12 and the patient's cardiologist had given clearance to stop anticoagulation for both this procedure and an upcoming gastrointestinal scope.

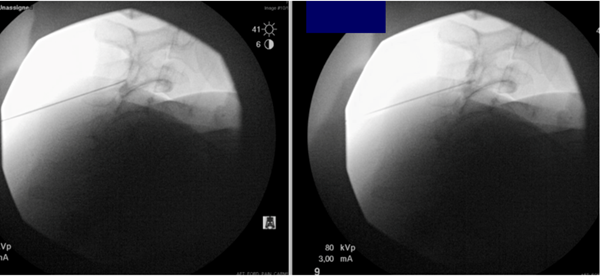

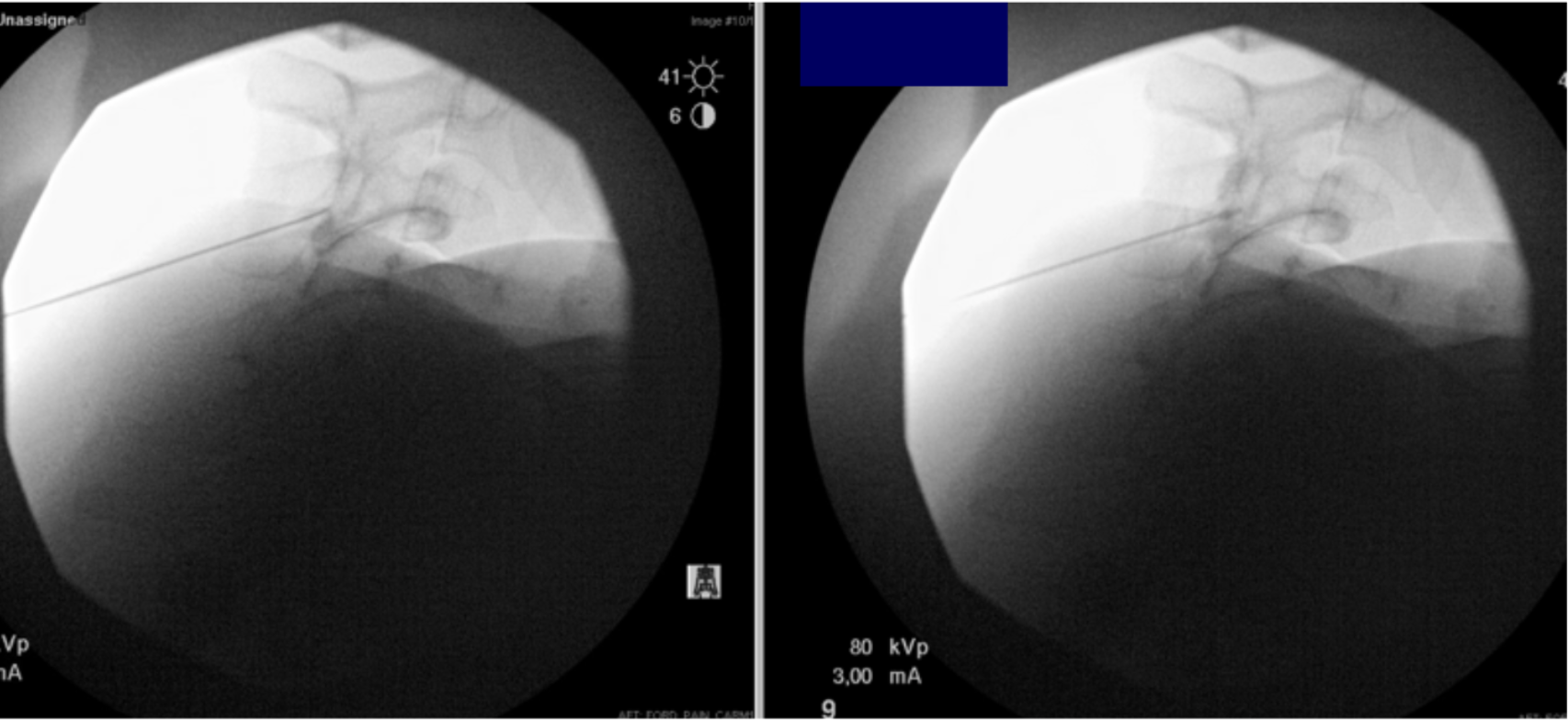

The medial branch block was carried out using fluoroscopic guidance. Gadobutrol was injected at the left C3, C4, and C5 medial branch targets. No vascular uptake was visualized on fluoroscopic examination. The procedure was completed without any immediate complications. Post-procedurally, the patient was observed and noted to be alert, oriented, and conversant. She was cleared for discharge after standing and verbalizing her discharge instructions appropriately.

Approximately 40 minutes later, clinic staff noted the patient had not exited the post-procedure area. The patient was found in another cubicle, disoriented and unresponsive to verbal cues. Vital signs were stable. Glucose was within normal limits. Emergency medical services were alerted for transfer to the nearest emergency department.

Figure 1: Left cervical medial branch block under fluoroscopic guidance using GBCAs

Upon arrival at the emergency department, the patient remained confused and was only oriented to self, scoring a 4 on the NIH Stroke Scale. Initial CT of the head without contrast revealed hyperdensities in the interhemispheric falx and bilateral frontal convexities, raising concern for acute SAH. CT angiography of the head and neck demonstrated no aneurysm or large vessel occlusion, only mild atherosclerosis with less than 50% stenosis of the bilateral internal carotid arteries. Due to recent dabigatran use, idarucizumab was administered for reversal. The patient was admitted for close neurologic monitoring.

Two days later, MRI of the brain revealed sulcal T1 and T2 hyperintensities most prominently over the superior frontoparietal convexities, consistent with evolving subacute SAH. Importantly, there was no associated edema, midline shift, or hydrocephalus. Diffusion-weighted imaging was negative for acute ischemia, and chronic small vessel disease was noted. Given the rapid resolution of clinical symptoms and absence of aneurysm, the findings were most consistent with pSAH secondary to inadvertent gadolinium diffusion into the CSF.

The patient’s mental status improved back to baseline within hours of admission, and she remained hemodynamically and neurologically stable throughout her hospital stay. She was discharged home in normal health after 3 days.

Case Discussion

The use of GBCAs has been documented to rarely cause radiographic findings that mimic diffuse SAH, particularly in high doses or in proximity to CSF pathways.13 This phenomenon, known as pSAH, is a rare but critical diagnostic consideration in patients presenting with acute neurologic changes following neuraxial procedures. Our case further contributes to the limited body of literature describing iatrogenic pSAH following inadvertent contrast diffusion during spinal procedures.

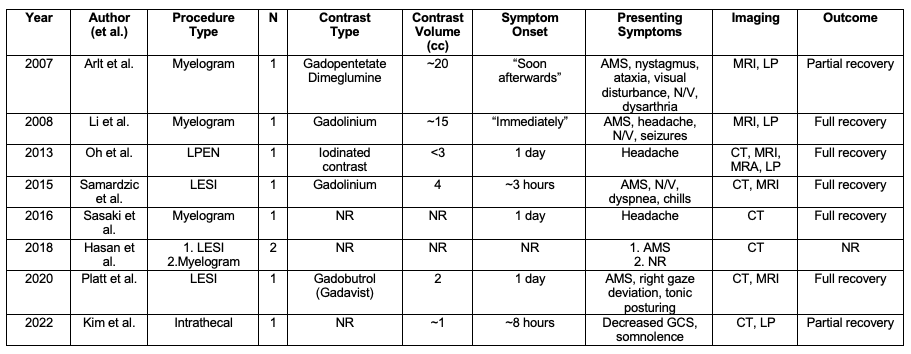

As summarized in Table 1, there are 9 other reported cases of contrast-induced pSAH. Our patient represents a rare case occurring after a cervical medial branch block, with most prior reports describing procedures involving the lumbar spine.5-11 Similar to most previous cases, the contrast agent used was Gadobutrol. Our patient presented approximately 40 minutes after the procedure with acute encephalopathy, a clinical presentation consistent with prior gadolinium-related pSAH cases. Imaging findings also mirrored prior reports, with the initial noncontrast CT of the head revealing hyperdensities in the interhemispheric falx and bilateral cortical sulci, mimicking a true SAH. CT angiography excluded aneurysmal rupture, and MRI later confirmed the presence of sulcal T1 and T2 hyperintensities without associated edema or infarction—features consistent with gadolinium neurotoxicity rather than hemorrhage. Notably, symptom onset in this case fits within the previously reported window of immediate to 1 day post-procedure, and like most prior cases, the patient experienced complete clinical recovery within a few days.

Table 1. Reported cases of pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to intrathecal or epidural contrast exposure

Table 1 summarizes reported cases of pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage following intrathecal or epidural contrast exposure. Most involved gadolinium-based agents during lumbar procedures, with symptom onset ranging from immediate to 1 day. Presenting symptoms and imaging often mimicked true SAH, though the majority of cases resolved with supportive care.

Abbreviations: AMS, altered mental status; CC, cubic centimeters; CT, computed tomography; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; LESI, lumbar epidural steroid injection; LP, lumbar puncture; LPEN, lumbar percutaneous epidural neuroplasty; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; NR, not reported; N/V, nausea/vomiting.

While prior reports of gadolinium-induced pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage (pSAH) have been limited to lumbar myelograms, lumbar epidural steroid injections, and neuroplasty procedures, this case highlights that even extradural cervical interventions without intravascular uptake carry a risk of inadvertent contrast exposure to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how contrast may reach the CSF, including age-related increases in blood–brain barrier permeability and congestion of the meningeal lymphatics, which may facilitate leakage from perivascular spaces into the subarachnoid space.14 Ultimately, further research is needed to better characterize the anatomic pathways, patient-specific risk factors, and procedural variables that contribute to this rare but clinically significant phenomenon.

In the setting of the emergency department, this case underscores the importance of obtaining a thorough procedural history when evaluating patients with acute neurologic changes and imaging concerning for subarachnoid hemorrhage. A noncontrast head CT showing subarachnoid hyperdensities often prompts an aggressive diagnostic cascade—including blood pressure management, CTA, lumbar puncture, and ICU admission.15 However, in patients with recent neuraxial interventions, particularly those involving gadolinium-based contrast agents, pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage should be considered early in the differential. Asking targeted questions about recent neuraxial procedures, contrast allergies, and timing of symptom onset can shift the clinical approach and prevent unnecessary invasive testing.

Once pSAH is suspected, emergency physicians should tailor management based on the patient’s clinical condition rather than radiographic appearance alone. Most reported cases, including ours, have resolved with supportive care and close neurologic monitoring. Interventions typically used for aneurysmal SAH—such as nimodipine administration or lumbar puncture—may be unnecessary and potentially harmful. In stable patients with reassuring neurologic exams and clear procedural context, conservative observation and follow-up imaging may be more appropriate than an invasive workup. Early recognition of similar presentations and history allows emergency physicians to avoid diagnostic pitfalls and prevent costly, invasive procedures.

Conclusion

This case highlights pSAH as a rare but important complication of spinal procedures utilizing GBCAs, even in cervical medial branch blocks where intrathecal access is not intended. Awareness of this phenomenon is critical, as its clinical and radiographic presentation can closely mimic aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, leading to potential diagnostic confusion. A thorough understanding of patient history, procedural details, and careful interpretation of imaging can help distinguish pSAH from true hemorrhage and avoid unnecessary invasive testing. As the use of alternative contrast agents becomes more common in patients with iodinated contrast allergies, clinicians should remain vigilant for this rare complication and consider it in the differential diagnosis of acute encephalopathy following spinal interventions.

References

- Connolly ES Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association.Stroke. 2012 June;43(6):1711-1737.

- Lawton MT, Vates GE. Subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2017, July 20;377(3):257-266.

- Samardzic D, Thamburaj K. Magnetic resonance characteristics and susceptibility weighted imaging of the brain in gadolinium encephalopathy. J Neuroimaging. 2015 Jan/Feb;25(1):136–139.

- Lin CY, Lai PH, Fu JH, Wang PC, Pan HB. Pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage: a potential imaging pitfall. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2014 Aug;65(3):225-231.

- Arlt S, Cepek L, Rustenbeck HH, Prange H, Reimers CD. Gadolinium encephalopathy due to accidental intrathecal administration of gadopentetate dimeglumine. J Neurol. 2007 June;254(6):810-812.

- Hasan TF, Duarte W, Akinduro OO, Goldstein ED, Hurst R, Haranhalli N, Miller DA, Wharen RE, Tawk RG, & Freeman WD. Nonaneurysmal “pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage” computed tomography patterns: Challenges in an acute decision-making heuristics. J Stroke Cerebrovascular Dis. (2018). 27(9), 2319-2326

- Oh CH, An SD, Choi SH et al. Contrast mimicking a subarachnoid hemorrhage after lumbar percutaneous epidural neuroplasty: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2013;7, 88.

- Samardzic D, Thamburaj K. Magnetic resonance characteristics and susceptibility weighted imaging of the brain in gadolinium encephalopathy. J Neuroimaging. 2015 Jan/Feb;25(1):136–139.

- Platt A, El Ammar F, Collins J, Ramos E, Goldenberg FD. Pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage and gadolinium encephalopathy following lumbar epidural steroid injection. Radiol Case Rep. 2020 Aug 19;15(1):1935‑1938.

- Sasaki, Yuya, Keisuke Ishii, and Issei Ishii. Myelography-associated pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage. Vis J Emerg Med. 2016 Oct;5:25-26.

- Kim DW, Choi S, Lee SM. Contrast media mimicking subarachnoid hemorrhage after intrathecal injection in a patient with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Acute Crit Care. 2022 Nov;37(3):474-476.

- Horlocker TT, Wedel DJ, Rowlingson JC, Enneking FK, Kopp SL, Benzon HT, et al. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: Fourth edition evidence-based guidelines. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine. 2018 Apr;43(3):263–309.

- Eckel TS, Breiter SN, Monsein LH. Subarachnoid contrast enhancement after spinal angiography mimicking diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998 Feb;170(2):503-5.

- Naganawa S, Ito R, Kawai H, Taoka T, Yoshida T, Sone M. Confirmation of age-dependence in the leakage of contrast medium around the cortical veins into cerebrospinal fluid after intravenous administration of gadolinium-based contrast agent. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2020 Dec 1;19(1):64–70.

- Petridis AK, Kamp MA, Cornelius JF, et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017 Mar 31;114(13):226-236.