Differentiating benign peripheral conditions from central nervous system lesions like strokes can be difficult. Enter the HINTS exam - the objective measure.

If one were to survey a group of EM physicians on a chief complaint that irks them the most, "dizziness" would probably top that list.

Although dizziness only comprises 3.5% of all ED visits per year1 it produces anxiety because of its broad, dangerous differential. Residents are taught to dichotomize dizziness by subjectively asking patients to categorize it into "lightheadedness" or "vertiginous" categories. This question often confuses the patient and can end in a misleading diagnosis. For example, almost half the patients diagnosed with cardiac etiologies initially endorsed vertiginous symptoms.1 Rather than ask "What do you mean by dizzy?", we should seek to delineate dizziness like any other chief complaint - focusing on timing, triggers, associated symptoms, and relevant medical history. We also need an objective exam to delineate peripheral vs. central vertigo.

Differentiating benign peripheral conditions from central nervous system lesions like strokes can be difficult, as the focal neurological deficits that can accompany central causes are essentially inconspicuous.

Enter the HINTS exam - the objective measure.

What is HINTS?

In 2009, Kattah et al. examined the diagnostic accuracy of combining 3 previously established bedside diagnostic tests:

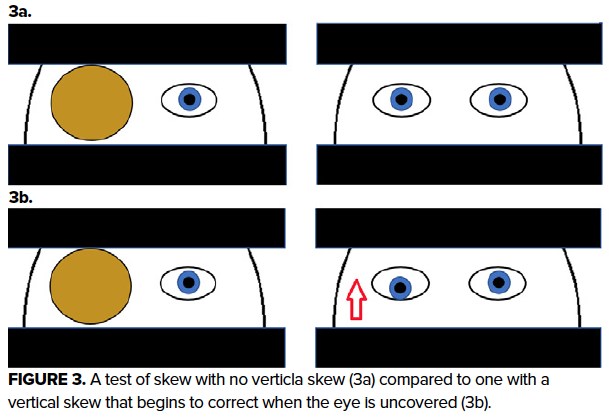

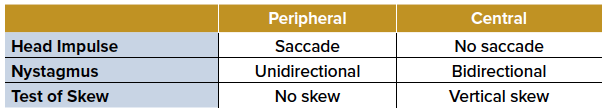

- Horizontal head impulse testing (Head Impulse)

- Direction-changing nystagmus in eccentric gaze (Nystagmus)

- Vertical skew (Test of Skew)

These tests were combined and have since been used as a tool to identify posterior circulation stroke: the Head Impulse, Nystagmus, Test of Skew (HINTS).2 A single central finding on any of the 3 components "rules-in" a posterior circulation stroke, and further testing/treatment is indicated.

The Kattah study demonstrated the HINTS exam was more sensitive than an MRI in the first 24 hours. Interestingly, patients with a positive HINTS exam and an initial negative MRI were later found to have positive MRI findings for a stroke. Studies have shown sensitivity of the HINTS to be 96-100%, with specificity 96-98%.3

The most challenging aspect of the HINTS exam is identifying the appropriate patient. First, the patient must present with acute vestibular syndrome (AVS): vertigo, nystagmus, nausea/vomiting, head-motion intolerance, unsteady gait. Second, the patient must currently be symptomatic with nystagmus either at rest or with lateral gaze. If the patient is not currently symptomatic, it can result in false negatives. For example, the absence of corrective saccade on the head impulse test is indicative of a central cause of vertigo, but the saccade will also likely be absent in any patient not currently symptomatic.

Performing the Exam

Horizontal head impulse testing (Head Impulse)

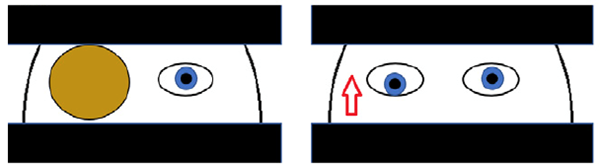

- Hold the patient's head, allowing their mandible to rest and relax into your palms. Ask the patient to fixate on an object (ie, your nose). Then, quickly and gently move the patient's head to the left or right and then back to the neutral position again.

- Central Finding: Absence of saccade (no large beats of nystagmus as the eyes "catch up" to re-fixate on examiner's nose) is concerning.

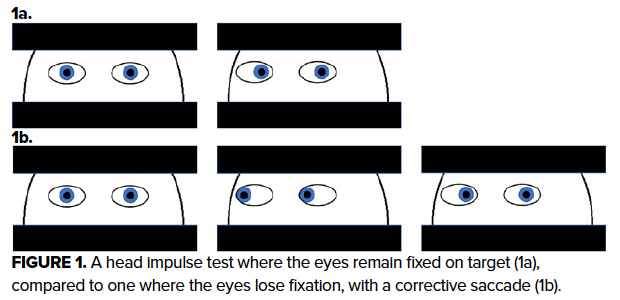

Direction-changing nystagmus in eccentric gaze (Nystagmus)

- Assess for a presence of nystagmus.

- Central Finding: Any vertical nystagmus or horizontal nystagmus that changes direction with lateral gaze ("bidirectional nystagmus") is concerning.

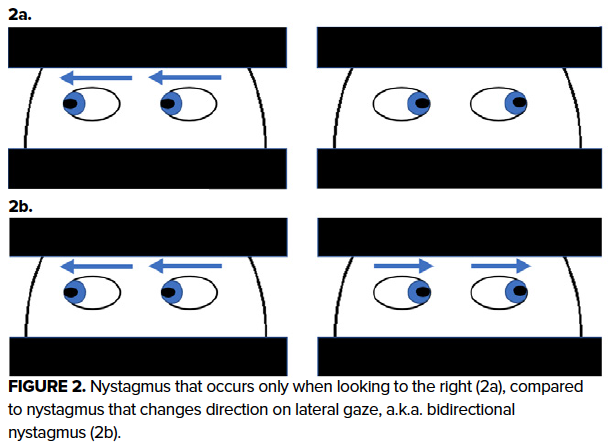

Vertical skew (Test of Skew)

- Cover one eye for several seconds and then uncover that eye quickly.

- Central Finding: Realigning of the eye vertically is concerning.

- Caveat: This response may fatigue over serial exams during a short time period.

HINTS in the ED

The 2009 HINTS exam study was part of a 9-year data collection period on stroke in AVS at a regional stroke referral center for 25 community hospitals. It included a high-risk cohort, with inclusion criteria of AVS and at least one stroke risk factor, with most patients having > 2 risk factors. While the overall rate of stroke as a cause of AVS is approximately 6%, it was > 50% in these studies.

Although the HINTS exam was originally developed and performed by neuro-ophthalmologists, its use by ED physicians has been on the rise.4,5 When performed and interpreted correctly, the HINTS exam is a useful bedside tool for identification of a posterior stroke in patients with AVS. Thus, when examining patients with dizziness, it becomes paramount to perform an objective study such as HINTS to delineate central vs. peripheral.

References

1. Tehrani AS, Kattah JC, Kerber KA, Gold DR, Zee DS, Urrutia VC, Newman-Toker DE. Diagnosing stroke in acute dizziness and vertigo: pitfalls and pearls. Stroke. 2018;49(3):788-795.

2. Edlow JA, Gurley KL, Newman-Toker DE. A new diagnostic approach to the adult patient with acute dizziness. J Emerg Med. 2018;54(4):469–483.

3. Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009;40:3504–3510.

4. Newman-Toker DE, Kerber KA, Hsieh YH, Pula JH, Omron R, et al. HINTS outperforms ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(10):987–996.

5. Vanni S, Nazerian P, Casati C, et al. Can emergency physicians accurately and reliably assess acute vertigo in the emergency department? Emerg Med Australas. 2015;27:126–31.

6. Henriksen AC, Hallas P. Inter-rater variability in the interpretation of the head impulse test results. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2018;5(1): 69–70.