Debriefing and Decompressing

Chapter 2 Audio

GROUP DEBRIEFS

What is a debrief? A debrief is a dialogue to discuss the actions and decisions involved in a patient care situation and how to improve for the future.1

Why debrief?

- To learn both how to function within a team setting and about your individual successes and mistakes

- To regroup and take time to reflect on the incident that just occurred

- To better understand the case and why it was led a certain way

- To recognize different roles and that blame does not fall on any one individual

- For patient safety and quality improvement - that is, to be cognizant of how your actions affect the patient and continue to improve with each future patient2-5

Who debriefs? Everyone involved in the case: Attendings, residents, medical students, nurses, technicians, social workers, respiratory therapists, etc. The debrief leader may be anyone in the group who chooses to arrange the meeting. The debrief leader does not have to be the clinical code leader.

When do we debrief?

- After acute resuscitations

- After significant, unusual, or poor-outcome cases

- Regularly for teaching points

Where do we debrief? In a quiet, preferably private, space. Options include the staff lounge, computer work area, grief room.

How long do we debrief? 7-10 minutes. This is intended to fit within the ED workflow.

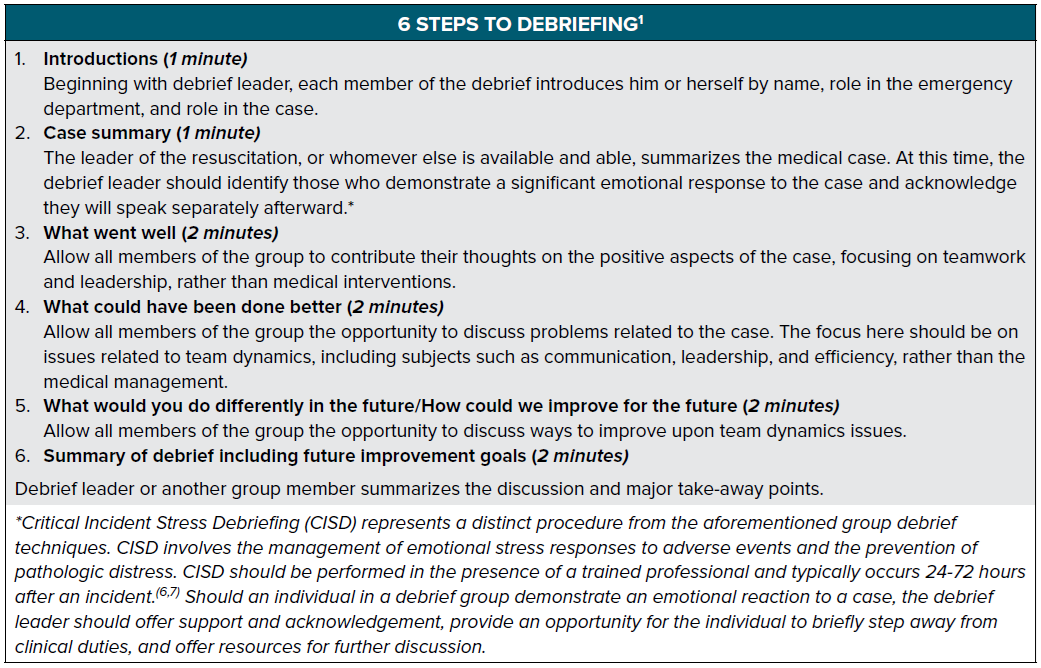

How do we debrief? In 6 easy steps outlined below.

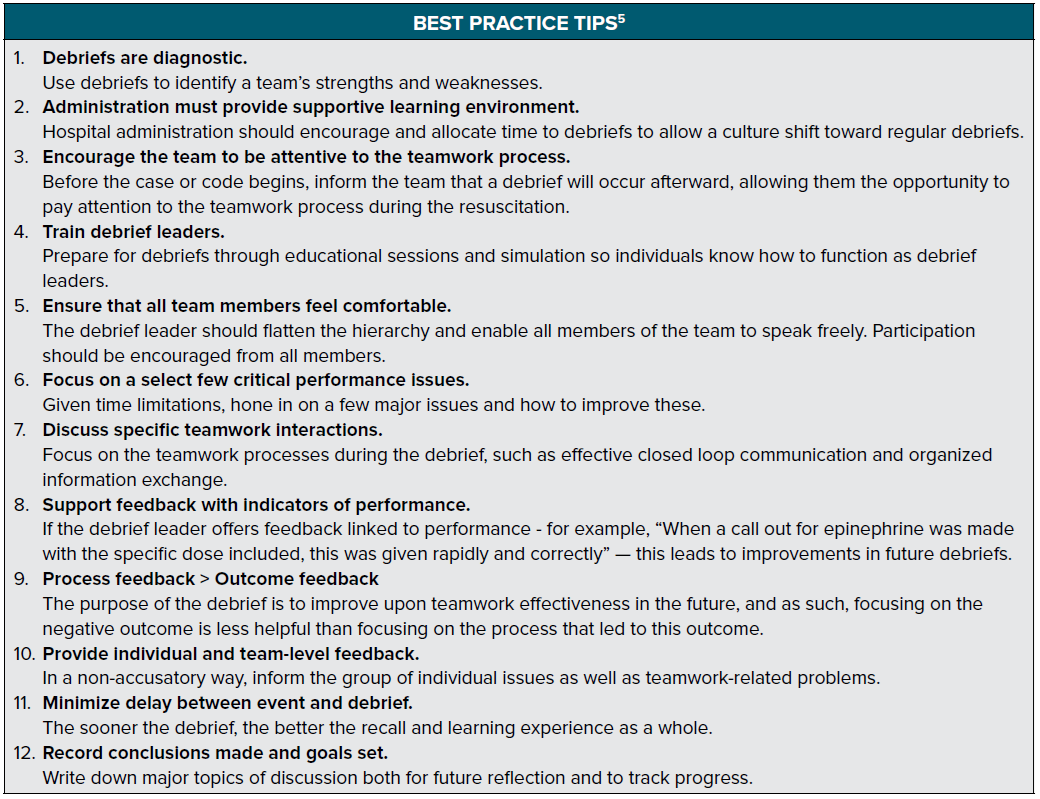

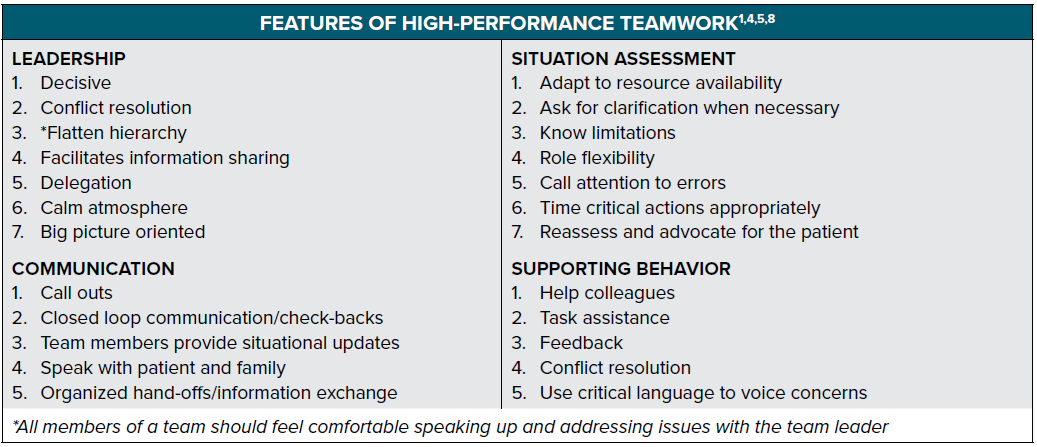

How do we ensure efficient, high-quality debriefs wherein we are evaluating the proper features of teamwork? Features of high-performance teamwork are outlined in the following table. These represent important features of an effective team and should be evaluated during the debrief.

What are some tips to ensure a smooth debrief? Debriefs are not always easy, and roadblocks may be encountered. Read

on for tips on how to achieve successful debriefs and avoid common pitfalls.

INDIVIDUAL DEBRIEFS

Debriefing and decompressing can take on many different shapes and sizes. The purpose is for individuals to express themselves in a healthy and cathartic manner.

The Arts: Reflective Writing, Painting/Drawing

Reflective Writing

Reflective writing allows an individual to place thoughts onto paper, whether in the form of a story, creative piece, or literal recounting of an event and associated emotions. Writing about a difficult event can help one to sort through emotions and even discover those about which he or she was unaware. This process can help one to draw conclusions and gain a sense of closure.

Reflective writing may be done privately as journaling, or encouraged as part of a curriculum. At Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, a writing curriculum was established to continue throughout all years of medical school, with new topics and types of writing introduced.9 Students would graduate with a final portfolio of their experiences as they personally interpreted them.

Painting/Drawing

Creating artwork through painting and drawing may provide an important outlet for the emotional responses one may have to a workplace experience. This form of decompressing enables a release of sadness, fear, anxiety, and guilt into a concrete creation that can be used privately or shared to encourage discussion about a difficult event. In the words of one artist-physician, “Once formed into a piece of art, these life-altering moments … allow all of us to join in reflection in our time and at our own pace.”10

Exercise

Physical exercise is a well-studied medium for stress relief and decompression. Exercise can allow for clearing of the mind through meditation in motion, as one is forced to focus on a single task. Regarding mood, not only do endorphins promote positive states of mind, but also exercise in general improves self-confidence and reduces feelings of depression and anxiety.11 Exercise can be adjusted to fit into a busy schedule. Examples include:

- Walking: may be done in long stretches or short increments of 10 minutes throughout the day

- Running: intervals or long distance

- Swimming

- Yoga

- Group exercise: enables a sense of camaraderie and shared experience

- Sports: the gratification of teamwork and socializing accompanies the fitness benefits

Simply taking the stairs rather than an elevator and opting to walk rather than drive can have significant cumulative effects as well. Finding the right exercise for a certain lifestyle is important and the benefits can be great.

Social Support Systems

While debriefing in the hospital may provide one type of decompression, sometimes further closure is required through discussion with those in our social support systems. Protecting patient information is important in these cases; however, expressing one’s emotional reactions is safe and often necessary. One may speak with different individuals for different purposes. For example, venting about work-related issues may be easiest among family and colleagues, whereas personal issues may be best shared with friends. Determining whom one trusts and whose advice one appreciates early in a career may be immensely helpful as new concerning scenarios are encountered.

Individual Therapy

For many individuals, sharing experiences and emotional reactions with colleagues and loved ones may not come easily. Therapy with a trained psychologist or psychiatrist who remains impartial and uninvolved in one’s personal life is a safe option. This allows for discussion with an objective, confidential audience. Some hospital systems have employee assistance programs which can provide a therapist, others may require a personal search. For specific interventions and approaches, see the Sample Meditation Exercises section in the chapter “Mindfulness and the Emergency Medicine Mind” of this guide.

REFERENCES

- Kessler DO, Cheng A, Mullan PC. Debriefing in the emergency department after clinical events: a practical guide. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(6):690-698.

- Couper K, Perkins GD. Debriefing after resuscitation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013;19(3):188-194.

- Nadir N, Bentley S, Papanagnou D, et al. Characteristics of Real-Time, Non-Critical Incident Debriefing Practices in the Emergency Department. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(1):146-151.

- Rudolph JW, Simon R, Raemer DR, et al. Debriefing as formative assessment: closing performance gaps in medical education. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(11):1010-1016.

- Salas E, Klein C, King H, et al. Debriefing medical teams: 12 evidence-based best practices and tips. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(9):518-527.

- Everly GS, Flannery RB, Mitchell JT. Critical incident stress management (CISM): A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2000;5(1):23-40.

- Wuthnow J, Elwell S, Quillen JN, et al. Implementing an ED Critical Incident Stress Management Team. J Emerg Nurs. 2016;42(6):474-480.

- Carne B, Kennedy M, Gray T. Review article: Crisis resource management in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24(1):7-13.

- Isaacson JH, Salas R, Koch C, et al. Reflective writing in the competency-based curriculum at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine. Perm J. 2008;12(2):82.

- McAdams RM. Coping on Canvas. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(9):795-795.

- Anderson E, Shivakumar G. Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Anxiety. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:27.