Rapid Team-Building

Chapter 3 Audio

Most individuals employed in full-time jobs spend a substantial number of their waking hours dedicated to work or work-related activities. In the field of medicine, residency is at the far end of the spectrum, with residents not only being obligated to spend significantly more of their time physically at work, but also a significant amount of their personal time focused on supplementing their on-shift education with reading and building an academic portfolio. Consequently, residents often spend more time with work colleagues than with their own families and friends.

Within the ED, emergency medicine residents face the additional challenge of working in one of the most highly charged environments within the hospital. It is within this environment that physicians are tasked to not only make complicated medical decisions and navigate the complexities of the hospital care delivery system, but also contend with the emotional experience of their patients as well as their own and that of their team.

The concept of the physician as a team captain is easily visible in the ED, where the attending physician is often the center of the beehive, surrounded by students and residents waiting to present patients, nurses awaiting signatures on electrocardiograms, family members waiting to speak to the doctor in charge, or consultants simply looking for the easiest target to share information. Unfortunately, the skills needed to lead the team remain largely a part of an informal and hidden curriculum in residency – ie, learned by direct observation but rarely explicitly taught.1 In this capacity, the physician must be not only the healer and teacher, but also role model, team builder, manager of complex relationships with other physicians, trainees, consultants, physician assistants, nurses, techs, transporters, as well as administrator to ensure that multiple concurrent care plans are efficiently carried out, and quite importantly, morale monitor ensure that everyone feels appreciated for their hard work.

This chapter discusses simple strategies to assist in the development of a healthy and resilient team dynamic within the ED, as well as create positive relationships with your colleagues, forming the foundation to ensure a successful shift and career in the ED.

DEPARTMENTAL TEAM-BUILDING

Learn Names

Learning someone’s name is crucial and is especially important in teaching institutions where there is a high turnover of staff. Knowing someone’s name in the hospital changes the dynamics of the relationship by infusing a layer of familiarity, as well as accountability. Conversely, remind yourself of the horrible feeling you may have had when you’ve been working with someone for a period of time, but you don’t know their name.

Team Briefs & Huddles

At the start of shift change call for a team brief – and be sure to include RNs, techs and support staff. Have everyone introduce themselves and their role. It will help you remember names more easily, which will make for a more pleasant working environment. You can call another team huddle midway through a shift when you see the department is getting busier and more tense as a means to take people to a positive place by providing a cognitive break, a few pats on the back, and some chocolate.

In need of some rapid team bonding during the huddle? Try one of these quick icebreakers.

- Ask your team members to share:

- Name, role, and “One Good Thing” going on in their lives (upcoming vacation, recent promotion, how their child is doing in school, etc.)

- The name of their pets

- Their favorite band

- Their childhood nickname

- Their first email address or screen name

- The farthest they have ever travelled

- Why they chose emergency medicine as a career

- Ask a hypothetical question

- “What would you do with a million dollars?”

- “If you had a boat, what would you name it?”

- “If you could choose another career outside of medicine, what would you do?”

- Learn a phrase in a new language! Do any members of your team speak another language? Ask them to teach the team a simple phrase, such as “Hello, my name is ___” or “Where is your pain?”

- Once your team gets used to your daily event, you can eventually make the game more active by trying “Snap Pass” or using other improvisational icebreaker games.

- Snap Pass

- To play “Snap Pass,” the team leader will first start snapping her/his fingers, and concurrently, state their name and role. The team leader will then look another team member in the eyes and “Pass-the-Snap” to that person, who must “Catch-the-Snap” and then state their name and role before passing it on to the next team member.

- This type of improv game can be slightly altered by turning the “snap” into a clap, or any other imaginary object like volleyball, tennis ball, hockey puck that can be passed around.2

- Snap Pass

Three-Ring Binder

Create 3-ring binders with everyone’s picture and name, including all doctors, nurses, housekeeping, and administrators. Leave a copy in the common break areas for everyone to leaf through during a break.

Facebook and Other Social Media

Another option to assist in team-building at work is to become friends on Facebook (or other platforms) and learn a little about your colleagues. If you choose this option, you will have to accept that your actions on your profile are equally as reflective of you as your real-life actions; consequently, you will have to manage your profile responsibly. Please note, before befriending and workmates, you may need to adjust several privacy settings and/or remove photos and ensure your profile is “clean.”

Managing social media has become increasingly complicated, with issues ranging from deciding what to post, with whom to become friends, and what to “like.” One thing to be certain of though, is that anything you post online may become discoverable at some point, thus we must be extremely cautious with our online presence and the content we post.

Respecting Everyone (and we mean EVERYONE)

10 & 5 Rule3

The 10 & 5 rule is typically employed in the hospitality and service industry and recommends that if you are within 5 feet of someone say hello, or if you are within 10 feet of someone, make eye contact.

Thank Your Team

It is as simple as taking a moment to give them praise and thank them on-shift when you witness them doing a great job or being kind to a patient or other provider. Read your colleagues, and if you see them struggling, offer a pat on the back – it can go a long way. Depending on the individual or situation, you may want to provide the praise in public or privately. Conversely, if needed, be sure to criticize in private. As a departmental project, you may want to consider creating a “Heroes” or “All-Stars” box where individuals can submit the names of colleagues with a brief description of how they went above-and-beyond for a patient, colleague, etc. The names and events can be posted monthly, providing departmental recognition. If the situation merits it, take that extra step and contact their supervisor to ensure their positive actions are recognized within their department.

Stress in the ED is natural, and on occasion, tempers can flare with harsh words being uttered either intentionally or unintentionally. After the situation has been resolved, it is vitally important to take a moment to perform a personal root-cause-analysis, then discuss it with and apologize to the other party. Though this is a difficult step, ultimately it will lead to a better understanding of the other individual and how to cope with them in the future.

Effective Verbal Communication and Involving All Team Members in Plans

All health care providers working in the emergency department are there for sole purpose of taking care of patients. Thus effectively communicating the details of a patient’s treatment plan is central to its implementation. Often, however, junior physicians can get into a “silo” mentality and work exclusively with the electronic medical record and neglect the nurse on the receiving end of the orders. Make it a priority to verbally communicate treatment plans, important case details, and priority cases with your nursing and ancillary staff. Not only does it build team cohesiveness, but also may lead to teachable moments for each.4

Be Nice to the Nurses

It is always a good idea to be seen as a contributor within the department and not above any task, whether it is transporting a patient to x-ray, emptying a urinal, making a bed, or collecting blood. All tasks are important tasks and all are a part of patient care. Though these are technically not a physician’s job, depending on your hospital, the time of day, whether there is a full moon, your department can be easily overwhelmed, and helping out in these high-volume times can go a very long way to show that not only are your nurses a part of your team, but you are a part of theirs.

Socializing in the Emergency Department

Share some laugh as well as the tears.

While on-shift, preferably if it slows down, don’t forget to take a few minutes to relax the team and have a laugh. Typically this may revolve around coffee and snacks, so consider intermittently surprising your team with a few treats.

Conversely, the ED also exposes us to extremely traumatizing events. Don’t be afraid to pause to care for your colleague who appears to have been shaken by an event or situation.

Socializing Outside the Emergency Department

Most departments have traditions to host annual holiday celebrations, which can be a great way to “blow off some steam” together. While these are great ways to consolidate friendships and have fun, never forget they are work functions. As a work function, it is important to maintain control and not consume too much alcohol while at the same time having fun. Using this time to get to know your attendings and foster better mentorship relationships within your internal network can help create great opportunities down the road.5

INTERDEPARTMENTAL TEAM-BUILDING

Consultations

Relationships between emergency physicians and consultants, especially in training institutions, are inherently complicated. The interaction begins with the emergency physician, who has evaluated the patient and determined that either the skills needed to manage the patient are outside the scope of their training, or the patient will require inpatient admission to a specific service. On the other hand, the consultant is being drawn into a new situation and introduced to an emergency patient with an active disease process. As well, from the practical standpoint, the consultation adds another task to the consultant’s daily task list, interrupts current tasks, meals – or even wakes them from sleep. The consultant, often an intern, will have to evaluate the patient and in turn convince their senior and attending that the patient does indeed require their services. Emergency physicians must respect, empathize, and be prepared to effectively and deliberately communicate the question of clinical importance.6,7

Consultation discussions themselves can be extremely stressful for attendings and trainees alike for a variety of reasons, including complex patient factors, hospital system issues, environmental factors, and even personal consultant issues. Historically, the skills needed to conduct a consultation have been picked up on-the-job by watching a supervisor or senior resident; however, there is a benefit to discussing and teaching these skills. Consider formal teaching sessions in small groups at conference to discuss and practice strategies on how to consult.8 A commonly used standard of communication today is “SBAR” (situation, background, assessment, recommendation). Using this tool of communication can help organize thoughts for the emergency physician delivering the consultation and prepare the consultant for receiving the information. SBAR leads to clear, concise information – reducing frustration on the part of the consultant. Being mindful of the plight of the consultant is important, too. Remember they are all busy while also fielding pages and calls, so if communication is not clear in the first 1-2 minutes of a call it can taint the remainder of the interaction.

Engage Professionally with Your Colleagues\

Consider hosting an invited lecture series, where a senior EM resident lectures to another department on a related EM subject, and vice-versa. It’s a great opportunity for two groups to spend time in the same room and interact in environments that are less charged. Add to the event with coffee and light snacks, at least. As an added benefit, joint lectures can boost the CV of the organizer and presenters as well.

Interdepartmental Socializing Outside the Emergency Department

Most residencies provide protected time for weekly conference. Take advantage of this by arranging an activity the night before conference or the afternoon afterward, and invite another department. Consider starting an annual tradition early in the academic year to start the year off on the right foot.

Bad Interactions

On occasion, interactions can be quite poor or even descend into the realm of disrespect. Beyond infusing negativity into your day, disrespect and unprofessional behavior can impact patient care. For the recipient, especially the more junior residents, in the immediate post-insult period on-shift, there is a complex mix of intense feelings that may impact decision-making and inhibit normal function.9 Though many people nimbly suggest “leave work at the door,” it isn’t always easy, and these negative feelings can be brought home and impact personal lives. The longer term sequelae of dealing with unprofessional behavior in combination with other factors can contribute to burnout and depression. Patient care can suffer as well. Consider, for instance, a surgical resident who has reputation as being rude, non-collegial, and unapproachable. Some emergency physicians will delay consulting until labs or imaging are finished, and this delay may have a detrimental impact on OR scheduling, bed allocation, initiation of transfer, or other elements of medical management.

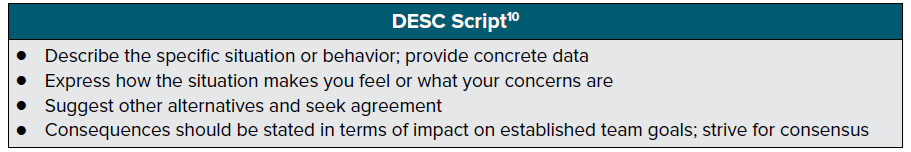

One tool that can be used to resolve conflicts is the DESC Script10 from TeamSTEPPS®.

Immediately following a bad exchange, the emotional charge may be too high to have a dispassionate conversation. Take some time to collect yourself and your thoughts. One example is, “ When you called me useless in front of the patient and their family it made me feel like you don’t respect me and negatively affected my rapport with the patient. If you have feedback for me in the future, can we please talk away from the bedside? I’m afraid if this continues then we won’t be able to work together in a productive manner.”

If after your best efforts the unprofessional behavior continues, discuss the incident with your chief or program directors, as this may not be a one-time issue with that resident, consultant, or staff member. Given the nature of our shift-work schedules, identifying problematic individuals is very difficult; we tend to dismiss rude behavior as a one-time incident. This may not be the case, which is why it is quite important to discuss with your supervisors, who may already be tracking this individual. Poor attitudes and behaviors are not new in medicine, and your program likely has a reporting system and remediation plans already in place.11

Harassment of any form should not exist in the workplace. If you do experience it, there are many avenues by which you should seek counsel, including your program directors, department leadership, GME office, ombuds office, etc. These types of interpersonal conflicts should never be dealt with on a one-on-one basis. By seeking institutional-level assistance, you may help identify problematic behavior patterns that otherwise could go unnoticed.

In conclusion, residency life is both rewarding and challenging. In our local hospital communities, we can help reduce the challenges by working together better as teams. Fundamental to this is being respectful and treating each other exactly how we’d like to be treated. Being mindful of each situation and individual we interact with will help reduce most conflicts and help promote a healthier environments for both providers and patients.

REFERE

- Hafferty FW. Beyond Curriculum Reform: Confronting Medicine’s Hidden Curriculum. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;37(4):403-7.

- Merlin S. Improv Comedy Icebreaker Games: Improv Comedy Games: Pass the Clap. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eUP1a-9q2aA. Accessed August 26, 2017.

- Gurtman J. What is the 10 and 5 Staff Rule? https://www.coylehospitality.com/hotels-resorts-inns/what-is-the-10-and-5-staff-rule/. Published September 2013. Accessed August 26, 2017

- Abourbih D, Armstrong S, Nixon K, Ackery AD. Communication between nurses and physicians: strategies to surviving in the emergency department trenches. Emerg Med Australas. 2015;27(1):80-2.

- Gottlieb M, Sheehy M, Chan T. Number Needed to Meet: Ten Strategies for Improving Resident Networking Opportunities. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(6):740-743.

- Kessler CS, Tadisina KK, Saks M, Franzen D, Woods R, Banh KV, et al. The 5Cs of Consultation: Training Medical Students to Communicate Effectively in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2016;49(5):713-21.

- Ackery AD, Adams JW, Brooks SC, Detsky AS. How to give a consultation and how to get a consultation. CJEM. 2011;13(3):169-71.

- Kessler CS, Chan T, Loeb JM, Malka ST. I'm clear, you're clear, we're all clear: improving consultation communication skills in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):753-8.

- Leape LL, Shore MF, Dienstag JL, Mayer RJ, Edgman-Levitan S, Meyer GS, Healy GB. Perspective: a culture of respect, part 1: the nature and causes of disrespectful behavior by physicians. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):845-52

- TeamSTEPPS® Essentials Instructional Module and Course Slides. Content last reviewed March 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/index.html.

- Leape LL, Shore MF, Dienstag JL, Mayer RJ, Edgman-Levitan S, Meyer GS, Healy GB. Perspective: a culture of respect, part 2: creating a culture of respect. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):853-8.