Sleep Better

Chapter 4 Audio

SLEEP BASICS

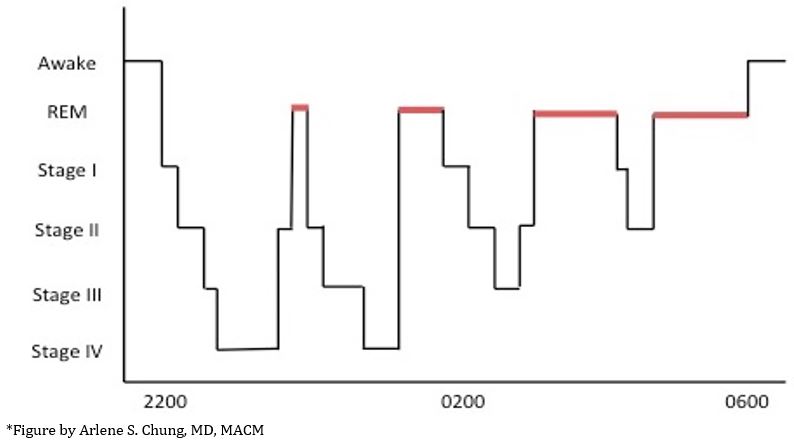

Normal sleep has 5 stages.

- Stage I is the first and lightest phase of sleep. If someone taps you on the shoulder during Stage I, you might not even realize you had been sleeping.

- Stage II is a little deeper than Stage I, but still fairly shallow and not all that restful.

- Stages III and IV are considered the “deep sleep” phases when real recovery from a long day’s work happens.

- REM (rapid eye-movement) sleep is super-special. In this phase, it’s almost impossible to tell whether you’re awake or asleep in REM on an EEG. One major difference, of course, is that your whole body except for your eyes is paralyzed in REM sleep so you don’t go around acting out your dreams, since the most vivid dreams happen in this stage of sleep.

Over the course of a typical 8-hour night, you’ll cycle several times through all 5 stages, with each stage lasting about 90 minutes and proportionally more REM sleep as the night goes on toward morning.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM BASICS

The word “circadian” comes from the Latin circa, meaning “around,” and dia, meaning “day.” It describes any biological rhythm that follows an approximately 24-hour cycle. This includes things like body temperature, blood pressure, cortisol secretion, and bowel movements. External cues (called zeitgeibers, meaning “time givers” in German) such as sunlight and mealtimes help to keep your body’s circadian rhythm in line with the external world, so you’re sleepy when it’s dark outside and awake when the sun’s up.

SHIFT SCHEDULING AND SMART SLEEPING

Misalignment of sleep timing and circadian rhythm is the primary reason shift work is so taxing on the body. This is why sleeping during the day doesn’t typically feel as restful as sleeping at night. However, it is possible to make the day-to-night (and night-to-day) transitions easier by understanding how your body responds and scheduling your shifts, requests off, and personal life accordingly.

- It’s easier to transition from days → evenings → nights.

- Your body’s natural circadian rhythm is actually closer to 25 hours. This means it’s easier to stay up later and get up later than vice versa. This also explains why jet lag feels worse when traveling east compared to west.

- What you can do:

- If you know you have a long string of night shifts coming up, prepare by going to bed progressively later for the few days leading up to your first night shift.

- Encourage the person responsible for scheduling to use circadian rhythm principles when scheduling shifts. This is the official recommendation by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP).1,2 An example of a circadian rhythm principle would be to avoid rapid night-to-day transitions.

- It’s easier to transition fully (or not at all).

- It takes your circadian body rhythms several days to transition fully from days to nights (or nights to days). A string of 4-5 night shifts may actually be the most difficult on your body because you only have time to partially transition to nights before having to switch back to days.

- What you can do:

- If you have a day or two off between multiple night shifts, try to stay on a nighttime schedule as much as possible. This might mean sleeping in, staying up late, or taking a long nap during the daytime if you can’t sleep in.

- If you have only one or two night shifts in a row, it may be easier to stay on a daytime schedule as much as possible. For example, after a single night shift try to be awake for a reasonable period of time during the day after the shift and go to bed at a normal hour.

- Encourage the person responsible for scheduling to use circadian rhythm principles when scheduling shifts, as recommended by ACEP.1,2 An example of a circadian rhythm principle would be to schedule a “night month” once or twice a year while the remainder of the year consists of primarily day shifts. Another alternative would be to spit a single ED block into two weeks of days and two weeks of nights.

- Use your zeitgebers wisely

- Sunlight is one of the most powerful zeitgebers around.

- Expose your eyes to sunlight in the “morning” or at the beginning of the time period when you want to be awake. You can substitute bright lights or a light a box if no sunlight is available (see “Non-pharmacologic Aids”).

- Limit your exposure to sunlight at “evening” or during the time period leading up to when you’d like to sleep. Wearing sunglasses when leaving work after a night shift and other light filtering tools may help (see “Non-pharmacologic Aids”).

- Other external cues that can help set your circadian rhythm properly (either to day or night) include:

- Exercise

- Exercise at the beginning of the time period when you want to be awake can mimic the blood pressure, temperature, and cortisol rise that usually occurs during the daytime. However, note that exercising too close to bedtime can actually prolong wakefulness.

- Meal times

- Use your enteric nervous system to entrain your central nervous system. Schedule mealtimes that correspond to breakfast, lunch, and dinner of your “daytime,” whether you want that to be during the day or at night.

- Supplements (ie, melatonin; see “Pharmacologic Aids - Sedatives”)

- Exercise

- Sunlight is one of the most powerful zeitgebers around.

PHARMACOLOGIC AIDS

Stimulants

- Caffeine

- Caffeine is a stimulant belonging to the class of methylxanthines. It is the most widely used psychoactive substance in the world. Essentially it blocks adenosine in the sleepy receptors in your brain. When ingested from beverages such as coffee and soda, caffeine is readily absorbed by the small intestine within 45 minutes.3 The half-life is relatively long and varies from 3-7 hours depending on factors such as pregnancy and age.

- Small doses of caffeine (0.3mg/kg or 20mg for a 70kg person) administered once an hour have shown promise in maintaining cognitive function during extended periods of wakefulness.4

- At doses of 600mg, the stimulant effects of caffeine may approximate those of modafinil or armodafinil (see below), although comparable effects have been seen with doses of caffeine as low as 200mg.5

- Nicotine decreases the half-life of caffeine, making it less effective per dose.

- Side effects can be similar to other stimulants and include nervousness, dyspepsia, and rapid heart rate. Some side effects, such as dehydration and elevated blood pressure, are ameliorated by regular use.

- Pregnancy Category C

- Approximate doses of caffeine by source:6

- Coffee

- The highest doses of caffeine in coffee are found in light roasted robusta coffee beans. The roasting process actually removes the effective dose of caffeine that reaches your brain.

- An average 8oz cup of coffee typically contains approximately 100mg to 150mg of caffeine. Note that most “small” coffee sizes in the U.S. are actually 12oz or more.

- Energy drinks

- Multiple varieties are available.

- They come in a wide range of concentrations, from 10mg to 40mg per fluid ounce (check labels). Note that many drinks come in cans of 16 fl. oz. or more.

- Energy “shots” contain more caffeine per fluid ounce, typically 100mg per fluid ounce, or about ¾ of a standard shot glass.

- These products often have significant amounts of sugar added.

- Caffeine pills or tablets

- Multiple varieties available

- Typically contain 200mg of caffeine per tablet (check labels)

- Note that many weight-loss supplements contain significant amounts of caffeine

- Coffee

- Modafinil7

- Selective weak dopamine reuptake inhibitor, although the exact mechanism of action remains unknown

- 200mg once a day by mouth, taken 1 hour prior to the start of the work shift

- Official FDA indications for modafinil are narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, and shift work sleep disorder.

- Side effects (≥5%) can be similar to those of other stimulants and include headache, nausea, nervousness, anxiety, dyspepsia, and diarrhea.

- Pregnancy Category C

- Modafinil is a schedule IV drug, which means you’ll need a prescription. The FDA classifies schedule IV drugs as those with accepted medical uses in the U.S. and a low potential for abuse relative to schedule III drugs. Other schedule IV drugs include zolpidem, tramadol, and alprazolam.

- Armodafinil8

- Armodafinil is the R-enantiomer of modafinil.

- 150mg once a day by mouth, taken 1 hour prior to the start of the work shift

- Official FDA indications for armodafinil are the same as modafinil (narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, and shift work sleep disorder). Armodafinil was also approved in 2010 to treat jet lag.

- Although armodafinil and modafinil have similar half-lives, armodafinil reaches peak concentrations later, which may help people with excessive daytime sleepiness related to conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea.

- Side effects (5%) are similar to modafinil and other stimulants, including headache, nausea, nervousness, anxiety, dyspepsia, and diarrhea.

- Pregnancy Category C

- Armodafinil, like modafinil, is a schedule IV drug.

Sedatives

- Alcohol

- Although alcohol can help you to fall asleep more quickly, it changes the architecture of your sleep cycle, which can result in waking up in the middle of your sleep period or otherwise disturbed sleep.

- Alcohol proportionally decreases the amount of time spent in REM sleep and increases the time spent in Stage II sleep.

- Antihistamines (diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine)

- Many over-the-counter “sleeping pills” actually contain antihistamines as the active ingredient.

- Antihistamines cross the blood-brain barrier and block the H1 receptors in central nervous system, causing drowsiness.

- Common side effects include persistent drowsiness, flushing, and dry mouth.

- In overdose, antihistamines produce an anticholinergic toxidrome that can present as hallucinations, seizure, urinary retention, and in severe cases coma and death.

- Pregnancy Category A (totally safe in pregnancy)

- Melatonin9

- Melatonin is known as the “sleep hormone.” It is a naturally occurring hormone secreted by the pineal gland in the brain. Melatonin levels typically rise sharply late in the evening, signaling to your body that it is time for sleep. Levels stay high throughout the night for the next 12 hours before dropping. Daytime levels of melatonin are almost undetectable.

- Sunlight and other bright lights inhibit the release of melatonin (so if you are taking this medication after a night shift, be sure to put on a pair of sunglasses for the commute home).

- Melatonin supplements can be found over-the-counter at pharmacies and health food stores. Most commercial products contain dosages that will elevate melatonin to much higher levels than are naturally produced by the body, although there have been no reported effects of toxicity or overdose. Note that commercial production of melatonin is NOT regulated by the FDA and it is possible that a wide range of concentrations of active ingredient may exist between different products.

- Melatonin does not show any significant benefit in decreasing sleep latency compared to placebo in most randomized controlled studies. However, research does suggest a non-statistically significant trend toward improved sleep when melatonin is taken at the appropriate time for shift work and jet lag.

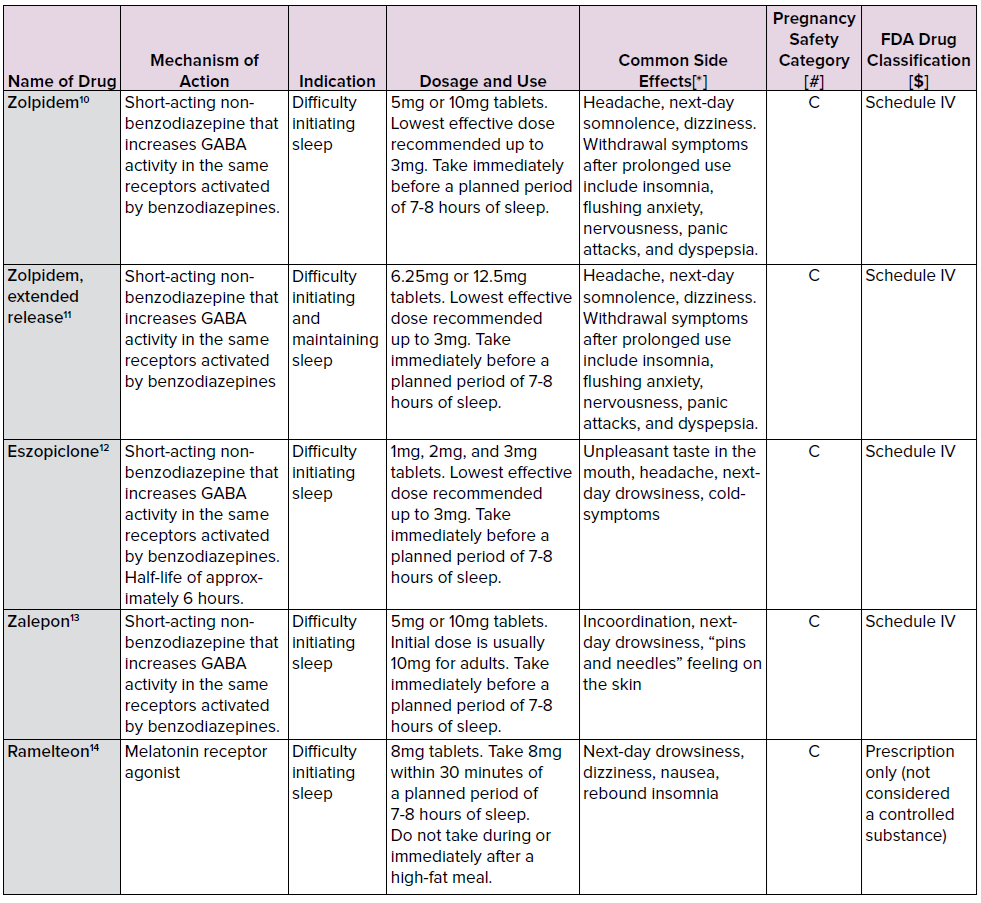

- Nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics (see table)

[*] Zolpidem, eszopiclone, and zalepon have been linked in rare cases to situations in which people have gotten out of bed and performed various activities while asleep, such as driving, making and eating food, talking on the phone, sleep-walking, and having sex.

[#] Risk of fetal harm not ruled out.

[$] You’ll need a prescription for any schedule IV drug. The FDA classifies schedule IV drugs as those with accepted medical uses in the U.S. and a low potential for abuse relative to schedule III drugs. Other schedule IV drugs include modafinil, tramadol, and alprazolam.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC AIDS

- Aids to create the ideal sleeping environment

- The ideal sleeping environment is cool, dark, and quiet.

- Sleep masks

- Blackout curtains

- Ear plugs

- Temperature control (fans, air-conditioning)

- White noise machines or recordings

- The ideal sleeping environment is cool, dark, and quiet.

- Sunglasses

- Release of the “sleep hormone” melatonin (see “Pharmacologic Aids - Sedatives”) is blocked in the presence of sunlight. Dark UV-blocking sunglasses worn before exiting the hospital can prevent the suppression of melatonin release and make falling asleep after a night shift easier.

- Blue light filters

- Similar to sunlight, many electronic devices such as smartphones, e-readers, tablets, computers, and televisions release high energy wavelengths of light that can send activating signals to the brain, making it more difficult to fall asleep.

- Special clear “blue light” filters designed to block these specific activating wavelengths are commercially available in a variety of forms, from screen protectors to sunglasses.

- Some newer smartphones are also coming with a “night time” option that filters blue light and decreases brightness; check your phone and activate this option.

- Light boxes

- Commercially available light boxes mimic the wavelength patterns of sunlight.

- Exposure to bright light first thing in the morning (or as soon as you wake up prior to a night shift) can help to set your circadian clock to signal “daytime.”

- Light is also used in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder.

- Exercise

- Exercise raises body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and activates the sympathetic nervous system.

- Regular exercise may improve sleep quality in general.

- Exercising first thing in the morning (or as soon as you wake up prior to a night shift) can help to set your circadian clock to signal “daytime.”

- However, vigorous exercise within 2 hours of bedtime can actually make it more difficult to fall asleep.

DROWSY DRIVING

The National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration (NHTSA) identifies both emergency personnel and shift workers as high-risk populations for drowsy driving. That means YOU. Drowsy driving is more serious than just feeling sleepy behind the wheel. The NHTSA estimates there are more than 72,000 police-reported crashes involving drowsy driving that injure more than 41,000 people and kill more than 800 each year.15 Not only do drowsy drivers place themselves at risk of harm, but they also jeopardize the lives of passengers, drivers, and pedestrians around them.

If you’re working nights or long hours, you might not be as alert as you think you are. When severely sleep-deprived, our body can experience “micro sleeps,” brief periods of unconsciousness lasting up to 5 seconds, that might not even register as falling asleep at all. You can travel more than 100 yards in 5 seconds while driving on the highway. Scary.

Although it’s clear that actually falling completely asleep while driving has deleterious consequences, research has shown that people who are sleep-deprived suffer cognitive delays on par with driving while intoxicated. Research using a driving simulator showed that subjects had a significant delay in reaction time and an increase in lane variability after being awake for 24 hours on a level comparable with a blood alcohol content of 0.10% - greater than the legal limit for alcohol intoxication while driving.16

The most common factors associated with a higher likelihood drowsy driving include:17

- Averaging less than 6 hours of sleep the previous night

- Driving for more than 3 hours

- Driving on an interstate type highway with a posted speed limit over 55mph

- Driving between 9 pm and 6 am

Drowsy driving warning signs:18

- Yawning, rubbing your eyes, or blinking frequently

- Trouble focusing, keeping your head up, or your eyes open

- Difficulty remembering the past few miles driven

- Drifting from your lane or hitting the rumble strip

- Slower reaction time, poor judgment

What you can do:

- Let someone else drive

- Especially if you live in a city that offers reasonable transport by bus, subway, or rail, consider taking public transportation to work. Even if you fall asleep on the ride home, at least you won’t be at risk of harming yourself or someone else.

- Call a taxi.

- Use a ride-sharing service. Many of them have a convenient app to make hailing an on-demand ride even easier.

- Have a buddy

- Consider carpooling with another person with the same schedule. Not only will you help save the environment, you’ll have someone in the car with you to help keep you awake and alert.

- Sleep before heading home

- Ask if your department or hospital has call rooms available. Take a 15-30 minute nap after your shift before driving home.

- If your hospital does not have call rooms, consider advocating for one.

- Seek out friends, colleagues, or family who live closer as another alternative for a nap before driving when you’re especially tired.

- Pull over

- If you find yourself nodding off, find a safe spot to pull over to the side of the road and take a 15-30 minute nap.

- Prioritize sleep (in general)

- Life is busy and sometimes it feels like the easiest thing to cut corners on is your sleep time. But being sleep-deprived not only makes it more difficult to get your tasks done properly, it can put you at serious risk of harm. Try to prioritize sleep as much as you can on a daily basis.

REFERENCES

- American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Clinical Policy on Emergency Physician Shift Work. https://www.acep.org/clinical---practice-management/emergency-physician-shift-work/. Updated June 2010. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Policy Education and Resource Paper: Circadian Rhythms and Shift Work. https://www.acep.org/Physician-Resources/Practice-Resources/Circadian-Rhythms-and-Shift-Work---PREP/. Updated October 2010. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Liguori A, Hughes JR, Grass JA. Absorption and subjective effects of caffeine from coffee, cola and capsules. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;58(3):721–6.

- Wyatt JK, Cajochen C, Ritz-De Cecco A, et al. Low-dose repeated caffeine administration for circadian-phase dependent performance degradation on extended wakefulness. Sleep. 2004;27(3):374-81.

- Dagan Y, Doljansky JT. Cognitive performance during sustained wakefulness: A low dose of caffeine is equally effective as modafinil in alleviating nocturnal decline. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(5):973-83.

- Center for the Science of Public Interest. Caffeine Chart. https://cspinet.org/eating-healthy/ingredients-of-concern/caffeine-chart. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Provigil Website. Full prescribing information for modafinil. http://www.provigil.com/pdfs/prescribing_info.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Nuvigil Website. Full prescribing information for armodafinil. http://www.nuvigil.com/PDF/Full_Prescribing_Information.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- National Sleep Foundation. Melatonin and Sleep. https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep-topics/melatonin-and-sleep. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Sanofi Website. Full prescribing information for zolpidem. http://products.sanofi.us/ambien/ambien.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Sanofi Website. Full prescribing information for zolpidem, extended-release. http://products.sanofi.us/ambien_cr/ambiencr.html. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Lunesta Website. Full prescribing information for eszopiclone. http://www.lunesta.com/PostedApprovedLabelingText.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Pfizer Website. Full prescribing information for zalepon. http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=710. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Rozerem Website. Full prescribing information for ramelteon. http://general.takedapharm.com/content/file.aspx?applicationcode=2bcc07ca-d9c0-4704-9a28-963127115641&filetypecode=rozerempi&cacheRandomizer=a4157174-2793-4481-9c2b-02bbac948ecc. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Transportation and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. NHTSA Drowsy Driving Research and Program Strategic Plan. https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.dot.gov/files/drowsydriving_strategicplan_030316.pdf. Published March 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Howard ME, Jackson ML, Kennedy GA, et al. The interactive effects of extended wakefulness and low-dose alcohol on simulated driving and vigilance. Sleep. 2007;30(10):1334-40.

- Royal D. Volume I: Findings from the national survey of distracted and drowsy driving attitudes and behaviors 2002 (Report number DOT HS 809 566). Gallup Organization and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. http://www.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/drowsy_driving1/survey-distractive03/summary.htm. Published April 2003. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- National Sleep Foundation. Drowsy Driving Prevention Fact Sheet. https://sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/3-Drowsy%20Driving%20Media%20One%20Sheet-CSG-FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2016.