Staying Safe on the Job

Chapter 6 Audio

INTRODUCTION

As emergency physicians, our daily job inherently involves interacting with a wide variety of people: patients, their families, myriad consultants, and our own department staff. The high acuity and stressful nature of our job is a breeding ground for all types of disagreements, which can potentially escalate into violence. Learning to recognize, appropriately manage, and stay safe in the face of conflict with others is a key skill in effectively practicing emergency medicine.

INTERPERSONAL CONFLICT

Although maintaining a patient-centered approach with consultants and developing rapport with patients is important, emergency physicians will inevitably run into conflict with both of these groups. While there is no “correct” way to manage these problems, we can be prepared to deal with any obstacle appropriately as long as we understand how to use the different tools at our disposal.

Types of Conflict Modes and When to Use Them

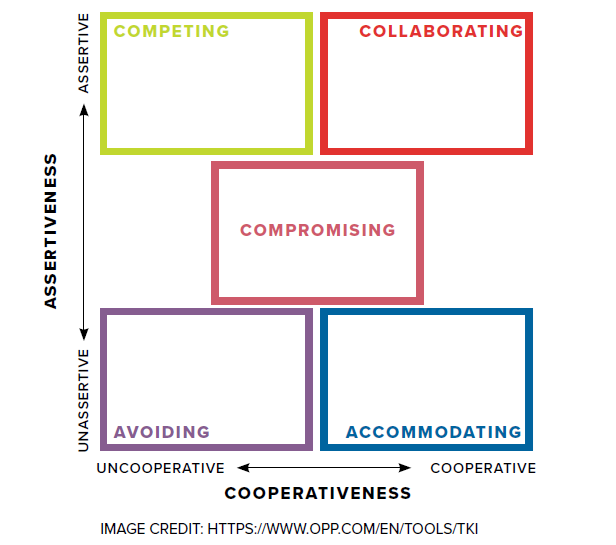

In conflict situations, our behavior can be mapped along two dimensions: assertiveness and cooperativeness. Assertiveness describes the extent to which we try to satisfy our own concerns, whereas cooperativeness describes the extent to which we try to appease others’ concerns. These two dimensions can then be used to define 5 different ways of handling a conflict situation. The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) is a self-administered questionnaire that assesses your tendency to use one conflict mode over another. (Find more at http://www.kilmanndiagnostics.com/catalog/thomas-kilmann-instrument-one-assessment-person.) The 5 conflict modes are summarized directly from the work of Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann.1

It is important to understand that one type of conflict mode is not inherently “better” than another. Rather, think of each conflict mode as being more or less appropriate for a particular situation. By understanding each of the different conflict modes as well as your own tendencies, you can leverage each of them in the most appropriate situation to achieve the best possible outcome for all parties involved.

Avoiding: Unassertive and Uncooperative

Avoiding essentially involves not addressing the key issue at hand. It can take the form of sidestepping an issue, holding off on performing a duty that can be delayed, or ignoring a problem altogether. However, avoidance can be a useful tool in certain situations. For example, trying to repetitively prove a point with a family member who is overtly hostile or dangerous may not be the best approach in that moment. It may be more appropriate in this case to calmly inform the family member that you will step away until a more appropriate discussion can be held.

Accommodating: Unassertive and Cooperative

This conflict mode involves an element of self-sacrifice and occasionally self-neglect. It can often result in “giving more than taking.” Accommodating in the ED commonly manifests as giving in to an attending physician’s requests, even if you don’t agree with the management plan. Similarly, this can be seen in some interactions with consultants. On the other hand, accommodating can also manifest as selfless generosity to strangers, such as staying late after a shift to ensure that a patient is safely reunited with his or her family.

Competing: Assertiveness and Uncooperative

Competing involves asserting your own beliefs regardless of others’ needs. It is a power-oriented (or “bully”) mode of approaching conflict. Strongly advocating for a consultant to come to the ED immediately to evaluate a patient you believe is critically ill or refusing to give opiates to a patient with an extensive history of drug seeking behavior are appropriate instances of implementing a power-oriented conflict management mode.

Compromising: Intermediate Assertiveness and Cooperativeness

Compromising falls in the middle of the spectrum of both assertiveness and cooperativeness. When using a compromising conflict mode, your goal is to find a solution that partially satisfies both parties, which also means that neither party is fully satisfied with the result. Compromising might mean splitting the difference. For example, you want your consultant to come immediately to the ED from home, but your consultant wants to wait until morning; you split the difference and she arrives in 3 hours. Compromising can be useful, however, for seeking a quick middle-ground resolution to a problem.

Collaborating: Assertive and Cooperative

In contrast to compromising, collaborating involves finding a solution that is mutually beneficial to both parties. It can involve digging deep into issues in order to resolve underlying problems, understand each other’s perspective, or find a creative solution. For example, an ideal time to collaborate would be in situations that involve shared decision-making. However, while collaboration may seem like the ideal way to handle conflict all the time, it is certainly not appropriate in all situations. For example, getting involved in an in-depth discussion about the pros and cons of continued epinephrine administration while a patient is in cardiac arrest is not appropriate.

Conflict with Consultants

We deal with consultants on every shift. Many times these interactions are straightforward and our patients are seen by specialty services in a timely manner. But sometimes we don’t agree with the physicians on the other end of the phone line. These disagreements range from refusal to evaluate patients (“inappropriate consults”) to management or disposition recommendations that – to us – don’t appear to be in our patients’ best interest. Managing conflicts like this can be frustrating and time-consuming. A helpful construct for framing these conflicts is the DESC Script, described in Chapter 3: Rapid Team-Building.

At the end of the day, however, you are charged with the responsibility of caring for your patients. Whenever possible, maintain a patient-centered view.2 It is often far more constructive to frame disagreements with consultants in terms of benefit to the patient rather than benefit to yourself. Consider the 5 conflict modes at your disposal and select the mode that would achieve the best possible outcome for your patients at the moment a conflict arises.

Conflict with Patients and Families

First impressions last forever. Developing early rapport with patients and their families is important and will positively affect the health of your patient as well as your own work satisfaction.3,4 One of the most effective things you can do to prevent conflict is to set expectations.5 Approximate timelines for testing and imaging, pain management, and establishment of follow-up are factors that, if explained properly, are avoidable sources of conflict.6,7 Take a few extra minutes in the patient encounter and you can create more fulfilling experiences for your patient, his/her family, and yourself.

WORKPLACE VIOLENCE

Recognition: What is Workplace Violence?

Workplace violence (WPV) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “incidents when staff are abused, threatened, or assaulted in circumstances related to their work, including commuting to and from work, involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being, or health.” Workplace violence can be divided into the categories of physical violence and psychological violence. Other terms that are often used interchangeably with WPV include assault or attack, abuse, bullying, harassment (including sexual and racial harassment), and threats.8

How Prevalent is Workplace Violence?

The ED is well-cited in the literature as the health care setting with the highest incidence of workplace violence.9 Prior studies have examined the prevalence of WPV and subtypes of WPV in the ED in a multitude of countries and with different types of staff, including nurses, EMS workers, and physicians. The results are concerning. One study that involved physicians, nurses, and medical technicians found that 96% of staff had experienced an incidence of violence while at work in the ED.10 Other studies found lower rates of 78% (resident physicians, number who had experienced at least one episode of WPV), and 37% (resident physicians, number who had experienced an episode of physical violence committed by patients or visitors).11

Workplace Discrimination

A discussion of WPV is not complete without acknowledging the presence of discrimination in the workplace. The specific focus here will be on discrimination on the part of patients and visitors against ED staff. This is a complex topic and a part of a greater discussion outside the scope of this chapter that should be continued in our community. WPV is linked with, and can lead to, discrimination. Discrimination is defined by the WHO as, “any distinction, exclusion, or preference which has the effect of nullifying or impairing equality of opportunity or treatment … such as those made on the basis of race, color, sex, religion, political opinion, national extraction, or social origin.”8 When workplace discrimination occurs, the first step is to identify the behavior or attitude as discrimination. This identification is important in order to ensure that staff understand these actions are inappropriate and harmful. The next step is to provide staff with resources for the reporting of the incident and support for those managing the aftermath of discrimination. In addition to having the appropriate mechanisms in place to manage these incidents after they occur, the provision of a clear and deliberate statement of support for staff and a no-tolerance policy of discrimination is key.

Risk Assessment

Environmental

One common environmental condition that puts a health care setting at risk for WPV is one that is understaffed and has insufficient resources. Having prior episodes of WPV or crime is another environmental risk factor for WPV. In addition, working alone or in isolation in a setting can place a health care worker at risk.8

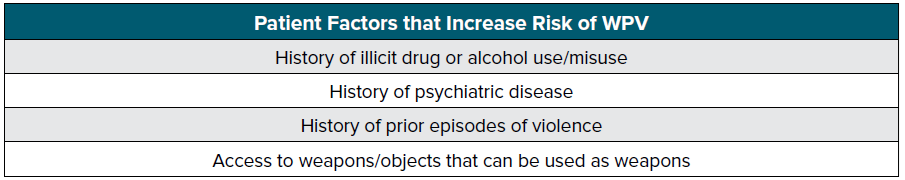

Patient-Based Characteristics

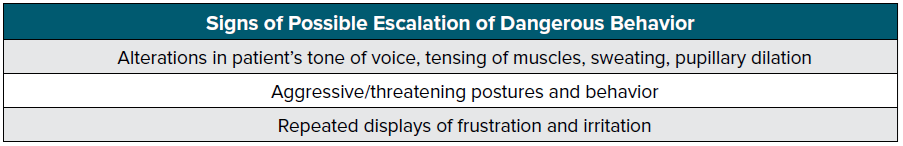

Prior studies have described patient factors that contribute a propensity toward violence. The accompanying table, adapted from Schnapp et al, 2016,11 displays patient factors that can foreshadow WPV, as well as signs of a potential impending incident.

In 2005 Luck and colleagues developed a framework nurses could use to identify patients at risk for violence.12 The framework was described by the acronym STAMP:

- Starting and eye contact

- Tone and volume of voice

- Anxiety

- Mumbling

- Pacing

Following are signs of a potential impending incident, adapted from the WHO Framework Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence in the Health Sector.8

Intervention: De-escalation and Other Techniques

When an episode of WPV is judged to be impending or is actually happening, staff must be provided with the appropriate tools to prevent further deterioration of the situation. Prior studies have found that 14-16% of EM residents reported training in violence prevention or de-escalation techniques.11

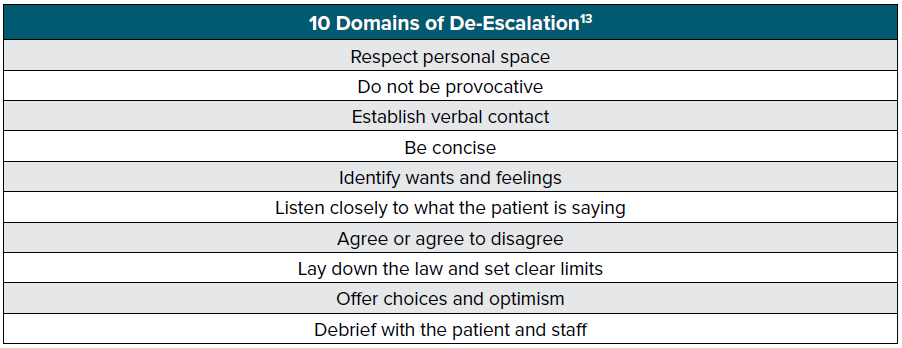

If you do find yourself in a violent or threatening situation, you can follow the non-coercive de-escalation techniques described below to potentially diffuse the situation. These techniques require you be aware of to your tone of voice, word choice, and body language. When you engage a patient in conversation, you should introduce yourself, address the patient directly, and state that you want to assist them in regaining control of their behavior.

The main principle of non-coercive de-escalation is to create a “verbal loop” in which the clinician listens to the patient’s concerns, responds in a way that either agrees or validates the patient’s response, and then states what they want the patient to do.13 Only one person should engage the patient verbally in a situation in order to prevent confusion and further escalation of threatening or violent behavior.13 It is important to avoid the use of defensive, provocative, or contradictory language.14 It may take multiple iterations of the verbal loop to successfully calm the patient. 13 If the situation escalates further, you should maintain non-threatening eye contact, keep hands open and visible, and use nodding to signify understanding when the patient is speaking. With regard to your body language, respect the patient’s personal space (2 arms’ length distance away from the patient), avoid physical contact with the patient, and when approaching the patient, do so at an angle or from the side. 14

If the patient loses control of his/her behavior, you must proactively protect yourself, other staff, and other patients in the department. Ensure that you and any other involved staff are near an exit. Clear the space of patients, and enlist the assistance of your hospital’s security staff. Prior to this you may try to use limit setting, which uses “a command form to express the desired behavior, and provides logical and enforceable consequences for noncompliance.” 14 One example of this is, “Please return to your stretcher and stop yelling. I don’t want to involve security, but I may have to if you can’t control yourself.”

Aftermath: Reporting, Quality Assurance, and Coping

The impact of patient-related WPV can affect an individual physically and emotionally, as well as have an impact on their career and education. It is imperative that after an episode of WPV the appropriate steps are taking to report the incident and protect and support the affected individual.

Any incident of physical or psychological violence should be reported and recorded. Trainees should report to the supervising attending physician, and then to the appropriate institutional reporting system.

Debriefing after the incident with all staff involved is necessary in order to provide staff with time to reflect on and process the incident. The debriefing will allow the safe space for providers to process their reactions to a case. After the impact realization of the event, the involved providers will likely experience a mix of emotions, and may experience recurrent thoughts about the incident and repeated re-evaluate the situation in their minds. Debriefing may occur at multiple time periods (hot, warm, and cold debriefs) depending on the situation. Staff support networks and institutional counseling services should be made available to all staff.

On both the departmental, institutional, national, and international level, episodes of WPV should be tracked. More locally, individual institutions or departments should periodically review reports of WPV and provide plans for improvement of staff and patient safety.

References

- Thomas KW, Kilman RH. An Overview of the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument. Kilmann Diagnostics. http://www.kilmanndiagnostics.com/overview-thomas-kilmann-conflict-mode-instrument-tki. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- Greene SM, Tuzzio L, Cherkin D. A Framework for Making Patient-Centered Care Front and Center. Perm J. 2012;16(3):49-53.

- Schneider J, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Li W, Wilson IB. Better Physician-Patient Relationships Are Associated with Higher Reported Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Patients with HIV Infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1096-1103.

- Szecsenyi J, Goetz K, Campbell S, Broge B, Reuschenbach B, Wensing M. Is the job satisfaction of primary care team members associated with patient satisfaction? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(6):508-514.

- Berhane A, Enquselassie F. Patient expectations and their satisfaction in the context of public hospitals. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1919-1928.

- Tenbensel T, Chalmers L, Jones P, Appleton-Dyer S, Walton L, Ameratunga S. New Zealand’s emergency department target – did it reduce ED length of stay, and if so, how and when? BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:678.

- Kilmann RH, Thomas KW. Four Perspectives on Conflict Management: An Attributional Framework for Organizing Descriptive and Normative Theory. Acad Manage Rev. 1978;3(1):59–68.

- International Labour Office (ILO), International Council of Nurses (ICN), World Health Organization (WHO), Public Services International (PSI), Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. (2002). Framework Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. ILO, ICN, WHO, PSI, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Mentzel T, Al-Natour A, Kowalenko T. Evaluation of a Comprehensive ED Violence Prevention Program. J Emerg Nurs. 2013;39(4):376-383.

- Touzet S, Cornut PL, Fassier JB, Le Pogam MA, Burillon C, Duclos A. Impact of a Program to Prevent Incivility Towards and Assault of Healthcare Staff in An Opthalmological Emergency Unit: Study Protocol for the PREVURGO On/Off Trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14: 221.

- Schnapp BH, Slovis BH, Shah AD, Fant AL, Gisondi MA, Shah KH, Lech CL. Workplace Violence and Harassment Against Emergency Medicine Residents. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(5): 567-573.

- Luck L, Jackson D, Usher K. STAMP: Components of Observable Behavior that Indicate Potential for Patient Violence in Emergency Departments. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59(1): 11-19.

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, Holloman Jr GH, Zeller SL, Wilson MP, Rifai MA, Ng AT. Verbal De-escalation of the Agitated Patient: Consensus Statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1): 17-25.

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). https://wwwn.cdc.gov/wpvhc/Course.aspx/Slide/Unit7_1 August 12, 2013. Accessed on October 13, 2017.