Fixing Violence in the Emergency Department

Fixing Violence in the Emergency Department

Benjamin J. DeYoung, MPH, OMS-IV,

Kansas City University College of Osteopathic Medicine

EMRA MSC Content Coordinator

Edited By:

Olivia Voltaggio, OMS-IV,

Rocky Vista College of Osteopathic Medicine - SU

EMRA MSC Editor

Less than one month ago, a patient at Endeavor Health Evanston Hospital in Illinois produced a gun while frustrated with the intake process and fired several rounds during an altercation, injuring a security guard1. This marked the latest incident of severe violence within the walls of American emergency departments (EDs), which experience a heavy volume and wide spectrum of violence annually. To the outsider, incidents like these are an outrage, however, to ED staff across the United States, violence is an unacceptable yet tragically common reality in the workplace.

The ED exists in the nebulous space between first responders in the field and inpatient hospital care. Healthcare is, as an entity, already susceptible to unprecedented levels of workplace violence2; however, the ED's unique station provides much more opportunity for violence to occur, often in unpredictable ways. From psychiatric encounters to medical emergencies, patients present acutely delirious, agitated, combative, or upset, leading them to act physically and verbally violent towards ED staff. Some patients have been the immediate victims of violence before their arrival. For other patients and family members, their acute, untreated pain causes tempers to flare. Overcrowding, hospital equipment that can be used as weapons, and lack of privacy also turn the heat up on violence in the ED3. So what can we do about this glaring problem?

ED Violence Facts

First, we need to understand the ubiquity of the problem and the barriers to addressing it. 91% of resident and attending physicians have identified themselves or a colleague as the recipient of violence in the ED, with 85% saying violence has increased in the past five years4. Nurses are similarly susceptible to violence5. To any ED worker, those numbers seem laughably low. Therein lies a key problem with ED violence reduction: reporting. For a multitude of reasons, only 30% of nurses and 26% of physicians adequately report incidents of violence, owing to malignant healthcare culture or complacency with thinking that violence “is just a part of the job.”2 1 in 5 workers indicate that being the victim of ED workplace violence has affected the ability to perform their job; 1 in 5 ED workers indicate PTSD symptoms; and half of ED workers feel violence has permanently changed how they interact with or perceive their patients6. These statistics paint the picture: ED staff are relentlessly exposed to violence, even to the detriment of their long-term well-being, but often refrain from speaking up to change the culture.

What We Can Change: Structure and Culture

Two themes have been highlighted in the literature to address ED violence: fixing structural problems and fixing cultural problems.

Structural problems are the physical contributors to ED violence, such as security coverage and protocols, weapons screening, department layout, and hospital policies. While the majority of EDs have adequate security staff at points of entry7, the vast majority of violence occurs in examination rooms (58%), observation areas (24%), and triage (11%), often after standard working hours8. This highlights the need for security to be present where and when the majority of incidents occur, rather than responding after the fact. In addition, standardized weapons screening has been reported in as little as 40% of EDs7. This practice should be instituted nationwide; implementing passive weapons screening like metal detectors has significantly increased the safe removal of weapons from the clinical environment9,10. Despite split hospital perception on the optics of passive weapons screening, the literature has shown the public is amenable to the practice while it removes unknown tools for violence from the exam room10. Similarly, any hospital policies that do not prioritize the safety of clinicians should be challenged, and unsafe layouts to ED workflow should be identified promptly.

Culture problems represent a more substantial hurdle for ED violence prevention. Although strides have been made towards changing the perception of violence as “part of the job,” reporting incidents remains a key priority. A low threshold for reporting is essential, as ED workers tend to overlook minor incidents2. Also, ED staff should be vigilant about their attitudes and working conditions to ensure that violence in the environment does not bleed over to caring for other patients. Advocacy at both the institutional and national levels are important to shifting into a safer ED culture and preventing burnout. “Zero tolerance” is often espoused by health systems, but is far from a reality. To speak up, get involved here 11.

Final Thoughts

Experiencing physical and verbal violence in the ED is unfortunately commonplace for all ED workers. It is difficult to tackle, but effective prevention tools exist. They should be implemented without hesitation. Advocating for better working conditions is not only essential to providing every patient with great care—it reduces the mental and physical burden of workplace violence on ED workers. It is time to change the culture for good.

References

1. Evanston man charged in hospital emergency room shooting, police say. Chicago tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/2025/06/10/evanston-man-charged-in-evanston-hospital-shooting-police-say/. June 10, 2025. Accessed June 24, 2025.

2. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1661-1669. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1501998

3. Stowell KR, Hughes NP, Rozel JS. Violence in the emergency department. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):557-566. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.07.003

4. Violence in the emergency department: Resources for a safer workplace. ACEP.org. Accessed June 24, 2025. http://acep.org/administration/violence-in-the-emergency-department-resources-for-a-safer-workplace/

5. Chazel M, Alonso S, Price J, Kabani S, Demattei C, Fabbro-Peray P. Violence against nurses in the emergency department: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(4):e067354. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067354

6. McGuire SS, Finley JL, Gazley BF, Mullan AF, Clements CM. The team is not okay: Violence in emergency departments across disciplines in a health system. West J Emerg Med. 2023;24(2):169-177. doi:10.5811/westjem.2022.9.57497

7. Behnam M, Tillotson RD, Davis SM, Hobbs GR. Violence in the emergency department: a national survey of emergency medicine residents and attending physicians. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(5):565-579. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.11.007

8. Oztermeli AD, Oztermeli A, Şancı E, Halhallı HC. Violence in the emergency department: What can we do? Cureus. 2023;15(7):e41909. doi:10.7759/cureus.41909

9. Malka ST, Chisholm R, Doehring M, Chisholm C. Weapons retrieved after the implementation of emergency department metal detection. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(3):355-358. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.04.020

10. McGuire SS, Gazley BF, Mullan AF, Clements CM. One year of passive weapons detection and deterrence at an academic emergency department: A mixed-methods study. Am J Emerg Med. 2025;89:57-60. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2024.12.021 11. No silence on ED violence. No Silence on ED Violence. Accessed June 24, 2025. https://stopedviolence.org/

Related Content

May 02, 2023

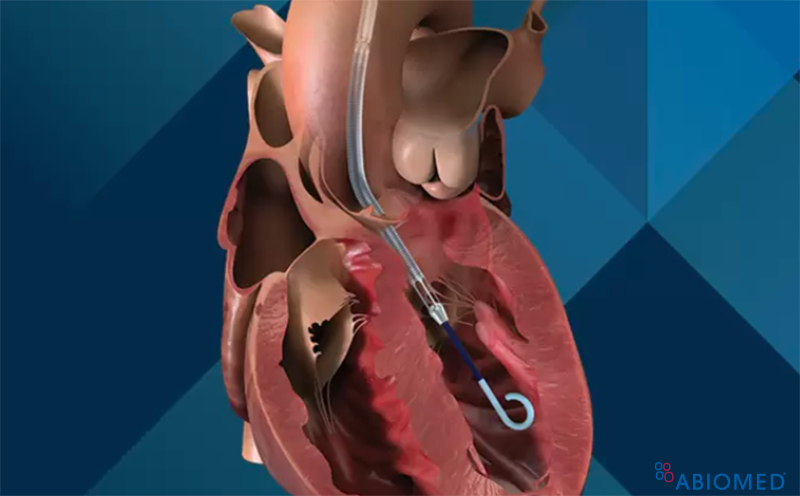

Critical Care Device Series: Impella®

Mechanical circulatory devices continue to evolve, allowing greater support of the sickest patients. This article discusses the Impella heart pumps, developed to address high-risk percutaneous coronary interventions, cardiogenic shock, right heart failure, left ventricular support, and more.

Jun 26, 2024

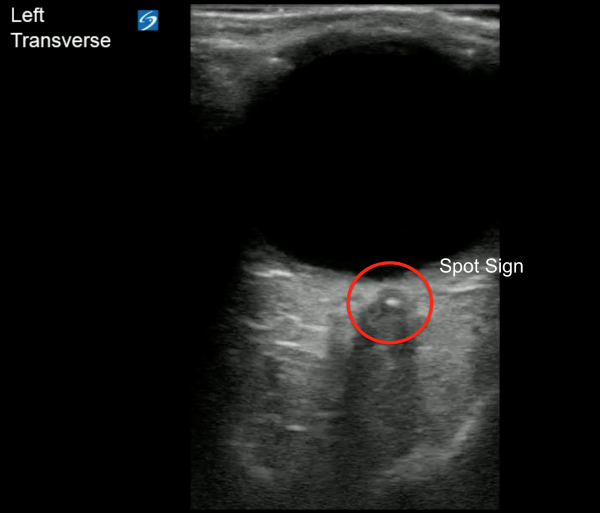

POCUS for the Win: Retrobulbar Spot Sign

Central retinal artery occlusion is an ocular emergency that commonly presents as sudden, painless, monocular vision loss. It can be a harbinger of serious comorbidities, making diagnosis important. POCUS has shown to be a quick and easy way to diagnose CRAO in the emergency department.