Ch 18. MVC: Blunt Trauma

At 08:15, paramedics are called to the scene of a construction site on

a major highway, where a 36-year-old male has been crushed against the median by a semi-truck. Access to the site is complicated by block- age of 2 of the highway’s 3 lanes during morning rush hour traffic.

Police have secured the scene, and traffic is stopped. The semi-truck has been moved away from the scene. On arrival, the patient is lying face-up on the asphalt, minimally responsive and surrounded by his concerned, shouting co-workers. His breathing is severely labored, and there is blood coming from his mouth. He is moaning, his face and neck are purple, and he has obvious fractures of both legs. The foreman knows little about the patient’s health other than he’s a smoker and rarely misses work. No one has been able to contact the patient’s wife, but efforts are continuing.

Scene Safety

Local law enforcement, fire, and EMS will be first to the scene of a motor vehicle collision (MVC). Before addressing the victims of the crash, it is essential the scene be assessed for safety. You must also anticipate any potential risks, including:

- Weather

- Flooding Fire/gasoline

- Chemical Spills

- Power lines

- Traffic

- Onlookers

Traffic should be rerouted and the scene blocked off before assessment can begin. EMS should wear appropriate protective and reflective gear that allows for full body movement. Once the scene is secure, triage and stabilization for transport can begin.

Fire will begin extricating victims trapped in vehicles. Be mindful of maintaining C-spine precautions when appropriate.

Remain Alert to Your Surroundings at all Times

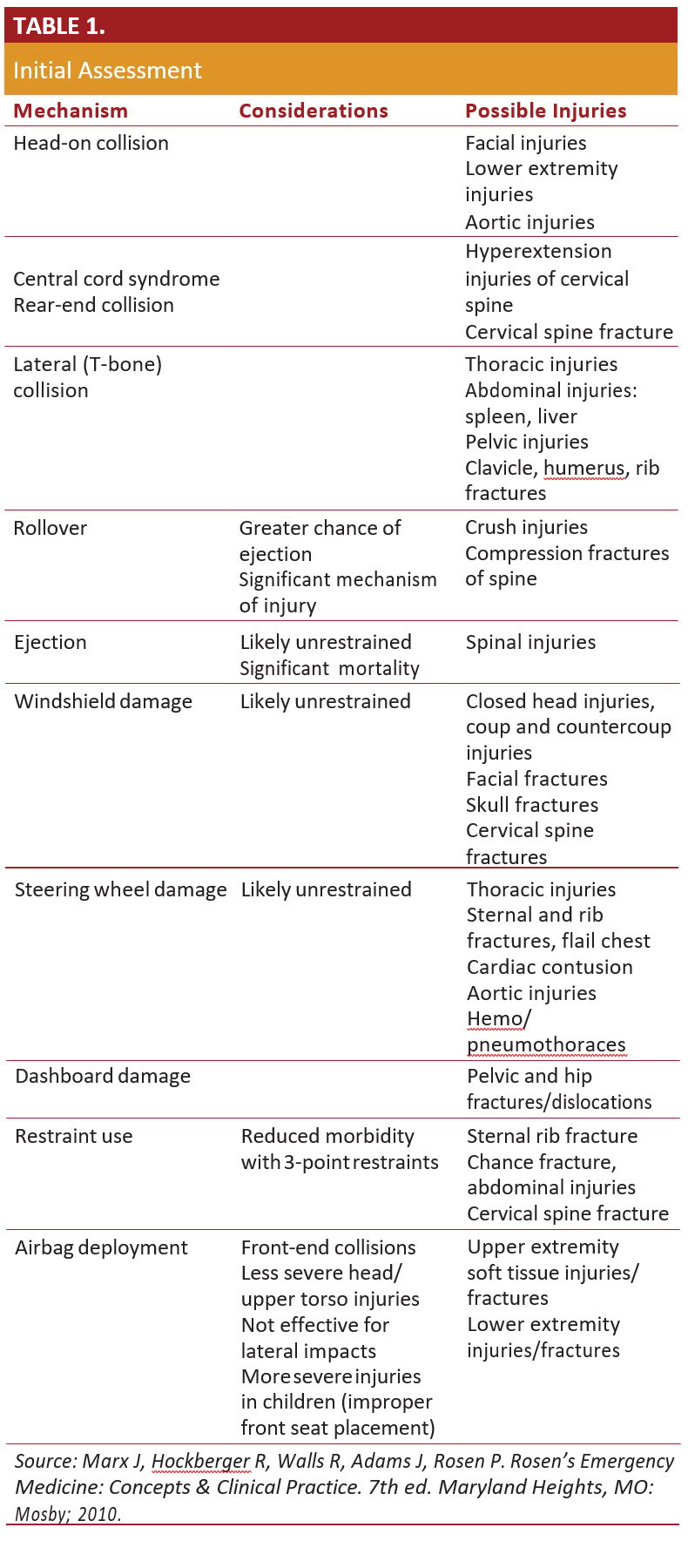

Initial Assessment

In an MVC, the speed of the vehicles involved, ejection of pas- sengers, the use of restraints, and need for extrication all can affect severity of injury.1 Recall Newton’s Laws of Motion. Rapid deceleration, crushing, and ejection all produce significant forces on the body both internally and externally.2,3 Therefore, not all injuries are obvious.

Assessment of the patient should proceed with mechanism of injury in mind. (Table 1.)

REMEMBER YOUR ABCs

Initial assessment of the patient at the scene is ABC:

A – AIRWAY

Ask a simple question, such as “Can you tell me your name?” If they do not respond, are there signs of obstruc- tion or noisy breathing? Jaw-thrust to open the airway. Try repositioning if needed. If the jaw-thrust doesn’t work, use the head tilt–chin lift method.4 Use suction as needed. If the airway is clear, can the patient maintain it on his or her own? If not, insert an airway adjunct. Take care with patients with facial fractures, as the airway may be harder to manage. Maintain spinal precautions where possible. Avoid over-extension of the neck during ventilation and intubation4 and place a C-Collar where indicated.

B – BREATHING

If the patient is responsive but not breath- ing adequately, give high-flow oxygen and be prepared to help ventilate if needed. If the patient is unresponsive and breathing adequately, place the appropriate adjunct or assess for intuba- tion. Give high-flow oxygen. If the patient is unresponsive and not breathing adequately, place an adjunct and provide ventila- tion with a bag-valve-mask (BVM) device using high-flow oxygen. Any signs of inadequate breathing should prompt an immediate examination of the chest.4 Flail chest (independently moving segment of chest wall) or lack of breath sounds that suggest pneumothorax require immediate intervention.5

C – CIRCULATION

A patient who is responsive and/or breathing adequately will likely have an intact pulse. Check the radial for at least 5 seconds. If you cannot feel a pulse, check the carotid site. If any doubt exists, begin compressions and prioritize transport. If a pulse is present, how is your patient’s overall perfusion? Look for major bleeding and control it. Assess the patient’s skin, noting color and condition. If the patient is a child, use the brachial site to check a pulse. Check capillary refill. It should be less than 2 seconds in adults and children.6 Pregnant patients (advanced trimester) may need to be tilted to the left on the backboard to facilitate venous return.7

Certain mechanisms of injury indicate a priority patient, no matter how minor the injuries seem to be. Regardless of injury, any patient who has been fully or partially ejected from a vehicle, was in the same vehicle as someone who died, or was in the path of significant intrusion should be considered a priority patient. Pedestrian, bicyclists, and motorcyclists with an impact speed over 20 mph also fall into this category. Also consider age; the very young and very old are unable to compensate and may deteriorate quickly with seemingly minor injuries.7 Older adults may have decreased pain perception that can mask the severity of an injury.8 With priority patients, a detailed exam can be done en route. If the patient is not a priority, you can proceed with a focused history and physical exam at the scene.

Injuries that Indicate a Priority Patient:

- Poor general impression

- Unresponsive or altered mental status

- Airway compromise

- Inadequate or difficult breathing

- Inadequate perfusion or shock, including cardiac arrest

- Severe bleeding that can’t be controlled

Transport

Once en route, EMS notifies the receiving transfer center/ED of basic details:

- Patient age and sex

- Mechanism of injury

- Vital signs

- Apparent injuries

- IV access

- Interventions performed: intubation, needle thoracostomy Early notification enables emergency department staff to prepare for the patient’s needs:

- Notifying additional teams (eg, trauma surgery, orthopedics, neurosurgery, obstetrics)

- Anticipate procedures (eg, intubation, chest tube, thoracotomy)

- Blood transfusion (eg, Central line, rapid volume infuser, O negative PRBC)

REASSESS THE PATIENT FREQUENTLY; PATIENT STATUS CHANGES QUICKLY.

While in transit, a paramedic notices the patient has stopped moving, and pulse oximetry is now declining. The blood pressure cuff is currently cycling. While there is a tracing on the monitor, a carotid pulse check reveals PEA arrest. The paramedic alerts the team, and CPR is initiated at 8:47 as EMS arrives at the ED. CPR continues as the patient is wheeled into the trauma bay.

Once at the ED, information should be communicated to the receiving staff or trauma team leader in a clear and succinct manner. In addition to any history obtained, the following should be included if applicable:

- Seat belt use

- Steering wheel deformation

- Airbag deployment

- Direction and speed of impact

- Damage to the vehicle (especially intrusion)

- Distance ejected

- Height of fall

- Body part landed upon

- Death of other passengers

Assessment begins anew by the receiving team even during the handoff. Reassessment is essential in blunt trauma, as the variety of injuries can manifest in countless ways. Stability of the patient is dependent upon the vigilance of the treatment team. Clear communication and the maintenance of a calm environ- ment facilitate successful treatment in critical trauma situations.

Upon arrival, report was quickly given, and resuscitation continued. Adequate access had already been established. The patient was intu- bated and had a chest tube placed for pneumothorax during the initial assessment with spontaneous return of circulation. Such an outcome wouldn’t have been possible without the critical assessment skills and the efficient action of all personnel.

References

- Lerner EB, Shah MN, Cushman JT, et al. Does mechanism of injury predict trauma center need? Prehosp Emerg Care. 2011;15:518.

- Wanek S, Mayberry JC. Blunt thoracic trauma: flail chest, pulmonary contusion, and blast injury. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20:71.

- McGwin G Jr, Reiff DA, Moran SG, Rue LW 3rd. Incidence and characteristics of motor vehicle collision-related blunt thoracic aortic injury according to age. J Trauma. 2002;52:859

- Hobgood C, Croskeery P, Wears RL, Hevia A. Patient safety in emergency Medicine. In: Tintinalli J, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS, eds. Emergency Medicine: a comprehensive study guide, 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2004: 1912-1918.

- Wanek S, Mayberry JC. Blunt thoracic trauma: flail chest, pulmonary contusion, and blast injury. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20:71.

- Chapman DM, Char DM, Aubin CD. Clinical decision making. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM. Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby; 2002: 107-115.

- Gross E, Martel M. Multiple trauma. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, et al., eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 7th ed.Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2010.

- Chapman DM, Char DM, Aubin CD. Clinical decision making. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM. Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby; 2002:107-115.