Ch 6. Subspecialty: Mass Gathering, Mass Casualty Incidents, and Incident Command

Mass Gathering

Mass gatherings, recognized as events with relatively large numbers of people, are becoming more frequent. These scenar- ios present unique problems for health care provision and safe- ty. These differences arise from a high concentration of people, often within venues that have limited or defined space.

Challenges

- Access to traditional EMS can be difficult.

- The resources present can be quickly overwhelmed.

- At a mass gathering, there is a higher incidence of people requiring medical care than the same population in the general public.

Planning

Large gatherings require deliberate planning, with careful at- tention to detail. Take into consideration:

- Venue size, layout, number of attendees/density, location, and expected weather.

- Venue entrance(s)/exit(s) and access.

- Social environment: Alcohol sales or consumption, drug use, access to water.

- Population: Elderly, young adults, children, and type of crowd (eg, dignitaries with security teams, etc.).

- Best models are previous events - ideally at the same venue and same previous event. This is often not available, so events similar in scope and population must be used as a comparison.

Providing Care

The role of a resident in a mass gathering event can vary. Keys to understanding your role:

- Know who is charge of medical care (local EMS, Red Cross, hospital, volunteer organization, etc.).

- Be aware of local legislative regulation for the particular region.

- Know the method of communication (dedicated radio systems, phones, etc.).

- Familiarize yourself with patient tracking and medical records system. This is important for patient care and planning future events.

- Understand the scope of patient care, drugs, and resources available.

- Consider methods of patient transport (gurney, carrying, golf carts, ambulances, etc.).

- Insurance coverage: Most events are planned well ahead of time. In these situations, the Good Samaritan law is often void. Determine the level of insurance coverage needed and adjust accordingly.

Unique Events Airline travel

- Most common complaints: Gastrointestinal, abdominal pain, and nausea/vomiting.

- Most serious complaints (aircraft can divert): Cardiac (MI), respiratory (PE), and neurological (stroke) complaints.

- Every airline has 24/7 physician consultation availability via satellite phone or radio.

- A medical provider can request to increase cabin pressure or descend to a lower altitude.

- Unique environment: Dry air, lower partial pressure of oxygen, potential virulent airborne particles, potential chemical irritants, and venous stasis.

Wilderness Events

- Considerations: Extreme temperatures, possible severe weather, risk of providers becoming patients, remote access creates problems with extrication.

Cruise Ships

- Considerations: Isolated and dense population, often high- morbidity patients.

- Most common complaints: Dyspnea and injuries.

Ultradistance Events

- Considerations: Location (city, wilderness, etc.), hydration status, and electrolyte abnormalities.

- Develop a plan for rehydration and electrolyte replacement, including use of PO vs. IV and possible use of hypertonic saline.

Mass Casualty Incidents

Mass casualties are chaotic situations in which multiple casualties are present. They can occur at mass gatherings, workplaces, highways, or any other location in which multiple people are present. The needs of the patients usually outweigh the resources available. Consequently, the goal of care becomes the greatest good for the greatest number.

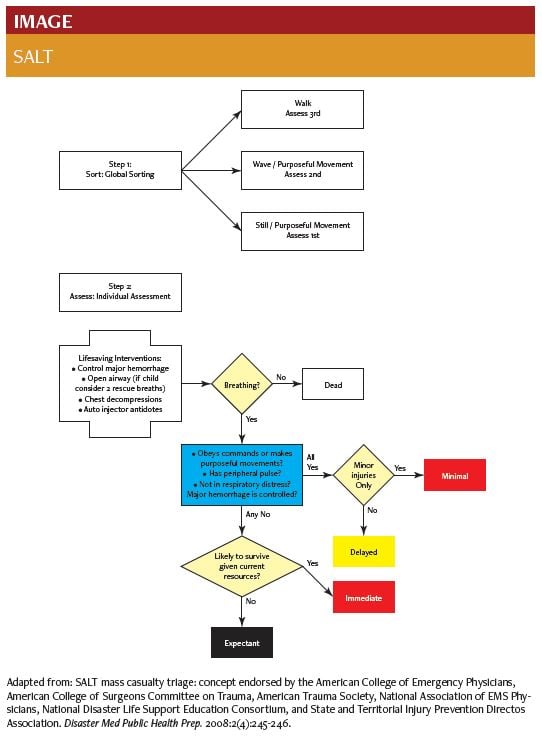

These challenges necessitate the use of a triage method to determine the order in which patients are addressed. Multiple triage methods can be used for mass casualties. A federally funded committee was appointed to evaluate the evidence pertaining to mass casualty triage and develop the Model Uniform Core Criteria, a set of requirements to ensure interoperability regardless of the triage system used. The resulting algorithm is called SALT: Sort, Assess, Lifesaving intervention, Transport. It is a nonproprietary triage scheme that meets Model Uniform Core Criteria and is used in some communities. It is important to understand what triage algorithm is used in your community.

Global Sorting

- Instruct those who can walk to move to a designated area. Assess last. They exhibit cerebral perfusion and essentially intact motor function.

- Instruct those who can hear but cannot walk to wave. These patients exhibit cerebral perfusion but have some other injury or situation. Assess second.

- Those who do not walk or wave need to be assessed first. They most likely have the most serious, time-sensitive injuries.

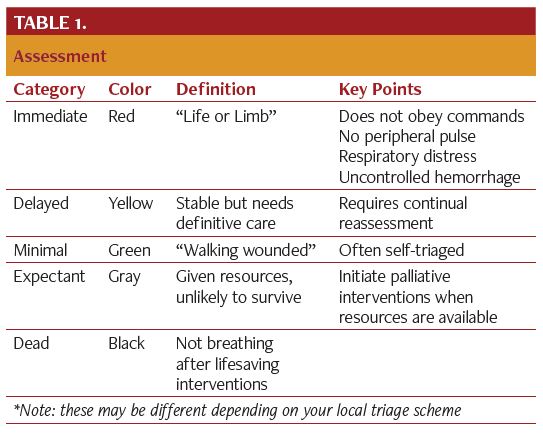

Assess

Patients are given a color corresponding to their need for treatment. A system will be in place to designate the color and record any intervention. This could range from commercially available cards to a marker on patient’s head or skin.

Provide Lifesaving Interventions

- Performed simultaneously with assessment.

- Controlling hemorrhage (tourniquet, direct pressure, etc.).

- Needle thoracostomy for tension pneumothorax.

- Autoinjector medications.

- Two rescue breaths may be given to children due to higher incidence of respiratory-related arrest.

- Not recommended: Chest compressions, intubation, bag- valve-mask ventilation.

- If patient is not breathing in the field, s/he is effectively considered dead.

Transport

- Largely incident command dependent.

- Those transported first are those who have the highest likelihood of survival given more interventions.

Mistakes to Avoid

- Considering triage complete: Patients require reassessment.

- Providing inappropriately complex care: Keep decisions and interventions within the scope of time and resources.

- Forgetting about the expectant patients: Enact palliative measures (eg, pain control) as more resources become available.

Incident Command System

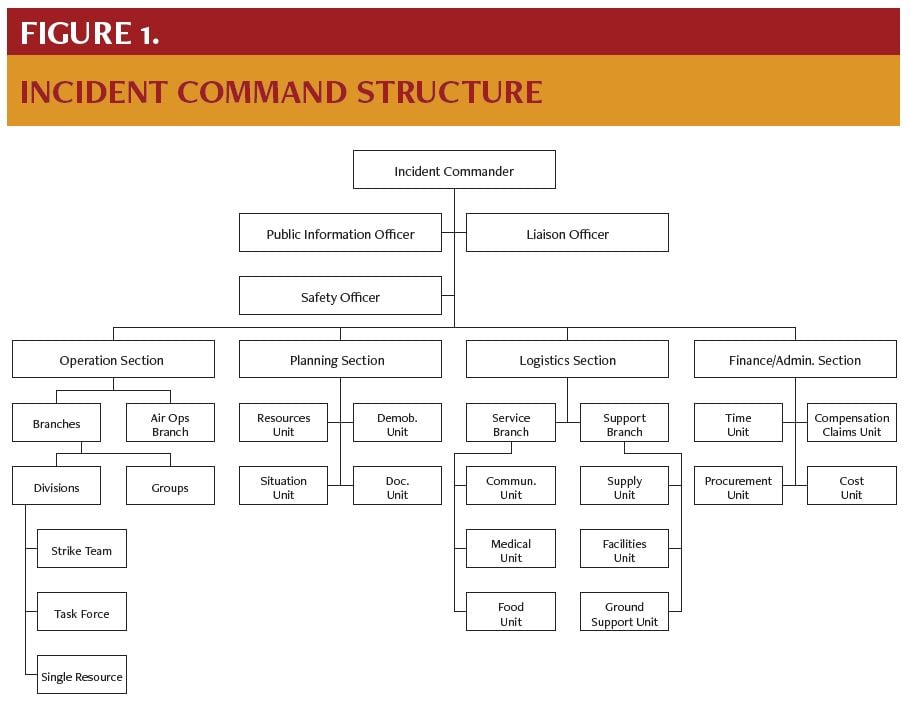

Incidents where resources are overwhelmed require many responders from many agencies. The management and integra- tion of all resources is critical for a good outcome. In the United States the incident command system (ICS) provides this frame- work.

ICS Structure

- Flexible virtual organization to meet the needs of time- limited situations

- Task-determined architecture linked by information pathways

- Modular design allows expansion or contraction to integrate needs and assets

- Goals (in order of priority): life safety, incident stabilization, and property conservation

- Directed by an incident commander to whom all responsibilities belong until delegated.

Main principles of ICS

- Unity of Command: Each person only answers to one superior.

- Span of Control: Each person has only 3-7 constituents immediately answering to him or her.

Residents

- Function under the operations section within the medical branch.

- Avoid freelancing; do not change roles unless instructed by superior.

References

- Lerner EB, Schwartz RB, Coule PL, et al. Mass casualty triage: An evaluation of the data and development of a proposed national guideline. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2 Suppl1:S25-34.

- Franaszek J. Medical care at mass gatherings. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(5):600-601.

- Mass Gathering Medical Care. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015;19(4)558.

- ICS Resource Center. FEMA Emergency Management Institute.