Ch. 2 - The Preclinical Years

If you have decided that EM is for you, then you are probably wondering what you can do to increase your chances of successfully matching. Your performance in preclinical courses and participation in extracurricular activities can impact your chances of matching at your top-choice residency program.1

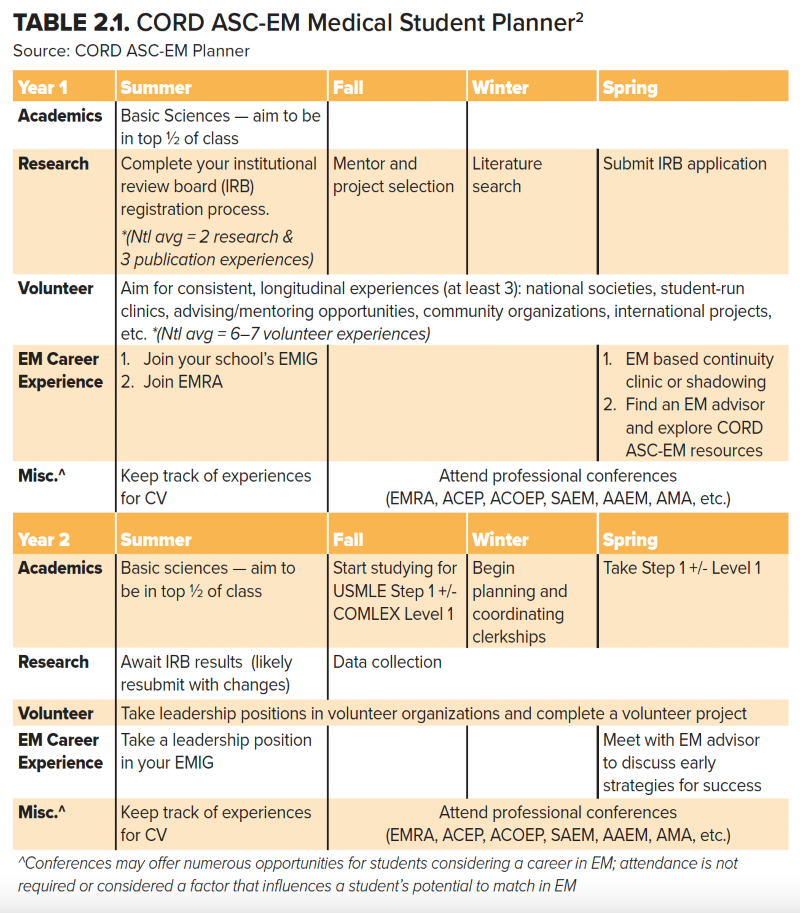

Start by reviewing Table 2.1, which was formatted using recommendations from the Emergency Medicine Medical Student Planner, as created by the CORD Advising Students Committee in EM (ASC-EM).2 Additional planners have been specifically tailored for applicant populations, such as osteopathic and military students. Those planners can also be found on the CORD ASC-EM website at www.cordem.org/resources/professional-development/ascem/. These planners are a great starting point and serve as a “map” through the EM application process by year of training. Please note that some planners were created before Step 1 became pass/fail, and the Step 2 average score may vary annually.

Academics: Preclinical Basic Sciences

Perhaps the most obvious component of the preclinical years is the basic science courses. Many schools are opting to grade courses as pass/fail, but regardless of the grading structure, you must have a firm grasp of the information. In EM, we are proud to see all types of patients and therefore are expected to manage and stabilize a wide range of maladies. Building a solid foundation will ideally prepare you for the USMLE Step 1 and/or the COMLEX Level 1 exams and the NBME/NBOME subject exams during your clinical years. Preparing for your success begins on Day 1.

At-Risk Candidates: Failing a course will be seen as a red flag, but failing one course does not automatically disqualify you from a residency in emergency medicine. What is most vital is identifying the reason for the failure and taking corrective action.

If you feel overwhelmed by the workload, reach out to the course director or someone in your school’s office of student affairs. Many students have been able to excel in undergraduate courses with mild learning disabilities, but, under pressure, might initially be unable to cope with the vast amount of work in medical school. Early recognition is important, and your school likely has resources to assist you. Further, there are many time-management resources online, ranging from videos to customizable planners and calendars.

Failing multiple preclinical courses is a more difficult hurdle to overcome. Often when a student fails multiple courses, they fall behind their original class. Failing two courses in the first year can possibly be remediated in the summer. However, failing two or more courses in the second year may delay the clinical years. If this happens, work with your office of student affairs, as staying in phase with your class will be weighed against your chances of scholastic success. If you are still considering EM, find an EM advisor ASAP. Failing multiple courses raises your risk of failing to match in EM — so be proactive.

It is worth noting a few other ways your preclinical performance will play a role in the residency application process. First, the Dean’s Letter, or Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE), includes information on your preclinical performance. The MSPE is a required component of the residency application and is reviewed by residency program leaders when deciding which students to invite for interviews. Second, preclinical performance is considered by school committees responsible for selecting honor society or fraternity members for induction into Alpha Omega Alpha or Sigma Sigma Phi.

Finding Advisors and Mentors

Finding advisors and mentors can be as difficult as it is to agree upon a definition of the two terms. During the preclinical years, many medical schools will assign advisors who might not be EM physicians. While their advice is important, their role is different from that of a specialty-specific advisor and mentor. The CORD ASC-EM defines advisors as EM academic faculty who provide specialty-specific, evidence-based advice.

In contrast, mentors will help coach you and often act as role models. They can provide guidance and can offer intelligent direction on more generalized career advice. Mentors should be individuals whose professional and personal advice you seek and whose character you hope to emulate in your own life.

A positive aspect of medical education is the shared support you’ll find from your professional community. Finding quality advising and mentorship will be beneficial, and multiple people can fill such roles. A mentor can be a peer who can offer their recent experiences to help guide you. If your school has an EM residency program, then shadowing a resident or faculty member can help establish a mentor-mentee relationship, or you can get matched to a mentor through the EMRA Student-Resident Mentorship Program.

Ideally, you should obtain an advisor who is designated by your school or EM department and is affiliated with an ACGME-accredited EM residency program. If such a person is not available, then start by contacting physicians in the ED and let them know you are seeking an EM advisor. While anyone who is residency-trained in EM can provide career guidance, a faculty member with expertise and experience in advising students through their preclinical and clinical years in preparation for a match in EM is best.

If your school does not have an affiliation with a core teaching hospital or a residency program, review the CORD ASC-EM advising resources at www.cordem.org/involved/Committees/advising-student-comm/. You may also benefit from the EMRA Student-Resident Mentorship Program.3 This online service allows students to connect with residents who self-identify as mentors. Students can also join virtual advising sessions through EMRA Hangouts.

Lastly, faculty advisors are often available during your EM elective or audition (out-of-town) rotations; consider asking the clerkship director or one of their residency leaders for an advisor.

Osteopathic Students: Your institution may not offer EM-specific academic advising if not affiliated with a residency program. If this is the case, consider reaching out to recent grads, local residency programs, and national mentoring programs through ACOEP-RSO, EMRA, or CORD.

Emergency Medicine Interest Groups (EMIGs)

A commitment to emergency medicine can be difficult to demonstrate during the preclinical years. One easy way is to join your school’s EMIG. By joining the group, you will gain insight into the world of emergency medicine. Skills workshops, ranging from suturing to advanced cardiac resuscitation, are often provided. Talks from local and regional experts are especially useful.

In addition to being a member of the EMIG, you can potentially become a leader of the organization. As a leader, you will be able to help shape and plan the workshops, and you will also gain other valuable leadership experience. Lastly, through your local EMIG, you will often meet seasoned advisors and mentors, and you may find more opportunities for research and/or clinical experiences.

Preclinical Exposure to EM

At many schools, EM is not a required rotation during your clinical years, so you may have limited exposure before the time you need to decide which specialty to pursue. Since it may be difficult to find extra time to shadow in the ED while on other clinical rotations as a third-year medical student, spending time in the ED early on can play a crucial role in helping you decide if this is the environment where you can see yourself spending the rest of your career.

Service, Leadership, and Advocacy

The NRMP Match data shows the mean number of volunteer experiences as 7.8 for allopathic students, 7.3 for osteopathic students, 5.2 for U.S. IMG students, and 6.0 for non-U.S. IMGs.1,4,5 While sporadic volunteer opportunities such as a day in a soup kitchen or working a support tent at a 10K are important, long-term involvement with a program is viewed as more substantive.

Program directors (PDs) in EM were surveyed by the NRMP, and 70.3% reported that leadership qualities were an important factor in determining competitiveness for residency. This was noted to be more important than your personal statement and honor society membership.6

While EMIGs are a great way to get your “feet wet” with leadership roles, additional options to get involved are through local, state, and national EM organizations such as EMRA and ACEP. By getting involved at the state or national level, you can advocate for the interests of your patients and colleagues and develop the skills to become a leader. These are also great opportunities to meet other students, residents, and faculty who are excited about EM. While leadership and extracurricular activities may help enhance your residency application, remember that mastering the basic sciences and building strong foundational knowledge should always come first.

Research as a Medical Student

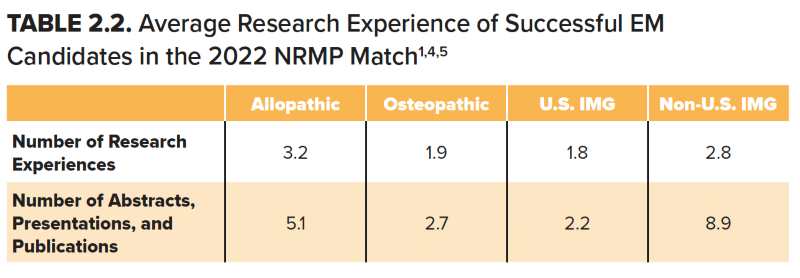

Program directors use many criteria to help select their residency class. The number of research experiences by various applicant groups varies (Table 2.2).1,4,5 Though this amount of research involvement may seem intimidating during medical school, many medical students have performed research before medical school. The residency application often includes all research performed, including research done during undergraduate and graduate education. Fortunately, the PD survey demonstrates that only 36.5% of PDs report research was important for offering interviews, and only 23% said it was important for ranking.6

While performing research can be beneficial, finding the “perfect” research project during medical school can be difficult. Doing research just for the sake of doing research is often not advised, especially given the lower emphasis EM PDs place on this activity. Furthermore, doing research to pad your CV or to have another talking point during your residency interviews is also not advised. It is usually clear during the interview process how much involvement one had in the projects they have listed and whether they were truly passionate about the work.

If your school does not have a department or division of EM, finding a project that interests you outside of EM is an option. Most medical schools have contacts for research opportunities. If your medical school does not, reach out to faculty in EM to see if there are any research projects for you to join. Lastly, your medical school may be close to another, and perhaps you can find a research project advisor or mentor at that location.

Initial Medical Licensing Exam

Finding leadership and research opportunities in medical school will provide valuable experiences, contribute to a robust EM application, and ultimately contribute to your effectiveness as an emergency physician. However, no amount of leadership, research, or volunteer activities can compensate for a medical licensing exam failure.

In 2022, both the USMLE Step 1 and COMLEX Level 1 changed to a pass/fail scoring system.7 Both exams were previously reported as a pass or fail grade, as well as a score. This scoring metric was used by PDs to evaluate and compare residency candidates.

There are multiple reasons why it is important to study and do your best on Step 1/Level 1. Passing on the initial attempt is very important. On the 2021 NRMP PD Survey, PDs rated the mean importance of certain performance characteristics in deciding whom to interview: failed USMLE or COMLEX exams had the highest mean importance rating of 4.6 and 4.7 out of 5, respectively.6 Failing a USMLE or COMLEX exam is a red flag and will significantly impact your likelihood of matching in EM. Additionally, performance on USMLE Step 1 has a strong positive correlation with performance on Step 2, which produces a test result (pass/fail) and a test score (three-digit score range of 1 to 300).8

Because passing Step 1/Level 1 on your first attempt is highly important to EM PDs, you should plan early on how to best prepare for the exam(s). First, talk with your mentors, especially if they are residents or students more senior to you. You may find it beneficial to purchase commercially available review books, flashcards, and question banks as study aids during your preclinical years to maintain basic science knowledge through Step 1/Level 1. Recent research suggests that first-year medical school performance and retrieval practice in the form of practice questions are effective ways to prepare for the USMLE Step 1.9 While passing your classes needs to be your top priority, studying the relevant board review material simultaneously is a great way to prepare for Step 1/Level 1 and subsequently Step 2.

Osteopathic Students: Though osteopathic medical schools require COMLEX Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3 for licensure, many residency programs require USMLE Step 1 and/or 2 for all applicants. Use EMRA Match to filter programs based on licensing examination performance and if USMLE is a requirement.

There are also differences in the programs that accept COMLEX alone compared to those that still prefer USMLE. For example, in one recent study, the primary training site of programs that accept COMLEX alone are more commonly community-based than university-based.10 While some programs filter applications in ERAS based on licensing exam scores available, not all do.11 In November 2018, the AMA House of Delegates created a policy calling for the AMA to promote equal acceptance of USMLE and COMLEX scores.12 The study outlined above found 107 programs (of the active 278 programs at the time) preferred USMLE scores, while 151 reported accepting COMLEX scores alone.10

Additionally, acceptance of COMLEX Level 1 may change with USMLE Step 1 and COMLEX Level 1 now being pass/fail examinations, but that is still unknown. Available data indicates that if you are an osteopathic medical student, taking at least USMLE Step 2, in addition to COMLEX Level 2, will open more opportunities for residency interviews.

At-Risk Candidates: While most students take and pass USMLE Step 1/COMLEX Level 1, some do not. Not passing Step 1 of the licensing examination will significantly impact your application strategy. However, an unpublished survey by CORD ASC-EM indicates there are programs willing to consider applicants who retake Step 1 and pass.13 If you fail Step 1, contact your office of student affairs and your advisor so you can come up with a plan to retake the exam and perform well. Students can use EMRA Match to filter which programs report having recently interviewed applicants who have previously failed Step 1 for a below-average score by taking Step 2 early and ensuring strong performance on clinical rotations.

As you look forward to the clinical years of medical school, remember the best students and physicians built strong foundational medical knowledge during the preclinical years of medical school. The effort you put forth during your first two years will pay dividends for you and your patients as you move into your clinical rotations, residency, and beyond.

The Bottom Line

- The preclinical years provide a crucial foundation for the knowledge needed to succeed on medical licensing exams, during your clinical years, and on your EM rotations. Effort in the early years has a huge return on investment for the residency application process.

- Seek out opportunities to explore EM early; this will help you decide if EM is a good fit for you.

- If you have a red flag such as a Step 1 or Level 1 failure or a failed preclinical course, seeking early guidance from an EM advisor is critical.

- When planning your research and volunteer activities, keep in mind that PDs value meaningful commitment over sporadic and superficial involvement (quality over quantity), and choose to dedicate your time to activities you truly care about.

References

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting Outcomes in the Match: Senior Students of U.S. MD Medical Schools. July 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Charting-Outcomes-MD-Seniors-2022_Final.pdf.

- CORD Advising Students Committee for Emergency Medicine. Emergency Medicine Medical Student Planner. 2018. https://www.cordem.org/globalassets/files/committees/student-advising/_2018-satf-general-medical-student-planner.docx.pdf?usp=sharing.

- Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association. Student-Resident Mentorship Program. https://www.emra.org/students/advising-resources/student-resident-mentorship-program/.

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting Outcomes in the Match: Senior Students of U.S. DO Medical Schools, July 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Charting-Outcomes-DO-Seniors-2022_Final.pdf.

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting Outcomes in the Match: International Medical Graduates, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Charting-Outcomes-IMG-2022_Final.pdf.

- National Resident Matching Program Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2021 NRMP Program Director Survey. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf.

- Step 1 Common Questions. USMLE. https://www.usmle.org/common-questions/step-1.

- Jacobparayil A, Ali H, Pomeroy B, et al. Predictors of Performance on the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 2 Clinical Knowledge: A Systematic Literature Review. 2022;14(2):e22280.

- Giordano C, Hutchinson D, Peppler R. A Predictive Model for USMLE Step 1 Scores. Cureus. 2016;8(9):e769.

- Nikolla D A, Jaqua B M, Tuggle T, et al. Differences Between Emergency Medicine Residency Programs That Accept the Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination of the United States and Those That Prefer or Only Accept the United States Medical Licensing Examination. 2022;14(2): e22704.

- Negaard M, Assimacopoulos E, Harland K, Van Heukelom J. Emergency Medicine Residency Selection Criteria: An Update and Comparison. AEM Educ Train. 2018;2(2):146-153.

- Murphy B. DO and MD Licensing Exams Should Be Viewed Equally, Says AMA. American Medical Association, 14 Nov. 2018, ama-assn.org/residents-students/match/do-and-md-licensing-exams-should-be-viewed-equally-says-ama.

- Pelletier-Bui AE, Schrepel C, Smith L, et al. Advising special population emergency medicine residency applicants: a survey of emergency medicine advisors and residency program leadership. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):495.