Ch. 14. Corporate Practice of Medicine Corporations Are People Too?

Nicholas S. Imperato; Aaron R. Kuzel, DO, MBA; Angela G. Cai, MD, MBA

Chapter 14. Corporate Practice of Medicine

Recorded by Aaron Kuzel, DO, MBA | University of Louisville

Laws regarding the Corporate Practice of Medicine describe a doctrine that places limitations on the practice of medicine to licensed physicians. Such laws prohibit corporations from practicing medicine, directly employing a physician, or influencing the medical decision-making of a physician in their practice. The majority of states within the United States have laws prohibiting the corporate practice of medicine, but limitations as to the practice vary state to state. These prohibitions seek to protect and preserve the practice of medicine as well as discourage the profit-generating mentality of corporate business practices or the “commercialization” of care.1

The concern with corporate actors in medicine is the conflict of interest between financial performance vs. the patient care, educational, and research missions of EM practice and training.

Within the specialty of emergency medicine, the Corporate Practice of Medicine has been an issue of debate, as a rising number of corporate-backed medical groups employ emergency physicians across the specialty. At the time of publication, the American Academy of Emergency Medicine Physician Group (AAEM-PG) has filed a lawsuit against Envision Healthcare with accusations of illegal corporate practices of medicine in the Superior Court of California.2 The lawsuit has been supported by an amicus brief by ACEP and a declaration of support by EMRA. The topic is complex and affects much of the life and practice of emergency physicians – and it continues to be an area of debate within the specialty. With such practices, there are certain concerns such as a corporation’s political and business alignment. Will the corporation first prioritize their alignment with their shareholders or to their patient? Will physicians continue to have autonomy over their medical decision-making, or will this decision-making be altered to maximize profits?

The Corporate Practice of Medicine Laws

The corporate practice of medicine (CPOM) is a legal doctrine that prohibits companies from practicing medicine or directly employing a physician to provide medical services.3 These laws uphold ethical standards that separate medical judgment from the influence of profit incentives by corporate or private entities. Most states have laws prohibiting the corporate practice of medicine, however, almost every state provides broad exceptions to the doctrine. All states with laws on the corporate practice of medicine allow for professional corporations or associations to provide medical services if wholly owned by physicians.3 Additionally, hospitals and hospital systems also receive exemptions to employ physicians to provide medical services, although there are also laws prohibiting the hospital employer from interfering with the physician’s independent medical judgment.4,5 Texas state law has strict protections for independent physician medical judgment so that a physician cannot be disciplined for reasonably advocating for patient care.6

Since these laws have been enacted, they have been regularly shaped by legislation, federal and state regulation, as well as decisions from higher courts and state’s attorney generals. Many of the specific regulations vary between the states, but in general, the states mandate that all or the majority of shareholders of a medical corporation must be physicians licensed within the state of the medical practice.3 Each state allows for the formation of professional corporations with the specific purpose of these corporations to provide a professional service. How these corporations operate and render their services varies from state to state. In Arkansas, for example, the board of directors and shareholders of a physician group must be physicians licensed in Arkansas.7 In contrast, the Colorado statutes allow for a physician assistant to be a shareholder of a corporation, provided physician shareholders maintain majority ownership in the corporation.8 Corporate practice of medicine laws are often shaped not only by legislative and regulatory bodies but also by boards of medical licensure. Often boards of medical licensure will offer exceptions to the doctrine as it pertains to the employment of physicians, as long as the physician maintains autonomy in decision-making.

Why It Matters to EM and ME

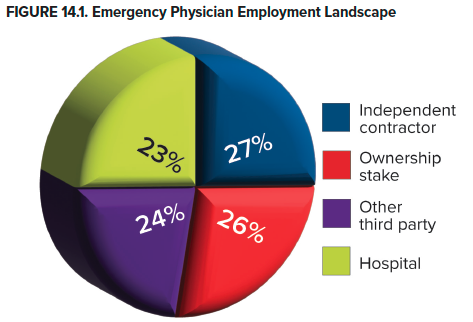

Understanding the corporate practice of medicine doctrine is critical for emergency physicians as this intersects with the employment and practice of the emergency physician. Physicians in all specialties are now more likely to be employees rather than owners of their own practices. Prior to 2018, the majority of physicians owned their own practice, but now 45.9% of physicians have ownership stakes in their practices, whereas 47.4% are employed. Emergency medicine has the lowest proportion of physicians who have an ownership stake in their practice (26.2%). Further, emergency medicine has the highest percentage of physicians who work as independent contractors (27.3%) and the highest proportion of physicians directly employed with a hospital (23.3%).9

One of the greatest concerns from emergency physicians as it relates to the corporatization of medicine is the loss of physician autonomy and the conflict of interest that sometimes exists between profit generation and patient care best practices. During a 2022 Federal Trade Commission Listening Session with ACEP President Dr. Gillian Schmitz, she shared the results of a questionnaire to ACEP members that found that greater than half of those emergency physicians affected by corporate mergers of acquisition experienced a negative impact to their medical decision-making autonomy. This interference can significantly impact quality of care and patient safety.10,11 Leaders within emergency medicine raise concerns that as corporations seek to maximize profits, there will be drastic reductions in physician autonomy, quality care, and patient safety.12

The staffing structure of emergency physicians through physician practice management groups with corporate structures (discussed below) has led to concerns about lack of due process protections.10 The right to due process is well-established in health care through the Healthcare Quality Improvement Act of 1986 and affirmed by the Joint Commission via the Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals, and the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.13 Emergency physicians, who are frequently employed through staffing groups, often do not have access to due process protections guaranteed to physicians directly employed by the hospital; many are asked to waive due process rights as a condition of their employment contract.14

How We Got to This Point

CPOM has shaped the United States health care system and will continue to mold it for years to come. In the late 19th century, mining, lumber, and railway corporations began to expand significantly, leading many of them to employ physicians to provide care directly to their employees. While these companies employed physicians to provide medical services, other companies decided to contract with physicians in exchange for a portion of all medical fees that were charged. These companies would also help market the physician’s services to the public. As these companies’ interest in physician services grew, decision-making began to move out of the physicians’ hands and into those of laypeople.15

The CPOM doctrine arose in the early 1900s, essentially as a way to prevent corporations from practicing medicine or employing physicians, with an overarching goal of “preserving the sanctity of an independent physician-patient relationship.”16 This general principle prohibits the practice of medicine by an unlicensed individual and prevents corporations from practicing medicine. There was fear that it was unlikely that the motives or interests of physicians would align with the potential profit-centered mentality of corporations. This doctrine was built on the premise of three main policy concerns:3

- Corporations either employing physicians or practicing medicine would lead to the overarching corporatization of medicine.

- If physicians were employed by corporations, then they may be unable to provide unbiased, independent medical decisions.

- There may be a distinct opposition between shareholders' desires and physicians' or patients' interests.

Despite those policy concerns, the health care system continued to evolve and consolidate, and the Mayo Clinic became a model for bringing specialists together into larger group practices. These large groups of physicians began the model of prepaid group plans. Eventually, these prepaid group plans began to enroll employee groups, offering capitation fee-treatment arrangements. One of the first plans was the Group Health Association of Washington, with later similar groups such as the HIP Health Plan of New York or Kaiser-Permanente. These consolidated practices and the employment of physicians by corporations laid the groundwork for the further corporatization of emergency medicine.15

The corporatization of emergency medicine and the health care system, in general, is directly related to the rise of managed care organizations (MCOs). In 1973, under the Nixon Administration, the Health Maintenance Organization Act (HMO) was passed. Through this piece of legislation, federal funds were made available to help develop HMOs throughout the nation. Similar to the prepaid groups discussed previously, the belief behind HMOs was that capitated, prepaid medical care would provide an effective and less expensive alternative to the fee-for-service model. MCOs are large organizations, often indistinguishable from corporations or health insurance organizations, that integrate financing, insuring, and delivering care while controlling the utilization of services. In an effort to reduce costs, we have moved towards a significantly more corporatized system.15

Physician groups have also corporatized by forming physician practice management (PPMs) or contract management groups. These groups initially started as physician-owned staffing agencies that helped ensure that well-trained physicians consistently staffed emergency departments. In early 1961, Dr. James Mills Jr., a physician in Virginia, became one of the first to develop and utilize the present-day ED structure. Emergency patients at his Alexandria Hospital were charged $5 per visit, and the ED was covered by physicians working various shifts throughout the day. Around the country, hospitals dealt with the increased patient volume by contracting full-time physicians to staff their EDs. To increase efficiency in staffing, PPMs were then developed. As many of these groups began to expand and emergency medicine became a profitable business, outside investors such as private equity and public stock shareholders have become investors or owners in these businesses.17

PPM structures raise questions about appropriate levels of overhead. All physician practices have backend expenses or overhead that must be accounted for in the practice and these expenses offset the revenue an individual physician receives. These expenses can include malpractice insurance premiums, coding and billing costs (including compliance, audit appeals and collections), physician management services including medical director salaries, physician recruiting and onboarding costs, personnel and payroll expenses, and other group administrative expenses.18 How these expenses are paid varies with each group and can range from direct billing of expenses to a management services company or backend percentage-based fee. The concern with these overhead fees in any practice not controlled exclusively by physicians, including PPMs, is that the administrative arm can increase the fee beyond the actual expenses of the group to generate profit. Where the administrative arm has the power to set fees and collect them without regard to the expense, there is the potential for abuse and ethical concerns.

Current State of the Issue

Emergency Medicine Practice Models

The nature of emergency medicine does not lend itself to solo physician practices. Emergency physicians can be employed by hospitals, academic institutions, physician practice management groups (which may be physician-owned or corporate-owned), federal entities (such as the U.S. Armed Forces, Veterans Affairs, Indian Health Services, or the CDC) or as independent contractors.

Hospitals and Academic Practices

Emergency physicians can be directly employed by a hospital or academic medical center. Employees of hospitals and academic groups often enjoy guaranteed salaries and benefits and avoid the administrative burdens of running a private practice. Nonprofit hospitals and health systems are classified by the Internal Revenue Service as charities and, as such, are not obligated to pay federal income or state and local property taxes. For-profit hospitals are owned either by investors or shareholders of a publicly traded company.19

For-profit hospitals can have a wide range of owners, including physicians, individual investors, publicly traded groups, private equity firms, or some combination of these owners. Per the 2021 MedPAC report “Private Equity in Medicare”, in 2020, 4% of hospitals, or 115 hospitals, were owned by private equity firms, and 22% of hospitals were owned by other for-profit entities such as publicly traded corporations and physician practices, while the remaining 74% of hospitals were nonprofit or government-owned facilities.20 One of the largest examples of private ownership of a health care system is the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA Healthcare), which owns 184 hospitals. HCA Healthcare represents 20% of all for-profit hospitals and has shifted ownership numerous times between private and public ownership, including a period of private equity ownership.20

One particularly controversial private equity acquisition occurred in 2018 with the purchase of Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia by a private equity firm, followed by the firm quickly closing the hospital a year later – effectively removing a safety net from a vulnerable population center21 and disrupting the education of hundreds of residents.22 However, given the dire financial situation of the hospital, it is unclear whether the hospital would have remained open if publicly traded or physician-owned.20

Physician Group Practices

Emergency physicians can join a spectrum of group practices, or PPMs, which maintain staffing contracts with emergency departments and hospitals. PPMs range in size from a small group of physicians covering one emergency department to group practices that cover multiple hospitals within a region or nationally.

Differentiating Features

There are many features that differentiate various EM group practices, including democratic governance, billing and financial transparency, independent contractor status, and ownership (physician vs non-physician). In democratic groups, the physicians practicing in the group are offered the opportunity to become partners or owners of the group, usually after a certain period of employment with the group. Benefits and privileges of partnership range from completely flat structures to tiered based on level of partnership. The structure of the democratic governance can vary in many ways including: who makes decisions to accept new partners, the track to partnership, the vesting period, the cost of the financial buy-in, which aspects of the company a partner owns, profit-sharing, voting power, and the scheduling preferences granted towards partners and non-partners.23 Democratic groups vary in size, but tend to be local or regional employing <100 physicians with annual volumes <250,000 patients.24

Groups and employers vary in their transparency of billing and financial statements. The most transparent groups provide regular reports of what the group has billed under the physician’s name and how much the group retains for administrative overhead.25 Employment contracts for emergency physicians with a group or health system are defined by one of two tax statutes: 1099 (as an independent contractor) or W2 (employee). W2 employees often enjoy more benefits than their 1099 contractor counterparts (such as health insurance and retirement benefits), whereas 1099 contractors typically receive higher salaries. 1099 employees are responsible for their own employment taxes; however, they are allowed significant additional tax deductions for business expenses.26

Financial control and ownership of groups can vary widely, often including combinations of physicians or corporate entities, which generally refers to private equity, venture capital, insurance companies, or public shareholders.27

Corporate Investors and Owners

What is Private Equity?

Private equity (PE) is a broad term to describe activities where investors purchase an ownership stake in companies or financial assets not publicly traded on public stock exchanges.28

The private equity investment life cycle begins when a PE firm starts raising money from outside investors.20 These investments are pooled into an investment fund that operates for a specific period of time; often around 10 years.29 The PE firm then buys and sells companies with the goal of improving their performance to increase their value, and then selling them a few years later, within the life of the fund, at a profit.20 When acquiring companies, PE firms often borrow money to make the purchase in a process called a leveraged buyout.30 Borrowed money is preferable to these firms, as the borrowed money can increase the potential return on investment as private equity firms can use less of its own capital to acquire companies thereby generating profit on a larger company with a smaller investment, and also provides a tax incentive as the borrowed money reduces a company’s tax liability. This is one of the controversial features of private equity investments as the debts taken on by PE firms are owned by the newly purchased company and not the PE firm, thus if the company eventual files for bankruptcy, the PE firm is not responsible for that debt.29 Private equity returns can be an attractive investment as their returns are often similar to returns from mutual funds that invest in smaller companies.31

Private Equity in Health Care

Private equity investments and buyouts have been present in health care since the 1980s but have been more noticeable over the past two decades. A private equity research firm estimated in 2019 that buyouts from private equity firms involving North American health care workers totaled $46.7 billion, which was an increase of $28.6 billion from 2018. In 2019, private equity buyouts accounted for 60% of all health care-related buyout transactions.32 In a Medicare Advisory Committee Report to Congress, the report detailed the number of private equity funds investments in health care to include retail health, behavioral health and substance abuse centers, hospice centers, and physician practice management groups in specialties such as dermatology, radiology, gastroenterology, and ophthalmology.20 Health care and health care facilities have become a recent priority for private equity in the United States given the demand for services related to an aging population and extended period of low interest rates prior to the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, health care was an attractive investment for private equity given the stable, growing demand of health care in the United States, the use of insurance and fee-for-service payments, which meant predictable cash flow.20

Private equity is pervasive within health care, even among systems that most physicians and patients believe to be reputable. According to Modern Healthcare’s Annual Health Systems Financial Database, the 5 health systems with the largest private equity investments in 2020 were the Kaiser Foundation, Mayo Clinic, Ascension, Cleveland Clinic, and Advocate Aurora Health, with Mass General Brigham being a close sixth. These health systems are all registered as a 501(c)(3) organization and are considered not-for-profit.33

Hospitals

Overall, PE firms seek to generate profits by implementing processes that increase revenues (such as serving more privately insured patients, providing more services especially well-compensated procedures) while decreasing costs (such as taking advantage of economics of scale and reducing labor costs by reducing staffing and decreasing employee compensation, including substituting less expensive clinicians for more expensive clinicians). A cross-sectional analysis performed by the 2021 Medicare Advisory Committee Report to Congress found that private equity-owned hospitals tended to have slightly lower costs and lower patient satisfaction scores than other hospitals. MedPAC did not find any statistically significant difference in patient mortality or other quality metrics, but the data on the impact of PE on quality of care is very limited.20

Physician Practices

Physician practices are a prime target for private equity investment, as most physicians have historically worked in small practices, creating a market that is fragmented rather than consolidated; 56% of non-government employed physicians are in a practice of 10 or fewer physicians, making these practices excellent targets for private equity buyouts.34 While the share of physicians in mid-size practices (11 to 49 physicians) has remained stable, there has been a surge in group practices of 50+ physicians due to increasing integration of physician practices with health systems. Between 2016 and 2018, the number of physicians affiliated with health systems in the United States grew from 40% to 51%; as a result, the private equity firms and health systems are competing for purchases of physician practices thus increasing the pace of physician practice consolidation.35

The latest data in EM suggests that private equity-backed physician employers staff 25% of U.S. emergency departments.36 However, estimating the total number of physician practices fully or partially owned by private equity firms is difficult as many of these transactions are not publicized or protected by nondisclosure agreements.26 One study found that 355 practices were acquired by private equity firms between 2013 and 206, accounting for 2% of the ~18,000 practices in the United States, but this number does not account for any practices acquired by PE firms before 2013 or after 2016.37 Specialty practices most commonly consolidated into private equity investments are family practice, emergency medicine, anesthesiology, and dermatology. Even in the setting of the pandemic, private equity interest in acquiring physician practices has remained high, and this form of corporate investment in medicine will continue to be an issue for the future of EM.38

Moving Forward

Cause for Concern

Corporate involvement in medical care can create a conflict of interest between financial performance and all the other responsibilities of our health care system, including the patient care, educational, and research missions of EM practice and training.39 While all health care businesses must generate profit, certain corporate structures may incentivize business decisions at odds with physician and patient well-being. For example, the economics of private equity control might incentivize riskier, more aggressive strategies that are especially concerning given the lack of transparency in health care relative to other industries where private equity invests.19 While objective data on the impact of private equity or other corporate investors in EM is lacking, more data is available in the nursing home industry. The role of PE in creating poor patient outcomes alongside increased costs to patients and the government in the nursing home industry has led the public and Congress to scrutinize their presence in health care overall.20,40 More data and more transparency are both needed in order to better understand the impact of corporate investment on patients and physicians in emergency medicine.

TAKEAWAYS

- When choosing a place of employment, consider the benefits and risks of each type of practice in emergency medicine. Advocate for places of employment that value the protection of physician autonomy and preserve due process rights.

- Educate yourself about the changing practice landscape for emergency physician employment, use this knowledge to determine which employment arrangement will work best for your career.

- The corporate practice of medicine varies from state to state. Know what safeguards are provided from your local and state legislatures in order to protect your autonomous decision-making.

References

- Silverman SI. In an Era of Healthcare Delivery Reforms, The Corporate Practice of Medicine is a Matter that Requires Vigilance. Health Law & Policy. 2015; 9(1):1-23

- AAEM. AAEM-PG files suit against Envision Healthcare alleging the illegal corporate practice of Medicine. AAEM Physician Group. Published December 21, 2021.

- American Medical Association. Issue brief: corporate practice of medicine. Advocacy Resource Center. 2015.

- 42 U.S.C. Section 300e-10(a)

- Elizabeth Snelson, Physician Employment and Alternative Practice Strategies: Avoiding “Company Doctor” Syndrome and other Hospital Medical Staff Issues, 21 Health Law. 14 (2008).

- TEX. HEALTH AND SAFETY CODE ANN. § 311.083(g) (2011)

- ARK. CODE ANN. §4-29-307(a)

- COLO. REV. STAT. §12-36-134(1)(d)

- Kane CK. Updated data on physician practice arrangements: For the first time, fewer physicians are owners than employees. Chicago, IL. American Medical Association; 2019. Policy Research Perspectives.

- ACEP. Impacted by EM consolidation? tell the federal government. Published March 24, 2022.

- Stone W. An ER doctor lost his job after criticizing his hospital on covid-19. now he's suing. NPR. Published May 29, 2020.

- Stacey K. US doctors fear patients at risk as cost cuts follow private equity deals. Financial Times. Published November 11, 2021.

- EMRA. Physician Due Process Rights. Published June 11, 2018.

- ACEP. Guaranteeing Emergency Physician Due Process Rights.

- Shi L, Singh DA. Delivering Health Care in America: A Systems Approach. 8th edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2021.

- Mars SD. The Corporate Practice of Medicine: a Call for action. Health Matrix: The Journal of Law-Medicine. 1997;7(1):241.

- Derlet RW, McNamara RM, Plantz SH, Organ MK, Richards JR. Corporate and Hospital Profiteering in Emergency Medicine: Problems of the Past, Present, and Future. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(6):902-909.

- ACEP. Emergency Physician Practice Costs. Approved June 1987; revised 1992;1997;2002;2009;2016;2022. Available at https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/emergency-physician-practice-costs/.

- GWU. Profit vs. Nonprofit Hospital administration: GW University. Published July 15, 2021.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. 2021. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

- Pomorski C. The death of Hahnemann Hospital. The New Yorker. June 7, 2021.

- Redford G. What happens when a teaching hospital closes? AAMC News. July 12, 2019.

- ACEP Democratic Group Practice Section. Before you sign on: Caveat emptor.

- ACEP Democratic Group Practice Section. 2019 Democratic Group Praction Section Survey. Published 2019.

- ACEP. Your Rights to Medicare Billing Information.

- Nitti T. IRS publishes final guidance on the 20% pass-through deduction: Putting it all together. Forbes. Published April 14, 2022.

- American Medical Association. Issue brief: Corporate investors. Chicago, IL: AMA. Published 2019.

- Cendrowski H, Martin JP, Petro LW, Wadecki AA. Private Equity: History, Governance, and Operations. Somerset: Wiley; 2011.

- Mercer. Understanding private equity: A primer. Published 2015.

- Morran C, Petty D. What private equity firms are and how they operate. Propublica. Aug. 3, 2022.

- Altegris Advisors. There is no new normal in the world of private equity. La Jolla, CA: Altegris Advisors. Published 2021.

- Bain & Company. 2020a. Global healthcare private equity and corporate M&A report 2020. Boston, MA: Bain & Company.

- Modern Healthcare. By the numbers: Health Systems with largest private equity investments, 2020. Modern Healthcare. Published May 9, 2020.

- Kane C. 2019. Updated data on physician practice arrangements: For the first time, fewer physicians are owners rather than employees. Chicago, IL: AMA.

- Furukawa MF, Kimmey L, Jones DJ, et al. Consolidation of providers into health systems increased substantially, 2016-18. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1321-1325.

- Wolfson BJ. ER doctors call private equity staffing practices illegal and seek to ban them. Kaiser Health News. Dec. 22, 2022.

- Zhu JM, Hua LM, Polsky D. 2020. Private equity acquisitions of physician medical groups across specialties, 2013–2016. JAMA. 2020;323(7):663-665.

- Bruch J, Gondi S, Song Z. COVID-19 and private equity investment in health care delivery. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(3):e210182.

- EMRA. Unity, Purpose, and Passion: Influencing the Future of the EM Workforce. Published Jan. 31, 2022.

- Knight V. Private equity ownership of nursing homes triggers Capitol Hill questions – and a GAO probe. Kaiser Health News. April 13, 2022.