Ch. 5. Physician Payment 101

Nishad Abdul Rahman, MD; Nicholas Rizer, MD; Jordan Celeste, MD, FACEP

Chapter 5. Physician Payment 101

Recorded by Jacob Altholz, MD | UNLV/Nellis Air Force Base

Physicians generate revenue and earn income based on several encounter-specific factors, including acuity, risk of the presenting condition, the work-up ordered by the physician, and, prior to 2023, the comprehensiveness of charting. Physician productivity and subsequent financial compensation is measured in units of productivity known as relative value units, (RVUs), which are influenced by the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RVS) Update Committee, called the RUC (referred to as “the Ruck” colloquially.)

Changes to physician payment structure will continue over the years to come. Physicians must be at the forefront, ensuring that we create the appropriate financial incentives that will drive a positive future for emergency medicine while minimizing unintended consequences.

Why It Matters to EM and ME

As physicians, we measure our own success on a scale of lives saved and morbidity prevented. Unfortunately, this is not how productivity is calculated by payers for health care services or employers determining physician compensation. To them, it all comes down to dollars and cents, and physician productivity must be calculated using metrics. Physician employers most often delineate financial compensation at least in part based upon RVUs generated, regardless of whether you work for a hospital, a small democratic group, a privately owned company, or a large contract management group. It is critical that every physician understands RVUs to ensure their clinical practice remains economically viable and to establish their own financial well-being.

How We Got to This Point

The history of physician payments long predates the development of emergency medicine as a specialty. The dominant model of physician payment in the early 20th century relied on direct payments by patients to doctors for the work performed by the doctor.1 This would form the basis of the fee-for-service model, where separate fees were paid to the physician for each and every service provided. The physician would charge the patient a bill and the patient would pay to the best of their ability. This model came under increasing scrutiny in the 1910s, when calls for widespread health insurance began to grow. In 1915, the American Association for Labor Legislation (AALL) introduced a compulsory medical insurance draft bill in multiple state legislatures. Initially, the American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates expressed support, but by 1920, the AMA was against the measure.2

Then, after the stock market crash in 1929, the Great Depression strained industries including the health care sector. Like most organizations in the country, Baylor University Hospital was under tremendous financial stress, with lower payments per patient and fewer patients coming to the hospital.3 The hospital’s administrator decided to counter the lost revenue by securing a steady income stream. In 1929, 1,250 Dallas public school teachers contracted with Baylor University Hospital for 50 cents per month, which secured them up to 21 days of hospitalization per year. The concept of prepaid hospital plans expanded across the country, providing a cash flow that helped keep the hospitals afloat during these lean years and provided security from calamity for customers. These plans were the precursors to today’s Blue Cross.

As Blue Cross plans spread, the American Hospital Association stepped in to set guidelines designed to reduce price competition among hospitals. Instead of locking patients into only one hospital, like the 1929 Baylor Plan, open access to multiple hospitals became recommended.

However, Blue Cross plans accounted only for hospital insurance, specifically excluding physician fees, and the AMA continued to oppose compulsory health insurance. The AMA and its members were wary of health insurance during the 1930s, fearing potential for the loss of professional autonomy. This began to change in 1939 as the AMA started encouraging state and local medical societies to offer pre-paid medical insurance plans to cover physician services. Their acceptance was multifactorial: Blue Cross wanted to secure physician services in order to compete with other commercial insurers and offer comprehensive coverage beyond only hospital care, while the AMA wanted to head off potential far-reaching government reform proposals by establishing voluntary insurance options. The physician-organized plans covering physician services would eventually affiliate together and become Blue Shield.2,3,4

Regulations during World War II accelerated the adoption of employer-sponsored health insurance plans, including Blue Cross and Blue Shield. As part of the war effort, wage increases were limited to ensure a stable labor force for war manufacturing. While wage negotiations were limited, the federal government did allow employers to offer benefits such as health insurance, which firms used to differentiate themselves and attract workers. While these war-time regulations helped spur the adoption of employer-sponsored health insurance plans, tax regulations rapidly accelerated their development. In 1954, the Internal Revenue Service ruled that employer contributions to employee health insurance were not part of regular income and hence not taxable. This was a boon for both employers, who could now offer untaxed (and hence essentially subsidized) benefits to attract workers, and health insurers.5

The fee-for-service model arose from these early insurers, who would reimburse patients for hospital and physician bills.6 Medicare and Medicaid built upon the existing chassis of the private fee-for-service structure, with the government paying physicians their usual and customary rates, instead of private third-party insurance companies.7,8

Initially administered separately by individual agencies, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) was established in 1977 to coordinate both Medicare and Medicaid.9 In 2001, as part of efforts to improve and reform the original institution, HCFA was renamed the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), as it is known today, and charged with three separate goals: first, to ensure Medicare beneficiaries know all of their potential choices including HMOs; second, to administer traditional Medicare; and third, to work with state-administered programs such as Medicaid and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program.10 By the 1980s, concerns regarding the cost of physician payments under the “usual, customary, and reasonable” charge schema developed. Due to concerns over rising health care costs, overvaluing procedures, and misaligned incentives, policymakers sought to develop a more rational payment system. Congress authorized a study by the AMA and Harvard University to determine the "relative value" of physician services compared to one another, a system that would become known as the resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS).11 The 1992 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act established the RVU, with each physician service assigned a number of RVUs, the basis for Medicare payments to physicians. This has remained the basis for physician payments, whether to physicians themselves or the organizations that employ them, for the overwhelming majority of physicians nationwide, including emergency physicians.12 The impact of RVUs goes beyond just Medicare patients, as private insurance companies typically base their physician payments on CMS payments.

Current State of the Issue

In practice, how do RVUs work? Every physician encounter and procedure is given a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) code. CPT codes are standardized codes that encompass the full range of medical services and procedures developed by the AMA, which allow physicians to use a uniform language to bill for their work.13 CPT codes also aid in determining reimbursement for a wide variety of physician services. Each CPT code has an associated number of RVUs attributed to it. RVUs are not static, but rather re-established at least every 5 years by CMS, as mandated by federal law.14 Physicians have a significant influence over this process through a committee called the RUC. The RUC is a committee of the AMA, composed of 32 total members, with 22 members appointed by national medical specialty societies – including emergency medicine which has one permanent seat on the RUC. ACEP, as the representative of the specialty in the AMA House of Delegates, funds the team that represents the specialty in this venue. There are 4 rotating seats, including 1 seat for a primary care specialty, 2 for internal medicine subspecialties, and 1 other specialty.15,16 Members of the RUC listen to presentations from specialty advisors, based on survey data, and then vote on proposed RVU values and service times to make their recommendations to CMS. Using the recommendations provided by the RUC, Medicare determines the value of each service or procedure by assigning an amount of RVUs. The RUC recommendations are highly influential on the ultimate compensation decisions made by CMS. According to the AMA, in most years, over 90% of RUC recommendations are adopted by CMS.17

There have been concerns that the membership structure of the RUC over-represents specialties, particularly surgical subspecialties, thereby potentially leading to higher values for procedures over cognitive work (such as an office visit). The RUC defines work as “intensity over time”, which is why a high-intensity procedure like endotracheal intubation (code 31500) will have a higher work RVU at 3.00 than a level three ED visit (code 99283) at 1.60. This is why it is important that you capture all of the work that you do in the emergency department setting, whether that be EKG review, suture placement, dislocation reduction, or intubation. Any and all procedures should be documented. In addition to just being good medicine, it is good business and will be expected by your employer.

RVUs comprise three factors: Physician Work + Practice Expense (facility) + Liability Insurance (malpractice). Together, these add to the “Total RVU.” However, RVUs are altered based on the location of practice to adjust for cost of living – called the Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI). Finally, when total RVUs have been calculated and adjusted based on the GPCI, they are multiplied by the Medicare conversion factor (CF) to arrive at the final payment. The Medicare CF is updated annually.18 For 2022, CMS has set Medicare payments at $34.6062 per total RVU. For example 99285, a common CPT code for high-intensity ED visits, is worth 5.17 RVUs, which would reimburse $178.91 in 2022.19

In emergency medicine, visits are coded with 1 of 5 CPT codes for evaluation and management of the patient based on the intensity of the visit (Level 1, 99281, is the least intense visit possible; level 5, 99285, is the most intense). Intensity represents the amount of work done in a certain amount of time, so high-acuity conditions requiring prompt and complex workups and timely treatment are considered more intense. Billers and coders determine intensity through a combination of the acuity of the patient’s presentation and the complexity of the medical work-up required to arrive at the diagnosis and treatment provided. This is the payment for the “cognitive” work of emergency medicine.19

Physicians are also reimbursed for the “physical” work of emergency medicine. Physicians can be reimbursed for procedures performed, such as intubations, laceration repairs, procedural sedation, and central lines. Most procedures performed in the ED have an associated CPT code and can be reimbursed separately.19 Additionally, ultrasound exams and your independent interpretation of diagnostic studies (eg, ECGs) can be billed using procedure codes.20 Of course, the work of each procedure must be appropriately documented to generate RVUs.19

Additionally, physicians may bill for critical care time when providing care for a patient with a critical illness. A “critical illness” is a presentation with a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in condition. These codes are unique in that they are time-based, allowing emergency physicians to bill for the amount of time they spend in the management of these patients. The first 30 to 74 minutes of care are coded with CPT code 99291, and each additional 30-minute interval of time after 105 minutes can be separately billed and reported using 99292. Of note, critical care time excludes time spent on separately billable procedures as well as teaching time.21

However, payments are not as simple as coding and billing for a set CPT. The documentation created in the medical record by the physician needs to support the code being billed by demonstrating the intensity of the medical decision-making (MDM) involved in patient care.19

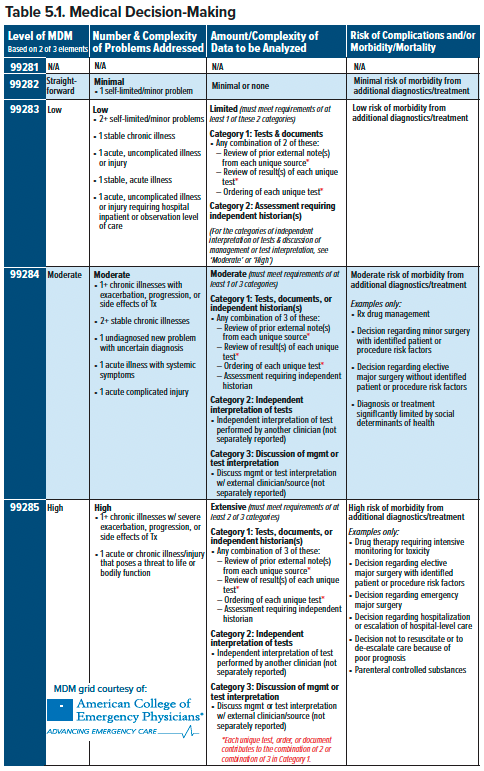

Assessing the intensity of the MDM consists of 3 components:22

- Number and Complexity of Problems Addressed

- Amount and/or Complexity of Data to be Reviewed and Analyzed

- Risk of Complications / Morbidity / Mortality of Patient Management

Level 1 visits (99281) are defined as visits for which the evaluation and management of the patient may not require the presence of a physician or qualified health care professional, while Level 5 visits (99285) are defined as those that require high-intensity medical decision-making. Levels 2-4 are visits requiring straightforward, low, and moderate medical decision-making, respectively.19

The “Number and Complexity of Problems Addressed” component attempts to quantify the overall complexity of the medical problems identified during a visit. Essentially, higher acuity problems and multiple problems qualify for increased complexity (see Table 5.1).

The “Amount and/or Complexity of Data to be Reviewed and Analyzed” section quantifies how much work went into interpreting the data for a visit. There are 3 levels of complexity (Limited, Moderate, Extensive) in this component. Each level of complexity has requirements for the number and categories of data that must be documented. Data is organized into 3 categories.

- Category 1 consists of ordering tests, interpretation tests, reviewing outside documents, orders, and/or obtaining history from non-patient sources, who are designated as independent historians.

- Category 2 is your independent interpretation of tests such as EKGs, ultrasound, or a chest X-ray as long as you do not bill it separately (ie, you cannot bill for your interpretation of an EKG and include it in your complexity score).

- Category 3 includes instances when you discuss interpretation or management of a test with an “external physician/other appropriate source,” which is most often a consultant or admitting physician in emergency medicine.

The “Risk of Complications / Morbidity / Mortality of Patient Management” component attempts to quantify the potential seriousness of consequences of patient management decisions. There are four tiers: minimal, low, moderate, and high. The decision to administer medications or perform bedside procedures can contribute to risk. Additionally, social determinants of health that affect treatment, if appropriately documented, can also increase the risk tier. Generally, more involved procedures or management decisions contribute to an increased risk tier.

To determine the appropriate MDM complexity, each of the 3 sub-components is assigned the appropriate score. Each MDM has corresponding requirements for each sub-component. To qualify for a particular MDM complexity, a physician must meet the required level in 2 of 3 of the sub-components. The visit is billed at the highest MDM complexity for which it qualifies.

Under the system that had been in place since 1995, there was a required minimum documentation for the history of present illness, review of systems, past medical history, social and family history, and review of systems to qualify for each E&M code. These imposing requirements will no longer be mandatory under the new 2023 guidelines. Instead, billing code selection will be based only on medical decision-making. However, a medically appropriate history and/or physical exam should still be documented, which will help guide coders and auditors to understanding the complexity of the medical issues being addressed as well as provide clear communication to our medical colleagues.22

A high-intensity diagnosis alone is not enough to qualify for a high-intensity visit; the documentation created by the emergency physician must capture enough of the work and medical decision-making that contributed to the patient’s care to justify the diagnosis. Insurance companies will "downcode," or decrease the billing level and compensation provided, if the available documentation is insufficient to justify the code billed.19

Moving Forward

The EMRA Representative Council has voted repeatedly to enhance trainees’ understanding of the factors affecting their livelihood. Two policies in particular are key:

- Section VI – Resident and Medical Student Education, IV. Financial Literacy Among Residents

EMRA will advocate for further resources and research will be allocated toward improving financial literacy among residents.23

- Section VI – Resident and Medical Student Education, VIII. Resident Indebtedness

The cost of medical education is ever-increasing, and medical students are entering residency with increasing levels of debt. This substantial education debt often impacts the residency experience as residents attempt to begin repayment on these loans. Efforts should be made to increase the tax deductibility of student loan payments, reinstate residency loan forbearance and deferment, and recognize emergency medicine as eligible for state and federal loan relief programs.23

It is crucial that physicians continue advocacy efforts concerning payment models, as these have a significant impact on compensation. There have been ongoing conversations about potential new models of compensation, known as Alternate Payment Models (APMs). This has been spurred by CMS’ ongoing movement away from fee-for-service compensation and toward value-based care, rewarding better care and better outcomes.24

ACEP has put forth an EM-specific APM called the Acute Unscheduled Care Model (AUCM), which represents a step closer to true value-based care.25 AUCM highlights the unique ability of the ED, with the appropriate tools, resources, and data, to safely discharge patients instead of having to admit them, and thereby realize significant health care savings. AUCM increases payments towards emergency physician groups who successfully reduce Medicare expenditures by reducing avoidable hospital admissions, improving post-discharge services, while still avoiding post-discharge adverse events.26 Potential adoption or adaptation of this plan remains under the discretion of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI).27 While this model offers an opportunity to compensate emergency physicians who provide high-quality and lower-cost care, it is still built on the foundation of fee-for-service billing.

Changes to the current payment structure will be implemented over the years to come. Physicians must be at the forefront, ensuring that we create the appropriate financial incentives that will drive a positive future for emergency medicine while minimizing unintended consequences.

TAKEAWAYS

- Physicians are paid in units of productivity known as RVUs that are influenced by an organization called the RUC.

- Level of intensity and thus reimbursement for ED visits is determined by a combination of their level of acuity, how much workup is necessary, and the risk inherent in the patient’s presentation.

- Emergency physicians are also reimbursed separately for procedures we perform.

- The future of physician payments during the transition from fee-for-service to value-based care remains uncertain.

- Physicians must be at the forefront of policy discussions concerning their compensation.

References

- Moseley III GB. The U.S. Health Care Non-System, 1908-2008. AMA J Ethics. 2008;10(5):324-331.

- Timeline: History of health reform in the U.S. - KFF. https://kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/5-02-13-history-of-health-reform.pdf. Published May 2, 2013. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Morrisey M. Chapter 1: History of Health Insurance in the United States. In: Health Insurance, Second Edition. Chicago, Illinois: Health Administration Press; 2013:3-25.

- Chapin C. The Conflicted Construction of Blue Shield: Caught between Blue Cross and the AMA. In Ensuring America's Health: The Public Creation of the Corporate Health Care System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;2015:122-153.

- Blumenthal D. Employer-sponsored health insurance in the United States--origins and implications. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):82-88.

- Preskitt JT. Health care reimbursement: Clemens to Clinton. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(1):40-44.

- Barnes J. Moving Away From Fee-for-Service. The Atlantic. Published 2012. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Thomasson M. From Sickness to Health: The Twentieth-Century Development of U.S. Health Insurance. Explor Econ Hist. 2002;39(3):233-253.

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Milestones 1937-2015. Published 2015.

- Medicare agency renamed as prelude to reforms. June 14, 2001.

- Hsiao WC, Braun P, Dunn D, Becker ER. Resource-Based Relative Values: An Overview. 1988;260(16):2347–2353.

- Ginsburg P. Fee-For-Service Will Remain A Feature Of Major Payment Reforms, Requiring More Changes In Medicare Physician Payment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(9):1977-1983.

- American Medical Association. CPT® overview and code approval. June 25, 2019.

- Baadh A, Peterkin Y, Wegener M, Flug J, Katz D, Hoffmann J. The Relative Value Unit: History, Current Use, and Controversies. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2016;45(2):128-132.

- American Medical Association. Composition of the RVS Update Committee (RUC). July 12, 2022.

- American Medical Association. An Introduction to the RUC. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- American Medical Association. RVS Update Process. 2022.

- What Are Relative Value Units (RVUs)? Published 2022. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- What Every Graduating Resident Needs To Know About Reimbursement. Published 2022. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- X-Ray - EKG FAQ. Published December 2021. https://www.acep.org/administration/reimbursement/reimbursement-faqs/x-ray---ekg-faq/

- Critical Care FAQ. Published December 2021. https://www.acep.org/administration/reimbursement/reimbursement-faqs/critical-care-faq/

- 2023 Emergency Department Evaluation and Management Guidelines. (2022, October). https://www.acep.org/administration/reimbursement/reimbursement-faqs/2023-ed-em-guidelines-faqs/

- Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association. EMRA Policy Compendium. Published November 2021. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- APMs - What is APMs (Advanced Alternative Payment Models). May 6, 2022.

- Davis J. Acute Unscheduled Care Model. ACEP. Published 2020. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Baehr A, Nedza S, Bettinger J, Marshall Vaskas H, Pilgrim R, Wiler J. Enhancing appropriate admissions: An advanced alternative payment model for emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;75(5):612-614.

- Davis J. CMS Innovation Center's vision for the future: How does ACEP's awesome "AUCM" model fit in? American College of Emergency Physicians. Published December 2, 2021. Accessed June 1, 2022.