Ch. 11. Medical Malpractice: The Sword of Damocles

Lindsay Davis, DO, MPH; Ranjit Singh, DO; Ramnik S. Dhaliwal, MD, JD

Chapter 11. Medical Malpractice: The Sword of Damocles

Recorded by Lauren Rosenfeld, MD | George Washington University

Medical malpractice can have devastating effects financially and psychologically on the emergency physician. Laws vary significantly state by state, but the good news is reform is possible and has been shown to be effective at reducing the burden on physicians.

Emergency medicine is a high-risk specialty for medical malpractice, with 1 out of every 14 emergency physicians getting sued each year. Learn how to be an effective advocate in your state, as most malpractice laws are at the state level.

Why It Matters to EM and ME

Anyone can sue you for anything, creating cost to you, using up your time and resources, but they still must demonstrate the four key elements to prove that you committed medical malpractice: that you had a duty to treat, that there was a breach of duty, that damages occurred, and that you caused those damages.1 As an emergency physician you have a 52% chance of being named in a malpractice suit during your career.2 This high probability should concern all emergency physicians. According to one study, compared to other specialties, emergency physicians are the third most likely to be sued, behind only general surgery and obstetrics/gynecology.2 Jena and colleagues found a different conclusion, showing that emergency physicians have a near-average likelihood of being sued, far behind many other specialties, and have a lower-than-average payout when sued.3 Emergency physicians have a median payout under $100,000 and mean under $200,000 compared to the mean for all physicians nearing almost $300,000.3 The most common malpractice claims for emergency medicine are diagnosis-related, representing 58% of claims, while 25% of claims are procedure-related.4 Malpractice premiums for emergency physicians vary widely from state to state, from as little as $8,000/year in South Dakota, Minnesota, and Nebraska to more than $40,000/year in Delaware and Georgia.5 These premiums and payouts are a significant burden to the financial health of a practice and are not limited to just direct costs, but further, cause loss of revenue from time off and loss of reputation. Lawyers tend to work on a contingency basis, meaning they receive a percentage of settlement if a case results in a payout.6 Lawyers will charge 33-40% of the awarded amount plus additional fees for costs, leaving patients less than two-thirds of the settlement.7 The current malpractice system, while stressful for doctors, also may leave patients and families with settlements that do not meet their financial needs.

How We Got to This Point

In the United States, medical malpractice claims began showing up in the early 1800s,8 but the legal issue of medical malpractice goes back in history to as early as the Code of Hammurabi in 2030 BC. In this code, there were very severe penalties for malpractice; a surgeon could lose his hands if the patient died. These penalties were awarded after a case was adjudicated before one or a panel of judges, depending on the severity of the accusation. As today, though, the most common of penalties was monetary.9 Four-thousand years later we saw the explosion of medical malpractice claims in the courts in the 1960s in the United States.8 The medical malpractice system is a subset of U.S. tort law, which refers to laws involving suffering of harm due to wrongful acts by another.10 In 2011, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) recognized a growing problem with medical malpractice and created goals for reforms of the system to limit cost, deter medical errors, and to ensure fair compensation for harmed patients.11

There are three types of damages that patients can recover in medical malpractice cases. These fall into the category of economic, non-economic, and punitive damages. Economic damages include the monetary losses the plaintiff has incurred or is likely to incur in the future. This includes costs of medical care and lost wages. Non-economic damages account for an injured person’s pain, emotional distress, suffering, or other similar issues related to an accident. This can include actual, future, and punitive, but is not supposed to include speculative damages. Punitive damages may be sought if the plaintiff claims the physician practiced with an intent to harm rather than with simple negligence. Caps on non-economic damages (ie, “pain and suffering”) place limitations on the monetary compensation a plaintiff can receive following a malpractice claim.

Thirty-three states have enacted caps on damages ranging from $250,000 to over $1,000,000 mostly on non-economic awards, while 16 states still do not have monetary caps on medical malpractice.11 Minnesota and Connecticut do not have specific limits but do have a court review process to limit monetary penalties.11 The NCSL brief found that low damage caps, restrictive statutes of limitation, and stringent expert witness requirements were associated with the lowest levels of malpractice payments.12 Medical liability laws have fallen to states, resulting in a wide variety of types of liability reform. In 2013 and 2014, Dr. Gregory Roslund compiled a 4-part series of articles discussing the current changes to medical malpractice and a detailed discussion of laws and effect on emergency physicians in all 50 states.5 At the time he showed that states from Florida and Missouri to Massachusetts and Oregon were passing laws that were greatly changing the state of medical malpractice in each state, from overturning caps on non-economic damages (Florida) and ruling damage caps unconstitutional (Missouri) to passing early disclosure, apology and offering laws (Massachusetts and Oregon).5 Many states with medical malpractice laws that reduce economic damages to physicians and place higher burdens on expert witnesses, such as Texas, Pennsylvania, and Mississippi, have seen dramatic decreases in medical malpractice claims and, in turn, significant decreases in cost and burden on emergency physicians.5

Current State of the Issue

Medical malpractice law varies across different jurisdictions from state to state. Despite this fragmentation and wide variability from state to state, several principles must still apply in all cases. This includes the injured patient must show during legal proceedings that there was a duty by the physician, the physician breached that duty, that breach caused injury, and that there were resulting damages.1 A duty by the physician is established once there is a relationship formed between the physician and the patient in a medical setting. This duty can be formed not only when a physician is caring for their own patients but also when a physician is covering patients for a colleague or covering a clinic. Breach of duty must be shown by the patient when there is deviation from the standard of care. This is usually defined as care that a similarly situated physician would have provided to the patient had they been the treating physician. In most cases, an expert witness provides information about the standard of care in similar medical settings and explains how there was deviation in the case before the jury, causing subsequent injury. Resulting damages are usually measured in monetary damages, since those are usually more easily calculated and administered. Punitive damages are rare in medical malpractice cases and are usually reserved by courts for more egregious conduct that society has a particular interest in deterring, such as destruction of medical records or sexual misconduct towards a patient.

According to the Medical Malpractice Report by the National Practitioner Data Bank,14 in 2018, plaintiffs received more than $4 billion in malpractice lawsuits collectively. The majority of the payouts were from settlements, 96.5%, while 3.5% resulted from court judgments. The good news for physicians is that medical malpractice claims have been on the decline since around 2001 in both number of lawsuits and amount paid out.15 Across specialties, 7.4% of physicians annually had a claim, whereas 1.6% made an indemnity payment. There was significant variation across specialties in the probability of facing a claim. Amongst the specialties, emergency medicine ranked lower than surgical specialties and was similar to internal medicine.3

Malpractice laws vary significantly from state to state, so the risk that an emergency physician faces will depend on where they practice. Several states such as Texas, California, Nevada, and Indiana have enacted caps on noneconomic damages. These states have shown success at reducing payments to plaintiffs and reducing the cost of malpractice insurance premiums for physicians. The effects of noneconomic damage caps on premiums vary according to the amount of the cap.16 Compared to no cap, a cap of $500,000 did not show a statistically significant reduction in malpractice insurance premiums, while a $250,000 cap successfully reduced malpractice insurance premiums by 20%. Reducing the overall cost of lawsuits has been demonstrated to decrease the costs incurred by physicians practicing defensive medicine, which is about $50 billion to $65 billion annually.17

Physicians are torn between the competing interests of minimizing health care costs for patients and minimizing their own liability by practicing defensive medicine (eg, ordering potentially unnecessary diagnostic tests). Threatened by the rising price of liability insurance and the negative impact the medical malpractice environment has on access to physicians, many medical societies have advocated for legislative action that would ensure a balanced medical malpractice environment. These advocacy efforts eventually gave rise to “tort reform” in several states, leading to legislative changes to state laws governing medical liability.18 These reforms on medical liability have been crucial for controlling burdensome rising malpractice premiums and protecting physicians from the burden of frivolous malpractice cases.19

Moving Forward

Emergency medicine is a high-risk specialty for medical malpractice, with 1 out of every 14 emergency physicians getting sued each year.3 As physicians, we are also advocates for our patients. As such, the focus of medical malpractice reform should focus on ensuring patients who are harmed by medical malpractice are made whole, but unnecessary or excessive payouts should be limited. Medical malpractice reforms can decrease financial burden on the health care system, reduce defensive medicine, and also ensure that patients receive fair compensation to meet their needs after a medical error or harm has occurred.

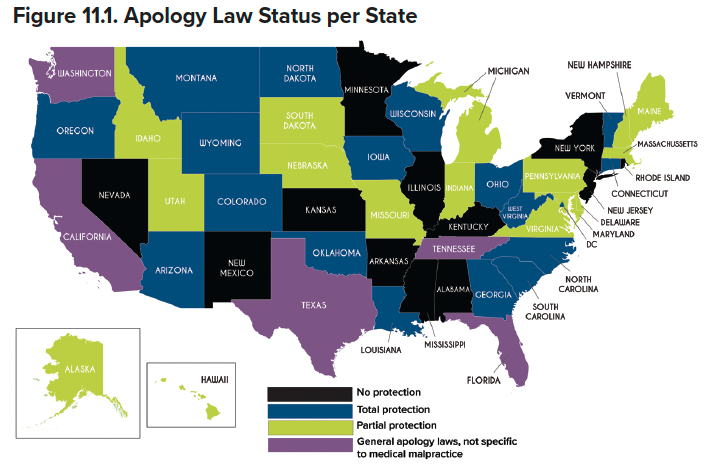

There are many ways to change the overall medical malpractice landscape and create improvements for both emergency physicians and our patients. “Apology laws” are one type or reform, which allow physicians to make apologetic statements to their patients about bad outcomes or medical errors without their statement being admissible in court, should the patient or family later choose to pursue a malpractice claim. The impetus behind the first apology law, enacted in Massachusetts in 1986, was to encourage open communication and empathy – which can go a long way toward repairing the doctor-patient relationship and staving off litigation. In turn, reducing the number of lawsuits and their payouts can help avoid the increased costs created by the practice of defensive medicine.

Emergency medicine residents should receive education on specific state liability laws, especially pertaining to how we communicate with patients. In “When and Where to Say I’m Sorry,” the Center for Litigation Management offers an overview of how each U.S. state and territory views apologies when speaking with patients.20 The distinction between empathizing and admitting liability varies greatly by state; 18 states offer total protection, while 12 have no apology laws at all – meaning any statements made to patients can be used in court.20

In addition to apology laws, there are numerous other ways to achieve medical malpractice reform. Caps on damages, as mentioned above, limit the amount of money that a plaintiff can receive from a malpractice lawsuit, and are currently the most prevalent type of malpractice reform.21 Limits on attorney’s fees can increase the amount of compensation that a patient receives, rather than their attorney. Both of these interventions can limit the filing of frivolous lawsuits as attorneys will be less likely to pursue cases on a contingency basis if they face limits to the payout that they may receive. An abundance of evidence has shown that tort reforms, such as caps on non-economic damages and reduction of the statute of limitations can reduce the cost of malpractice insurance premiums and increase access to care for patients.17

Additional less prevalent but innovative ways of achieving liability reform include:22

- Health courts (specialized courts for handling malpractice claims)

- Pre-trial screening panels (early review to determine if a claim has sufficient merit to proceed to trial; also known as an affidavit or certificate of merit)

- Liability safe harbors for the practice of evidence-based medicine (protections for physicians following established guidelines)

- Expert witness qualification requirements

- Early disclosure and compensation programs

ACEP has a long history of supporting tort reform. ACEP policy supports a broad variety of tort reforms, including caps on non-economic damages, controls on attorney’s fees, immunity for following guidelines, apology laws, and expert witness requirements. To specifically address liability in emergency situations, ACEP has supported legislation that would offer emergency and on-call physicians who provide EMTALA-related services with temporary protections under the Federal Tort Claims Act.23

TAKEAWAYS

- Most emergency physicians will face a medical malpractice lawsuit at some point in their career.

- Be familiar with the malpractice laws in the state in which you practice, and in any state you are considering for future practice.

- Learn how to be an effective advocate in your state, as most malpractice laws are at the state level.

- Advocate for reforms that will help emergency physicians while understanding how the changes improve care for patients by increasing access to care and decreasing health care costs.

References

- Bal BS. An introduction to medical malpractice in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(2):339-347.

- Guardado J. Policy research perspectives - Medical Liability Claim Frequency Among U.S. Physicians. AMA. 2017.

- Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636.

- Myers LC, Einbinder J, Camargo CA Jr, Aaronson EL. Characteristics of medical malpractice claims involving emergency medicine physicians. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2021;41(1):9-15.

- Roslund G. Medical Liability and the Emergency Physician: A State by State Comparison — Part 1-4. AAEM. 2013.

- Fisher TL. Medical malpractice in the United States: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1974;110(1):102-103.

- Suszek A. How will you pay a medical malpractice lawyer? AllLaw.

- Kass J, Rose R. Medical malpractice reform—historical approaches, alternative models, and communication and Resolution Programs. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(3):299-310.

- Halwani TM, Takrouri MSM. Medical Laws and Ethics of Babylon as Read in Hammurabi's Code (History). Internet J Law, Healthcare and Ethics. December 31, 2006.

- Tort law. The Free Dictionary. Accessed June 6, 2022.

- Morton H. Medical Liability/Medical Malpractice Laws. National Conference of State Legislatures. 2021.

- Medical Malpractice Reform. Health Cost Containment and Efficiencies. National Conference of State Legislatures. 2011.

- The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. NOTE: Mar. 23, 2010 - [H.R. 3590] (2010).

- S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Practitioner Data Bank.

- Schaffer A, Jena AB, Seabury SA, Singh H, Chalasani V, Kachalia A. Rates and Characteristics of Paid Malpractice Claims among Us Physicians by Specialty, 1992-2014. JAMA Int Med. 2017; 177(5):710-719.

- Seabury SA, Helland E, Jena AB. Medical Malpractice Reform: Noneconomic Damages Caps Reduced Payments 15 Percent, With Varied Effects By Specialty. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(11):2048–2056.

- Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569-1577.

- Singh R, Solanki J. Has tort reform been effective in abating the medical malpractice crisis? An empirical analysis from 1991-2012. Duke University. April 2014.

- Hubbard FP. The Nature and Impact of the “Tort Reform” Movement. Hofstra Law Review. 2006;35(2):4.

- Center for Litigation Management. When and Where to Say I’m Sorry. Feb. 16, 2021.

- Medical Liability Reform NOW: The facts you need to know to address the broken medical liability system. 2022. Accessed at https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/mlr-now.pdf.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Medical malpractice: Impact of the crisis and effect of state tort reforms. Research Synthesis Report No. 10, May 2006.

- EMTALA Services Medical Liability Reform (HR836). Accessed at https://www.acep.org/federal-advocacy/liability-reform/emtala-services-medical-liability-reform-hr836/.