Ch. 1. Anyone, Anything, Anytime: The EMTALA Story

Moira Smith, MD, MPH; Cameron Grossaint, DO; Sachin Santhakumar, MD

Chapter 1. Anyone, Anything, Anytime: The EMTALA Story

Recorded by Moira Smith, MD, MPH | University of Virginia

Anyone, anything, anytime. This is the founding ethos of emergency medicine, and its legal basis can be found in the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA). The law established definitions for a medical screening exam, stabilization, and criteria for transfer, which together influenced a large portion of emergency medical practice. However, as an unfunded mandate for care, it transfers the costs of insufficient access to care to emergency departments and the clinicians.

Through EMTALA, emergency medicine retains the ethos of “anyone, anything, anytime.” The ED is open every single hour of every day – for everyone. EMTALA creates the legal basis for this commitment.

Why It Matters to EM and ME

Emergency departments are critical to the American health care system. As the most common entry point for the uninsured and acutely ill, EDs care for any patient who walks through the doors. According to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), between 2007-2018, U.S. EDs accounted for an average of 130 million visits annually.1,2 To ensure this unequivocal right to emergency care, Congress passed the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act in 1986, an unfunded mandate that guarantees a screening exam and stabilizing treatment, including hospitalization. This obligation applied to anyone who walked into a hospital-based ED, without regard for the ability to pay, making the ED a “safety net” for those who may have no other place to receive care.

The policy remains controversial, as its scope continues to expand yet remains unfunded, costing hospitals, physicians, and ultimately insured patients an exorbitant amount. According to a 2003 report from the Center for Health Policy Research, an emergency physician in the United States donates on average about $140,000 each year in uncompensated EMTALA-mandated care — more than 10 times the all-specialty average.1

Taken in the aggregate, the amount of uncompensated care provided in emergency departments has exceeded $50 billion annually.3

Even as individual emergency physicians provide more uncompensated care than others, they also face the real risk of fines that can apply to both the institution and the individual. These fines, in addition to the true nuclear option of removal of CMS reimbursement for an organization or individual, makes the stakes for meeting EMTALA requirements substantial. Both the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Office of Inspector General (OIG) have administrative enforcement powers with regard to EMTALA violations. There is a 2-year statute of limitations for civil enforcement of any violation. Penalties may include:4

- Hospital fines up to $104,826 per violation ($25,000 for a hospital with fewer than 100 beds)

- Physician fines of up to $50,000 per violation (includes on-call physicians)

- Hospital opened to personal injury lawsuits in civil court under a “private cause of action” clause

- Termination of the hospital or physician’s Medicare provider agreement

EMTALA also requires that a patient be transferred to a higher level of care when the initial facility does not have the necessary services or specialists. Often this transfer is from a community site to a tertiary care center. However, this can also apply to transfers from one tertiary care center to another if the first facility lacks subspecialty care that is critical for the patient. Notably, EMTALA does not apply to the transfer of stable patients or care of a stabilized patient.

How We Got to This Point

EMTALA was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan on April 7, 1986, as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) of 1985. The act was passed in response to the widespread practice of “patient dumping” from mostly private community hospitals to county hospitals. At the time, 250,000 people a year were transferred based on their lack of availability to pay for care.5 This leads to an unbalanced effect on patients from certain socio-economic backgrounds. Cook County, for example, noted 89% of patient transfers were minorities, 87% lacked employment, only 6% of these patients had given consent for transfer, and 24% of patients transferred had unstable conditions. Patients were twice as likely to die as a result of transfer.5

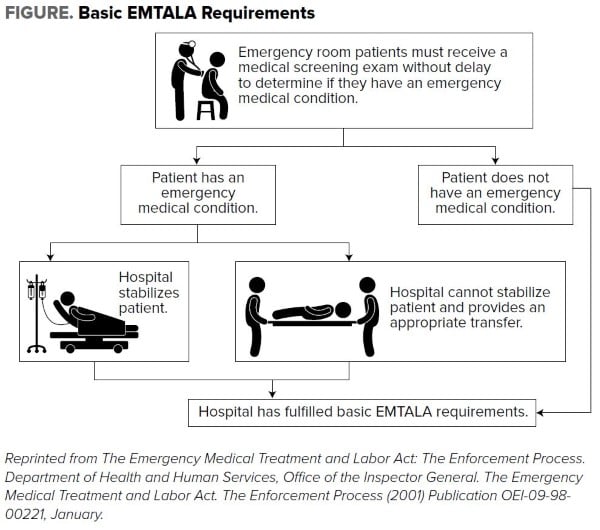

EMTALA established the following three main obligations:

- For any person who comes to a hospital emergency department, the hospital must provide for an appropriate medical screening examination… to determine whether or not an emergency medical condition exists.

- If an emergency medical condition exists, the hospital must stabilize the medical condition within its facilities or initiate an appropriate transfer to a facility capable of treating the patient.

- Hospitals with more specialized capabilities are obligated to accept appropriate transfers of patients if they have the capacity to treat the patients.

EMTALA defines an emergency medical condition (EMC) as “a condition manifesting itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity (including severe pain) such that the absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably be expected to result in placing the individual’s health (or the health of an unborn child) in serious jeopardy, serious impairment to bodily functions, or serious dysfunction of bodily organs.”4

Medical Screening Examination (MSE)

All patients, regardless of insurance status, are entitled to an MSE if they are on a “hospital campus.” Through its inception, EMTALA has gradually defined this to be potentially anywhere on a hospital campus and within 250 yards of a hospital building. This would also include EMS vehicles owned or operated

by the hospital. Furthermore, a court appeals decision in 2001 Arrington v. Wong found this could include virtually any EMS service as well.

EMTALA requires an appropriate MSE for every person who seeks care at an emergency department, with a mandate to offer treatment “within the capability of the hospital, including ancillary services routinely available to the emergency department to determine if an emergency medical condition exists.” If a patient is found to not have any EMCs, EMTALA no longer applies. Nursing triage alone does not meet the obligation to provide an MSE unless the nursing staff has been elevated to membership in the medical staff.

MSE has been difficult to interpret, as neither the courts nor the Health Care Finance Administration have specifically detailed it. In general, an adequate MSE depends on the presenting symptoms and the normal standard of care required for such a case (vital sign monitoring, labwork, imaging, history and physical exam, consults). The biggest factor that must be satisfied is: Was the screening exam for a patient’s complaint similar to all patients, regardless of other factors such as insurance or ability to pay? In short, was the standard of care followed? The use of protocols in hospitals has been particularly helpful in MSEs, as they standardized patient care. Because protocols may vary according to patient encounter and complaint, any deviation must be documented and justified, as it can be considered evidence for an EMTALA violation.6

Stabilization

All Medicare-participating hospitals must stabilize a patient if an EMC exists. Stabilization under the law is “treatment as necessary to assure, within reasonable medical probability, that no material deterioration of the condition is likely to result from or occur during the transfer of an individual from a facility or that [a person in active labor] has delivered the child and placenta.” If MSE reveals any EMC, stabilize the medical condition of the individual within the capabilities of the staff and facilities available at the hospital, prior to discharge or transfer without any clinical deterioration. Depending on the clinical picture, this step can take anywhere from hours to days to months. Stabilizing a patient often requires consultants from other specialties, which means the EMTALA requirements and penalties extend to them as well. Stabilization does not require a medical condition to be resolved. After stabilization, EMTALA no longer applies.

Appropriate Transfers

If an EMC is found, a hospital must provide the medical treatment necessary to stabilize the patient or, if outside the capabilities of the hospital, transfer the patient to another facility capable of stabilizing the patient. The transfer must follow these criteria, often captured in standard transfer forms:

- The transferring hospital provides medical treatment to minimize risk to the individual or unborn child’s health.

- The receiving hospital has available space, qualified personnel, and has agreed to accept and provide treatment.

- The transferring hospital sends all available documents related to the EMC to the receiving hospital.

- The transfer is effected through the use of qualified personnel and appropriate transportation equipment.

- The transfer meets any other CMS requirement necessary in the interest of the individual being transferred.

Institutions must be aware of the nondiscrimination provisions, in which hospitals with specialized capabilities (NICU, burn center, trauma, etc.) must accept an appropriate transfer who requires the need for such care, if the hospital has the capacity to treat the individual.6 If an individual or a representative of the patient refuses to consent to treatment and/or transfer after explaining the risks and benefits, then EMTALA obligation is considered to have been met. If a patient with an EMC is unstable for transfer and a provider refuses to authorize the transfer, the hospital cannot penalize that provider.

Specialty Obligation

The federal statute mandates all U.S. hospitals that participate in the Medicare program “maintain a list of physicians who are on-call for duty after the initial examination to provide further evaluation and/or treatment necessary to stabilize an individual with an emergency medical condition.” If a hospital offers a specialty coverage to the public, then the service is expected to be available through on-call coverage of the emergency department.

Current State of the Issue

EMTALA is still currently an unfunded mandate, meaning there is no designated funding to cover the "safety net" care that EMTALA ensures. The expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act has increased coverage, but a significant portion of the cost is absorbed by individual hospitals and health care systems as well as taxpayers.

EMTALA was based on an assumption that capacity would be available somewhere within the health care system if a particular hospital could not provide the care a patient needed. By its nature as an anti-dumping law, it assumed there existed private hospitals with beds to accept these patients. In recent years, gradually increasing overcrowding at hospitals has been testing this assumption, leading hospitals to be at capacity more often and "closed" to transfers and admissions. This was only accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent staffing difficulties. Suddenly, not only did individual hospitals not have capacity, but sometimes entire cities, states, and even regions did not. As a result, there was flexibility added to EMTALA through blanket waivers. These allowed hospitals to modify the indicated parts of EMTALA without going through an approval process with CMS. Notably, adjustments were allowed to direct or relocate a patient to another location for their MSE and to allow for unstable transfers as long as it was in accordance with the local emergency plan and given that plan all efforts were taken to minimize risk from the unstable transfer.7 While these changes are to be temporary, it appears the stresses on the capacity of our health care system are not. Thus the long-term impact on the application of EMTALA remains to be seen.

Through EMTALA, emergency medicine retains the ethos of anyone, anything, anytime. Emergency physicians see everything that encompasses the human experience, from the inception of life to death. Emergency medicine is an incredible field and the frontline of medicine. The ED is open every single hour of every day, for everyone – including the most vulnerable groups, from children suffering abuse to the elderly, uninsured, those without housing - anyone. Patients are seen under almost any circumstance as well, from mass casualties to pandemics. We provide a safety net for medicine by having the appropriate training and understanding of medicine to screen patients for emergent and critical conditions to elevate and deliver the care people need as soon as feasibly possible at any point in the day. It is EMTALA that creates the legal base that allows emergency medicine to hold to its ideals. This allows emergency medicine to play a critical role in the American health care system.

Moving Forward

EMTALA will continue to be a core component of the promise of emergency medicine to care for anyone, anything, anytime. Emergency medicine’s continued support of this legislation keeps with the commitment to our patients first, regardless of demographics, socio-economics, or insurance status. However, it is important to continue to advocate for sources of funding for patients who are otherwise unfunded. Alleviating this financial burden will allow emergency departments to further the services they can provide to all patients. It is also important recognize that there are those who are advocating for the elimination of EMTALA or significant modifications that could threaten the ability to continue to provide care to anyone, anything, anytime.

Additionally, EMTALA has far-reaching implications in many other aspects of health policy and emergency medicine practice. Recently this was most evident in discussions around insurance reimbursements. Given that emergency physicians have a mandate to see all patients, the typical dynamic of payers needing to negotiate with physicians in order for their customers to be able to access services no longer exists. Thus protections to reimbursement will rely on advocacy for protection from the government given the unique mandate from EMTALA.

TAKEAWAYS

- EMTALA ensures that every citizen can receive a minimum level of care in the emergency department – but it is an unfunded mandate, putting EM at the intersection of public policy and economics.

- It is crucial to advocate for policies that support clinicians who offer EMTALA-related unfunded care.

References

- Kane C. The Impact of EMTALA on Physician Practices. AMA PCPS Report from 2001. Feb. 2003.

- Cairns C, Ashman JJ, Kang K. Emergency department visit rates by selected characteristics: United States, 2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 401. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2021.

- EMTALA Fact Sheet. Accessed at https://www.acep.org/life-as-a-physician/ethics--legal/emtala/emtala-fact-sheet/.

- Ansell DA, Schiff RL. Patient Dumping: Status, Implications, and Policy Recommendations. JAMA. 1987;257(11):1500–1502.

- Smith JM. EMTALA basics: what medical professionals need to know. Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(6):426-429.

- Wright D. Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) Requirements and Implications Related to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. March 30, 2020. QSO-20-15. Accessed November 6, 2022.