Ch. 6. Patients as Payers

Kirstin Woody Scott, MD, MPhil, PhD; Pranav Kaul, MD; Michael Granovsky, MD, CPC, FACEP

Chapter 6. Patients as Payers

Recorded by Sonal Kumar | Ross University School of Medicine and Pranav Kaul, MD | Northwestern University

This chapter explores the complexities of the U.S. health care system, the mechanisms through which patients bear financial responsibility for the cost of their care, and also features some of the ongoing debates relevant to patients who wish to seek emergency care without fear of costs – including the challenges of being uninsured or underinsured when emergencies happen.

Various forms of cost-sharing, regardless of insurance status, can have a direct impact on the care that we provide ED patients. This can take the form of patients dreading the cost of the ED before they seek care, hesitating to seek care, and then – if they do seek care – feeling hesitant to accept the recommendations made by their emergency physician due to financial worries.

Why It Matters to EM and ME

The emergency department (ED) is the safety net of our health care system, seeing all patients regardless of their ability to pay. However, patients are increasingly worried about the cost of care, especially as it relates to acute, unscheduled health events. This has numerous implications for emergency physicians and their practice, both clinically and financially. Unlike other segments of the health care system, the ED is unique in that all patients receive treatment regardless of their ability to pay at the point of service, in accordance with the federal law known as EMTALA (see Chapter 1 for details). Consequently, emergency physicians deliver the largest amount of “charity care” compared to any other specialty.1 This model of service-before-payment may surprise patients who receive bills for their ED care long after the event took place, especially if they incorrectly assumed that a particular service was covered by their insurance plan. This has translated into heightened public awareness and concerns about ED costs, which has led to various state and national legislation, such as the No Surprises Act of 2020. Further, national and state emergency medicine organizations continue to face threats to what is known as the “prudent layperson” standard, which contends that physicians should be reimbursed for ED visits regardless of whether the patient was ultimately diagnosed with a medical emergency. Insurers sometimes retroactively deny these claims, despite very concerning presenting symptoms - leaving patients to solely cover the costs of their emergency care. Regardless of the cause, given the mechanisms by which patients are payers of health care services in the U.S. health care system, this can heighten patients’ fears about the cost of ED care in a way that can impact care-seeking behavior; patients may delay or even forego needed emergency medical care altogether due to fears of unpredictable or high costs.

How We Got to This Point

The U.S. health care “system” is complex, consisting of a patchwork of payers, physicians, hospitals, and others in the health care chain. Though the system has a number of strengths in terms of innovation and technological advancements in medicine (especially for those who can afford quality care), its complexity leads to inefficiencies that can be challenging for patients to navigate.2,3

Health care in the U.S. is the most expensive in the world (amounting to $4.1 trillion dollars in 2020).4 In spite of its strengths, the U.S. system’s health outcomes are not commensurate with the expense paid compared to similar nations.5 While spending trillions, the U.S. does not guarantee access to health care to all of its citizens and experiences myriad challenges with financing the high cost of care.5,6

Uneven access to health coverage in the U.S. is relevant to emergency physicians because the ED has been characterized as the “safety net” for millions of Americans.7 Everyone who arrives at the ED is entitled to a medical screening exam and to stabilizing treatment regardless of ability to pay. This requirement has been codified in federal law since 1986 for all hospitals reimbursed by Medicare, which is the largest payer of health care services in the U.S. and thus has immense influence on setting payment standards.8 This EMTALA requirement does not apply to outpatient clinics or ambulatory centers, or even to the Veterans’ Affairs Hospitals, as they do not rely on Medicare funding. Because of EMTALA, patients encounter no financial barriers to initially accessing emergency care unlike other clinical settings. However, patients are still ultimately responsible for the expenses incurred during an ED visit or subsequent hospitalization. This logistical mechanism of patients paying after an ED visit set the stage for why surprise billing, which is explained further below and in Chapter 8.

This chapter serves as a primer to explain that patients are still the payers in this complex system. To understand this, it is helpful to keep in mind three main categories of “payers” when you examine who is footing the bill for the trillions of dollars that circulate through the current U.S. health care system:

- Private payers (eg, commercial insurance - potentially obtained through one’s employer or through the individual market, such as HealthCare.gov Marketplaces, TRICARE, worker’s compensation). Commercial payers may be either for-profit or non-profit.

- Public payers (eg, Medicaid [a state-federal partnership for primarily low-income individuals]9), Medicare (for patients aged 65 and older or those with end-stage renal disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), Medicare Advantage (a privatized version of Medicare), other federal/state/local (eg, county hospitals and health systems, and Veterans Affairs).

- Individuals paying out-of-pocket payments (eg, those who are insured have out-of-pocket payments for health care such as deductibles, copays, or coinsurance as well as the uninsured “self-pay” patients who must pay all health care expenses out of pocket)

All patients - regardless of insurance status - are “payers” of health care services in some way. As such, it is helpful to understand how many individuals in the U.S. system are uninsured and thus have no financial risk protection from health care costs, especially in cases of acute, unscheduled care. As of 2021, more than 28 million Americans were uninsured, representing 8.8% of all Americans and 10.5% of those under the age of 65.11 While insurance coverage provisions such as the dependent coverage expansion, expansion of Medicaid, and creation of the health insurance marketplaces that were included in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) markedly reduced the uninsurance rate to all-time historic lows, coverage gaps still remain.11-13

When someone is uninsured (ie, “self-pay” patient), they have no contract with an insurer in place to protect them from the full charges associated with a particular health care service. Though uninsured patients do not pay monthly insurance premiums, their lack of insurance coverage means they are often subjected to list prices for the services they receive. Uninsured patients consistently face higher bills for health care services relative to other patients, including for ED care, and may be at risk of financial peril as a result.15-17

However, the 91% of Americans who currently have some form of health insurance are also still “payers” through various forms of cost-sharing. First, all insured patients pay a monthly premium (if insured through their employer, that premium cost may also be shared by the employer). Additionally, patients accrue financial responsibility at the point of service in the form of deductibles, co-payments, and co-insurance, which are defined as follows:

- Deductibles are the amount to be paid by the insured before most services are covered by their insurance plan.

- Copayments are a fixed amount paid by the insured at time of service.

- Coinsurance is the percentage of service costs paid by the insured after the deductible is met.18

The mechanism of cost-sharing varies dramatically by insurance type, but can be applicable to both public and private insurance plans.19,20 For example, each state can opt to include limited premiums or enrollment fees for certain low-income patients who qualify for Medicaid in an attempt to enforce some “personal responsibility” for paying for health care.19 However, research suggests deleterious effects of these cost-sharing mechanisms on low-income Medicaid enrollees, including evidence that out-of-pocket payments are associated with barriers to obtaining coverage, reductions in necessary care, and lack of visible cost savings to the state.21

Even insured patients who receive “in network” services face some degree of out-of-pocket costs for their health care. With rising health care costs and rising deductibles, many of these patients’ out-of-pocket contributions have increased over time.22

Current State of the Issue

The unique nature of emergency medicine’s ethical and legal commitment to not delay screening or treatment of emergencies due to one’s ability to pay at the point of service means that no payment is required up front by the patient in an ED. Given that the ACA made emergency services an “essential health benefit,” there is an expectation that it is essential and yet there is much variation in the specifics of how much insurance pays versus how much the patient pays once the service is provided.23,24

Americans have consistently ranked health care costs as a top financial worry.25 Data from the 2020 National Health Interview Survey showed that 1 in 11 Americans reported delaying or forgoing medical care due to health care costs, with these delays even more pronounced among low-income or uninsured Americans.26 Specifically, nearly 1 in 3 (30%) of uninsured Americans reported either forgoing or delaying care due to costs.26 However, even patients with insurance report concerns with medical bills. In December 2021, nearly half of Americans (46%) reported difficulty with paying out-of-pocket medical bills that were not covered by their insurance.25

This mixture of complexity, confusion, and concerns about costs overall, helped to fuel rising public attention and outcry on the topic of out-of-network balance billing ( or “surprise” billing) among patients with commercial private insurance.27,28 Balance billing is not permitted for Medicaid or Medicare. Though this practice was by no means limited to the specialty of emergency medicine (ie, the possibility and practice of balance billing exists across all specialties, including anesthesiology and primary care), prominent media coverage featured many cases of this happening in the setting of a patient being treated for a medical emergency.29

Due to challenging practices by some payers, some ED physicians have not been able to remain contracted as an “in-network” physician and thus are characterized as “out-of-network.”30 This exposes patients who are facing a medical emergency, even if located physically in an “in-network” hospital, to medical care by a physician who is not covered by their insurance contract. A 2019 study documenting trends of out-of-network billing in both EDs and inpatient hospitalizations from 2010-2016 showed this practice was happening more frequently and resulted in higher bills for patients over time.31 Given the mission of the ED to care for anyone at any time and regardless of ability to pay, this issue of surprise billing led the specialty of emergency medicine to support patient protections to correct this policy flaw.32,33

In early 2020, 65% of Americans reported they worried about unexpected medical bills.34 The majority of Americans supported federal action to protect patients from surprise medical bills, including when being taken to the ED by an out-of-network ambulance, when being taken to an out-of-network hospital in the case of an emergency, or when being treated by an out-of-network physician even at an in-network hospital.34 Responding to this outcry, Congress passed the No Surprises Act in 2020, which went into effect as of Jan. 1, 2022.35,36

Increasing evidence exists to show that out-of-pocket costs are on the rise for all patients, regardless of insurance status. Given the ED’s distinct role as a true safety net for uninsured patients, it is important to examine the evidence of the financial impact that emergencies can have on uninsured patients. Studies focusing on patients hospitalized for emergency conditions such as traumatic injury and acute coronary syndrome suggest that 80-90% of uninsured patients are at risk of receiving a bill that would qualify for what the World Health Organization has defined as a catastrophic health expenditure,37-39 defined as annual out-of-pocket health care spending that is greater than 40% of one’s post-subsistence (paying for housing and food) household income or 10% of one’s total annual household income.37,39 This measure of financial toxicity of health care was also the subject of a study focused on uninsured ED patients, which found that 1 in 5 uninsured patients were at risk of receiving a bill that met catastrophic health expenditure thresholds for a single treat-and-release ED visit.17

Though this risk of financial toxicity may be a predictable challenge of the U.S. health system for those who lack insurance, underinsurance also exposes patients to similar risks.40 Simply put, many insured Americans are struggling to afford health care, including some who are having difficulty paying for their hospitalizations after COVID-19.41 An important trend to consider when it comes to patients as payers is the growth of high-deductible health plans (HDHP). These insurance products were created with an intent to make patients more cost-conscious when seeking care.42 HDHPs are attractive to prospective buyers because they have lower premiums than traditional health insurance products. Between 2010 and 2020, there was an estimated 18% growth in the proportion of covered workers enrolled in an HDHP.43 As expected, those enrolled in HDHP insurance products have higher deductibles than those in other traditional insurance plans, such as health maintenance organization (HMO) or preferred provider organization (PPO) products.43 HDHPs can be paired with Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) that allow money used for certain medical payments to be exempt from federal taxes.44

Yet, if patients with a plan that could be categorized as an HDHP have any sort of emergency, they must pay for all health care expenditures until they meet the deductible. As of 2022, the Internal Revenue Service defines a HDHP as any plan with a deductible of $1400 for an individual (with yearly out-of-pocket max no more than $7050 for in-network services) or a deductible of $2800 for a family insurance plan (with a yearly out-of-pocket max no more than $14,100 for in-network services).44 The average annual deductible was $2454 for HSA-qualified HDHPs.43 While some customers opt for these high-deductible plans in order to pay lower monthly premiums, the tradeoff is inherent downstream risk. Recent studies have suggested that HDHPs with HSAs are a tax break benefitting healthier and wealthier populations.51 However, nearly two in three households report not having enough assets to pay for the deductible of some of the HDHP plans.40 When an emergency happens, patients can feel especially vulnerable since the cost of emergency care may require spending up to the top end of a “high” deductible.

Another critically important payer of ED care is Medicaid. Evidence suggests that those under the age of 65 with Medicaid are twice as likely to go to the ED for care relative to the privately insured.45 However, there have been many policies affecting this diverse program managed by each state that can lead to cost sharing among Medicaid patients. For example, states can impose higher copayments for Medicaid patients when they have sought emergency care in situations that retroactively are later determined to not have been a medical emergency. This is an attempt by state agencies to reduce “non-emergency” use of the ED.19 Another important issue is that 69% of Medicaid patients are in comprehensive managed care contracts.9,54 As of 2019, the lion’s share of these contracts were provided by 16 parent firms, 7 of which are publicly traded, for-profit firms.9 This level of consolidation and management by for-profit companies has the potential to negatively influence reimbursement trends for Medicaid as managed care firms seek to increase their profit. It is therefore important that emergency physicians are aware of trends affecting Medicaid reimbursement rates in their state as well as policies that might increase patients’ likelihood of cost sharing for ED care.

Privately insured patients have also faced many challenges of being billed for their ED visit after it was retrospectively deemed to be “not an emergency.” Some insurers have frequently denied claims for ED visits based on final diagnosis rather than the presenting complaint, which violates the “prudent layperson” standard (a requirement that insurers must pay for emergency services based on presenting symptoms (eg, chest pain) rather than the final determined diagnosis (eg myocardial infarction vs. musculoskeletal pain).46,47 In just one example, UnitedHealthcare announced a policy shift to “crack down” on non-emergent emergency room claims.48 This shift may influence patients to pause before seeking needed emergency care, which may result in more complex and expensive presentations of illness.

Cost sharing – regardless of insurance status – can have a direct impact on the care that we provide for patients in the emergency department. This can take the form of patients having fear about the cost of the ED before they seek care, hesitating to seek care, and then – if they do seek care – feeling hesitant to accept the recommendations made by their ED physician due to fear of cost. This presents a unique threat to the therapeutic alliance between patients and their physicians. Understanding how patients pay for health care matters to those providing it.

Moving Forward

Patients will continue to play a key role as “payers” of emergency care. Yet the degree to which they do so in such an expensive system, as well as confusion about what insurance protection actually means to their own pocketbooks, will continue to be the source of much policy debate.

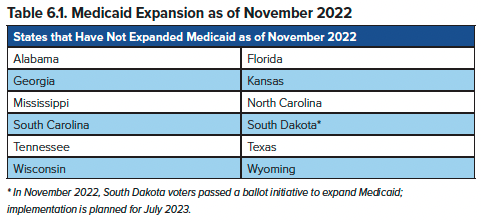

The substantial gains in health insurance coverage to millions of Americans since the ACA was signed into law have helped to reduce the likelihood that ED patients have no form of financial protection when receiving emergency care. These coverage gains are aligned with the American College of Emergency Physicians statement: “ACEP believes all Americans must have health care coverage.”52 However, coverage gains have been uneven. Specifically, millions of Americans would be eligible for Medicaid under federal law, but 12 states (listed below, as of November 2022) have not opted to expand coverage for a variety of reasons.53

Beyond advocacy for expanding insurance coverage, another area of advocacy related to patients as payers of ED care is the ongoing threats to the “prudent layperson” standard. ACEP and EMRA have a strong history of advocacy related to this topic. Private insurers such as UnitedHealthcare and Anthem have attempted to implement policies that shift emergency care reimbursements from “complaint-based” to “diagnosis-based.” When Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield, one of the nation’s largest private insurers, introduced these policy changes in 2017, ACEP alongside other physician groups sued them for violation of the prudent layperson standard as well as the Civil Rights Act.55,56 Ultimately, in 2022, the insurer discontinued their “avoidable ER” program and ACEP and the other groups settled and withdrew their lawsuit, having successfully protected the prudent layperson standard.

Another domain of ongoing policy interest and further advocacy are national and state initiatives designed to improve health care price transparency, thereby improving a patient’s ability to know how much something costs before they obtain care. For instance, the Fair Health Consumer Website serves as a resource for patients to look up the approximate cost of services at particular institutions and provide guidance on how to read one’s medical bill. CMS also recently implemented a new rule requiring all hospitals in the United States to list prices publicly for the most common services as of Jan. 1, 2021, but compliance with this new rule has been uneven.57 In June 2022, two Georgia hospitals were the first institutions to be fined under this new policy, owing over $1 million combined for price transparency violations.58 While these resources may be helpful for someone choosing a hospital for an elective procedure, it is doubtful that patients can or should shop for care while experiencing a medical emergency.

Taken together, the structure of the U.S. health system places patients in a challenging position as payers of health care. Patients are both uncertain exactly how much something costs or what they will be expected to pay out of pocket after an emergency happens. Innovations in insurance models and care delivery continue to promote the concept of patient as consumer, yet people are placed in a marketplace with little to no transparency, a complex bureaucracy and regulatory environment, and a constantly changing landscape. It is no surprise that some patients avoid seeking emergency care when they fear crippling medical expenses as a result. As emergency physicians, we play a critical role in advocating for policies that ensure that patients do not hesitate to seek emergency care for anything, anytime, and regardless of ability to pay.

TAKEAWAYS

- The U.S. health care system is both expensive and extremely complex, consisting of a patchwork of payers, physicians, and hospitals that can be confusing for patients to navigate.

- Patients are key payers of health care in the U.S. system.

- Since the passage of the ACA the number of uninsured Americans has dropped substantially

- Coverage gains due to the ACA have been uneven and incomplete especially due to incomplete expansion of Medicaid.

- Patients are worried about the cost of health care, including ED care, regardless of insurance status.

- Health care costs have the potential to impact the physician-patient therapeutic alliance as patients may be hesitant to receive recommended care due to fear of unknown costs.

- Safety-net and lifesaving emergency care in the ED is both legally required by EMTALA and medically necessary yet patients frequently face enormous cost-sharing burdens through various mechanisms such as “surprise bills,” lack of price transparency, narrow networks, and insurance company violations of the “prudent layperson” standard.

References

- American College of Emergency Physicians. EMTALA Fact Sheet. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Rice T, Rosenau P, Unruh LY, Barnes AJ, Saltman RB, van Ginneken E. United States of America: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2013;15(3):1-431.

- Institute of Medicine. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditure (NHE) Fact Sheet. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015. Health of the Healthcare System: An Overview. KFF. Published November 25, 2015. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Commonwealth Fund. International Health Care System Profiles. United States. Accessed May 10, 2022.

- Gonzalez Morganti K, Bauhoff S, Blanchard JC, et al. The Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States. RAND Corporation; 2013. Accessed January 5, 2021.

- Sawyer NT. Why the EMTALA Mandate for Emergency Care Does not Equal Healthcare “Coverage.” West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(4):551-552.

- Hinton E, Feb 23 LSP, 2022. 10 Things to Know About Medicaid Managed Care. KFF. Published February 23, 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022.

- Dieleman JL, Cao J, Chapin A, et al. US Health Care Spending by Payer and Health Condition, 1996-2016. JAMA. 2020;323(9):863-884.

- Lee A, Chu RC, Peters C, Sommers BD. Health Coverage Changes Under the Affordable Care Act: End of 2021 Update. Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Cha AE, Cohen RA. Demographic Variation in Health Insurance Coverage: United States, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics; 2022. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Adashi EY, O’Mahony DP, Cohen IG. The Affordable Care Act Resurrected: Curtailing the Ranks of the Uninsured. JAMA. Published online October 18, 2021.

- Zhou RA, Baicker K, Taubman S, Finkelstein AN. The Uninsured Do Not Use The Emergency Department More—They Use Other Care Less. Health Affairs. 2017;36(12):2115-2122.

- Anderson GF. From ‘Soak The Rich’ To ‘Soak The Poor’: Recent Trends In Hospital Pricing. Health Affairs. 2007;26(3):780-789.

- Muoio D. Hospitals often charge uninsured, cash-paying patients more than payers, WSJ reports. Fierce Healthcare. Published July 7, 2021. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Scott KW, Scott JW, Sabbatini AK, et al. Assessing Catastrophic Health Expenditures Among Uninsured People Who Seek Care in US Hospital-Based Emergency Departments. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(12):e214359.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021 Employer Health Benefits Survey - Section 7: Employee Cost Sharing. KFF. Published November 10, 2021. Accessed June 10, 2022.

- gov. Cost Sharing. Accessed June 12, 2022.

- Freed M, Damico A, 2022. Help with Medicare Premium and Cost-Sharing Assistance Varies by State. KFF. Published April 20, 2022. Accessed June 14, 2022.

- Artiga S, Ubri P, Zur J. The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings. KFF. Published June 1, 2017. Accessed June 15, 2022.

- Rae M, Copeland R, Cox C. Tracking the rise in premium contributions and cost-sharing for families with large employer coverage. Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. Published August 14, 2019. Accessed June 10, 2022.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Public Poll: Emergency Care Is The Most Essential Health Benefit To Cover. Published July 10, 2017. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Essential Health Benefits: HHS Informational Bulletin. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Kearney A, Hamel L, Stokes M, Brodie M. Americans’ Challenges with Health Care Costs. KFF. Published December 14, 2021. Accessed June 2, 2022.

- Ortaliza J, Fox L, Claxton G, Amin K. How does cost affect access to care? Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. Published January 14, 2022. Accessed June 10, 2022.

- Kliff S. Surprise Medical Bills, the High Cost of Emergency Department Care, and the Effects on Patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1457-1458.

- Kliff S. I read 1,182 emergency room bills this year. Here’s what I learned. Vox. Published December 18, 2018. Accessed February 13, 2019.

- Kennedy K, Johnson W, Biniek JF. Surprise out-of-network medical bills during in-network hospital admissions varied by state and medical specialty, 2016. Health Care Cost Institute. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Simon EL, de Moor C, Dayton J, Schmitz G. Insurance Companies Force Emergency Departments Out of Network, Shift Costs to Patients. ACEP Now. Accessed November 14, 2022.

- Sun EC, Mello MM, Moshfegh J, Baker LC. Assessment of Out-of-Network Billing for Privately Insured Patients Receiving Care in In-Network Hospitals. JAMA Int Med. 2019;179(11):1543-1550.

- Kliff S. ER doctors agree it’s time to tackle surprise emergency room bills. Vox. Accessed June 14, 2022.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. ACEP4U: Federal Surprise Billing Advocacy. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020. A Polling Surprise? Americans Rank Unexpected Medical Bills at the Top of Family Budget Worries. KFF. Published February 28, 2020. Accessed June 9, 2022.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. The No Surprises Act. Accessed June 14, 2022.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. No Surprises: Understand your rights against surprise medical bills | CMS. Accessed June 3, 2022.

- Scott JW, Raykar NP, Rose JA, et al. Cured into Destitution: Catastrophic Health Expenditure Risk Among Uninsured Trauma Patients in the United States. Ann Surg. 2018;267(6):1093-1099.

- Khera R, Hong JC, Saxena A, et al. Burden of Catastrophic Health Expenditures for Acute Myocardial Infarction and Stroke Among Uninsured in the United States. Circulation. 2018;137(4):408-410.

- Xu K, Evans DB, Carrin G, Aguilar-Rivera AM, Musgrove P, Evans T. Protecting Households From Catastrophic Health Spending. Health Affairs. 2007;26(4):972-983.

- Young G, Rae M, Claxton G, Wager E, Amin K. Many households do not have enough money to pay cost-sharing in typical private health plans. Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. Published March 10, 2022. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- Andalo P. Hit with $7,146 for two hospital bills, a family sought health care in Mexico. NPR. Published April 27, 2022. Accessed June 16, 2022.

- RAND Corporation. Analysis of High Deductible Health Plans. RAND Corporation Accessed June 10, 2022.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021 Employer Health Benefits Survey - Section 8: High-Deductible Health Plans with Savings Option. KFF. Published November 10, 2021. Accessed June 16, 2022.

- gov. High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP). HealthCare.gov. Accessed June 17, 2022.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Trends in the Utilization of Emergency Department Services, 2009-2018. 2021.

- American Academy of Emergency Medicine. Prudent Layperson Definition of Medical Emergencies. Published June 28, 2017. Accessed June 12, 2022.

- Tintinalli JE. Analysis of insurance payment denials using the prudent layperson standard. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(3):291-293, discussion 294.

- Henderson J. UnitedHealthcare to Crack Down on “Non-Emergent” ED Claims. Medpage Today. Published June 8, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022.

- Khullar D, Schpero WL, Bond AM, et al. Association Between Patient Social Risk and Physician Performance Scores in the First Year of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System. JAMA. 2020;324(10):975-983.

- Marcus A. How Social Drivers of Health Lead to Physician Burnout. Medscape. Published March 23, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- Glied SA, Remler DK, Springsteen M. Health Savings Accounts No Longer Promote Consumer Cost-Consciousness: Analysis examines whether health savings accounts promote consumer cost consciousness. Health Aff. 2022;41(6):814-820.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Health Care Reform. Accessed May 17, 2022.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map | KFF. Published June 15, 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022.

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Managed Care. MACPAC. Accessed June 15, 2022.

- Livingston S. Hospitals and patients feel the pain from Anthem’s ED policy. Modern Healthcare. Published December 2, 2017. Accessed June 14, 2022.

- Physician Groups Take Legal Action Against Anthem’s Blue Cross Blue Shield of Georgia. Published July 17, 2018. Accessed June 15, 2022.

- Borden W. Only 14% of hospitals comply with federal price transparency rules, advocacy group finds. Healthcare Dive. Published February 11, 2022. Accessed June 11, 2022.

- Aiken-Shaban N, Pighini E. CMS levies penalties for non-compliance with Hospital Price Transparency Rule. Health Industry Washington Watch. Published June 21, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2022.