Ch. 10 - Chronic Pain & Substance Use Disorder

David H. Cisewski, MD, MS | Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Reuben J. Strayer, MD | Maimonides Medical Center

In recent years, emergency providers have witnessed an exponential rise in both prescription and illicitly obtained opioid abuse across the country. Despite false claims widely promulgated in the 1990s and 2000s regarding opioid safety, it is now clear that even a short course of opioids may lead to long-term use and addiction.1 This increased opioid utilization has led to a current opioid use disorder (OUD) epidemic that has affected an estimated 3 million individuals in the United States,2 with drug overdose deaths surpassing 70,000 people nationally in 2018.3 As the emergency department is often the primary point of medical access for many patients with OUD suffering from a variety of painful conditions, emergency providers are uniquely positioned to optimize their care. The purpose of this chapter is to provide evidence-based recommendations on how to safely and effectively manage pain in patients being harmed – or at risk of being harmed – by opioid dependence or addiction in the emergency setting.

CHRONIC PAIN

Among patients with chronic, non-cancer pain it is important to note that although the pain being experienced may have initially resulted from an acute injury, the resulting chronic pain is typically pathologic, secondary to an upregulation of pain signaling receptors, and associated with hypersensitivity to stimuli.4 As a result, these pain presentations are managed differently from acute injury/illness. When an acute flare of a chronic pain condition peaks, patients may seek assistance in the emergency setting due to delays in evaluation with their primary providers or a lack of outpatient management services. Patients who present to the ED with an exacerbation of chronic pain should be educated as to the harms – and lack of functional benefit – associated with continued opioid use. Demonstrating a willingness to listen to the patient’s concerns and initiating a discussion with their primary pain providers (or initiating such services if they do not yet exist) is optimal care. Explain the benefits of non-pharmacologic alternatives such as exercise, acupuncture, mindfulness, or massage for their underlying chronic pain condition. Although expediency suggests a short-course of opioids may assist in breakthrough pain, this strategy is more likely to initiate or perpetuate the cycle of chronic pain and opioid use that leads to declining functional status. Patients with chronic pain are more likely to be harmed than benefited by opioid therapy.5-8

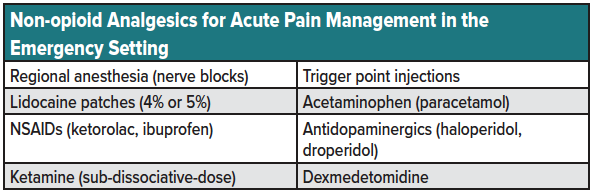

Many patients with chronic pain use daily opioids prescribed by their pain providers. Such pain management programs are ideally tailored to specific functional goals and structured around a patient-provider agreement; maintaining a single opioid prescriber is essential. ACEP guidelines specify that acute care providers managing patients with chronic pain should avoid administering opioids or altering existing opioid regimens.9,10 Additionally, both ACEP and AAEM recommend against filling lost or stolen prescriptions or refilling lapsed prescriptions for patients with chronic pain presenting to the ED. Instead, encourage these patients to follow up with their provider as soon as possible and attempt to communicate with their provider to ensure early follow-up. Analgesic therapy may be used to bridge these patients to their next appointment but should consist of a combination of non-pharmacologic and non-opioid analgesic modalities (see table 1 for a list of non-opioid analgesics for acute pain management in the emergency setting).

[Note: the treatment recommendations above for acute exacerbations of chronic pain do not apply to hospice or palliative patients among whom the benefits of pain alleviation outweigh the risks of tolerance and addiction.]

ACUTE PAIN IN PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC PAIN OR PATIENTS BEING TREATED FOR OUD

Some patients with chronic pain frequently seek care for exacerbations of their chronic pain. However, the emergency clinician attending to such a patient must be wary of anchoring bias and consider new (possibly dangerous) pathologies that may have led to the present visit.

Patients with a history of OUD who are in medication or abstinence-based recovery may also present with acute pain from illness or injury. These patients require a multimodal analgesic approach similar to all ED patients; however, patients in abstinence-based recovery (i.e., former daily opioid users who are now not using opioids and not being treated in a medication-assisted treatment (MAT) program) are at particular risk to being harmed by exposure to opioids, which could trigger a relapse to misuse and long-term use. Nevertheless, it is important to avoid undertreatment of pain, as both poorly controlled pain,11 and trauma-related stress and anxiety, may precipitate relapse in this group.12 If pain cannot be controlled with non-opioid alternatives, a short course of less euphoric opioids (morphine favored over hydromorphone, hydrocodone, and oxycodone) may be utilized for analgesic relief.13 The decision to use opioids to treat OUD patients in abstinence recovery should be part of a shared decision-making conversation with the patient, focusing on the harms and benefits of opioid use. Empowering the patient to manage their own analgesic regimen may assist in the over-utilization of unneeded opioids.

Among patients with a history of OUD not on MAT, a multimodal approach involving non-opioid and non-pharmacologic analgesic alternatives is favored as first-line treatment. Examples of non-opioid analgesic alternatives include regional anesthesia (nerve blocks), trigger point injections, lidocaine patches (4% or 5%), acetaminophen, NSAIDs (ketorolac, ibuprofen), antidopaminergics (haloperidol, droperidol), sub-dissociative ketamine, and sub-anesthetic dose propofol for migraines (see table).

Among patients with OUD being treated with buprenorphine or methadone, a multimodal approach involving non-opioid analgesic alternatives is still the favored first-line regimen. Additionally, for patients on buprenorphine, the analgesic effect of buprenorphine can be augmented by dividing the patient’s daily dose of buprenorphine into smaller, more frequent doses (e.g., every 6-8 hours).6,7 Patients on buprenorphine maintenance will be resistant to full agonist opioids (e.g., morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, methadone) and patients on methadone maintenance have a narrow therapeutic window for analgesia. They may require high doses of conventional opioids, putting them at risk of opioid toxicity. Patients on MAT admitted to the hospital with ongoing acute pain should have their MAT regimen continued and managed in collaboration with their MAT provider.

CONCLUSION

Although emergency providers routinely treat pain in opioid-naïve patients, the safe and effective management of pain in patients with chronic pain or a history of OUD presents a variety of distinct challenges. Because the emergency department is where many in this group seek medical care, emergency providers are uniquely positioned to optimize their safe and effective pain management. A full consideration of non-opioid and non-pharmacologic analgesic alternatives is essential to avoiding exposure to the harms of continued high-risk opioid use.

References

- Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of Initial Prescription Episodes and Likelihood of Long-Term Opioid Use - United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:265-9.

- Soyka M. New developments in the management of opioid dependence: focus on sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2015;6:1-14.

- Ahmad F, Rossen L, Spencer M, Warner M, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. In: Statistics NCfH, editor.: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018.

- Dinakar P, Stillman AM. Pathogenesis of Pain. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2016;23:201-8.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

- Juurlink DN, Dhalla IA. Dependence and addiction during chronic opioid therapy. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8:393-9.

- Manchikanti L, Datta S, Derby R, et al. A critical review of the American Pain Society clinical practice guidelines for interventional techniques: part 1. Diagnostic interventions. Pain Physician. 2010;13:E141-74.

- Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic non-cancer pain. CMAJ. 2017;189:E659-E66.

- Motov S, Strayer R, Hayes BD, et al. The Treatment of Acute Pain in the Emergency Department: A White Paper Position Statement Prepared for the American Academy of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med. 2018;54:731-6.

- Cantrill SV, Brown MD, Carlisle RJ, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the prescribing of opioids for adult patients in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:499-525.

- Larson MJ, Paasche-Orlow M, Cheng DM, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Saitz R, Samet JH. Persistent pain is associated with substance use after detoxification: a prospective cohort analysis. Addiction. 2007;102:752-60.

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:363-71.

- Ward EN, Quaye AN, Wilens TE. Opioid Use Disorders: Perioperative Management of a Special Population. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:539-47.