Ch. 4 - Abdominal Pain

Raymond Isenburg, DO | St. Joseph's University Medical Center

Alexis M. LaPietra, DO | St. Joseph' University Medical Center

Abdominal pain is one of the most common chief complaints among patients in the emergency department, comprising approximately 5% of all ED visits.1 Abdominal pain provides unique diagnostic and pain management challenges, as the severity of illness may be unrelated to the degree of pain.

A definitive diagnosis can also be difficult, with up to 25% of all abdominal pain evaluated in the ED receiving a diagnosis of "undifferentiated" abdominal pain.1 The pathology encompassing abdominal pain is vast and ranges from mild, transient conditions to severe, life-threatening abdominal catastrophes.

Similar to many pain presentations, abdominal pain is a symptom, not a diagnosis – pain may diminish with effective treatment, but identification of the underlying source and ruling out of life-threatening pathology is essential. An over-reliance on physical exam findings, vital signs, or lab tests can often lead to missed diagnoses.1 Serious diagnoses must be considered, including, but not limited to, appendicitis, cholecystitis, pyelonephritis, pancreatitis, bowel obstruction or malrotation, diverticulitis/colitis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, ovarian or testicular torsion, ectopic (ruptured or unruptured) pregnancy, atypical acute coronary syndrome, diabetic or alcoholic ketoacidosis, and mesenteric ischemia. A woman of childbearing age with acute abdominal pain should be considered pregnant until proven otherwise.

History and Physical of Abdominal Pain

A thorough history and physical is of the utmost importance when assessing abdominal pain. The location, onset, severity, provoking features, and associated symptoms can assist emergency physicians in better understanding the pathophysiology behind the pain. Asking about medications taken before arrival – what, when, the quantity taken - will also play a role in determining what analgesic option is the most appropriate for use in the ED. Association with food or defection, last bowel movement, last menstrual period and current sexual activity, prior surgical procedures, and passage of gas are essential components of history that can aid in focusing the differential diagnosis.

The presence or absence of fever, tachycardia, and hypotension are essential clues to the severity and etiology of the pain. For example, hypotension and relative bradycardia should raise a red flag for the parasympathetic reflex seen in ectopic pregnancy rupture or free fluid in the abdomen.2 However, research has shown that vital signs are a poor correlator to pain and that patients in severe pain can present with otherwise normal vital signs.3,4 The patient description of pain severity should still be considered the gold standard. Additionally, diligence and high suspicion of dangerous etiologies are required among older patients, patients with prior abdominal surgeries, psychiatric patients, and women of reproductive age who have an increased pretest probability of surgical pathology.

Treatment of Mild to Moderate Abdominal Pain

Despite the broad differential diagnosis for abdominal pain, management is relatively universal. General concepts for the treatment of abdominal pain include a multi-modal analgesic approach with judicious and responsible use of opioid agents for moderate to severe pain. Ultimately, the analgesic regimen should depend on the suspected source of pain, clinician’s preference, and departmental protocols.

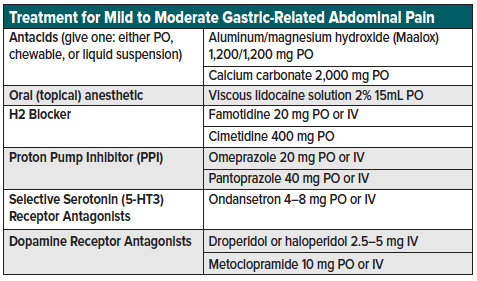

For patients suspected of benign, gastric-related pain (peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, gastroesophageal reflux) who are tolerating oral medications, consider the following oral and parenteral regimen:

- “GI cocktail” combination of viscous lidocaine, H2-blockers or proton pump inhibitors (PPI), and antacids (Maalox, calcium carbonate).

- Oral ondansetron or metoclopramide may also be added if nausea continues despite the first-line “GI cocktail”

- Parenteral antiemetics may be added for patients experiencing nausea or vomiting (droperidol5–5 mg IV, ondansetron 4–8 mg IV, metoclopramide 10 mg IV)

- Agents may take 30-60 minutes to take effect; re-evaluate frequently

- Take caution with using NSAIDs which may exacerbate the underlying abdominal pathology

- See table 1 for a list of gastric pain analgesic options

Treatment of Moderate to Severe Abdominal Pain

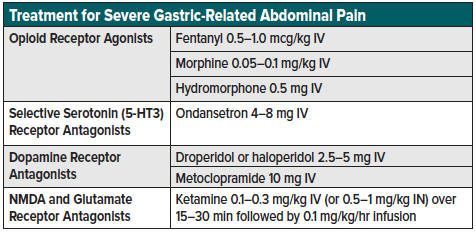

For patients with undifferentiated abdominal pain and a moderate to high suspicion for hepatobiliary, pancreatic, intestinal, or vascular pathology, consider advancing the analgesic regimen with the following additional recommendations:

- A multi-modal analgesic regimen utilizing options with different mechanisms can assist in a multi-targeted receptor approach that optimizes the safety and efficacy of each individual pharmacologic agent

- For patients presenting with severe pain or concern for surgical pathology, consider beginning parenteral opioids early in the treatment course.

- For hypotensive patients consider ketamine as a hemodynamically neutral agent

- Utilize adjunct antiemetics with the analgesic regimen to decrease overall pain and discomfort

- Opioids given in multiple doses may contribute to increased nausea/vomiting. Patients on daily opioids still can benefit from non-opioid analgesics such as IV sub-dissociative dose ketamine and can receive immediate-release opioids for the break-through pain

- See table 2 for a list of treatment options for moderate to severe abdominal pain

In patients with severe abdominal pain concerning for surgical pathology, opioids should be considered as a rapid means of treating severe, undifferentiated pain. Despite the historical misconception that analgesia interferes with the surgical evaluation of the acute abdomen,5 research has shown that analgesia does not increase the risk of diagnosis error or the risk of failure in assessing these patients.6

When appropriate, a non-opioid analgesic regimen may be used as a first-line therapy to treat underlying causes of abdominal pain while reserving opioids for severe breakthrough pain. Alternatives to opioids, NSAIDs, ketamine, inhaled nitrous oxide, topical analgesics (capsaicin), dopamine receptor antagonists. Nerve blocks are also received increased recognition as an analgesic modality for a variety of abdominal pain presentations.7

NSAIDs

NSAIDs (ketorolac, ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac) are reversible COX-1,2 inhibitors that function as analgesics, antipyretics, and anti-inflammatory agents and, along with acetaminophen, are considered first-line treatment for presentations of mild to severe acute pain.8-10 Ketorolac is a commonly used NSAID, and research suggests 10 mg IV ketorolac is the analgesic ceiling for acute pain management in the emergency department, with higher dosing resulting in similar rates of adverse effects such as dizziness, nausea, and headache without an increased analgesic contribution.11 However, NSAIDs are contraindicated in patients with renal disease, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, heart failure, and third trimester pregnancy12-14 as well as cirrhotic patients in which renal perfusion is reliant on prostaglandin synthesis to prevent the progression of hepatorenal syndrome.15 Additionally, NSAIDs should be used cautiously in elderly patients with cardiovascular comorbidities, volume depletion, pre-existing renal or liver disease, or loop diuretic use as these place patients at a higher risk of drug-induced acute renal failure.16-18 As a result, NSAIDs are generally not considered first-line treatment for abdominal pain (excluding renal colic and probably biliary colic).

Dopamine Receptor Antagonists/Antiemetics

Beyond dopamine’s role in motivational behavior, it is also involved in the pain propagation where inhibition may prevent signal propagation and reducing pain signaling.19 Metoclopramide (10-20 mg IV) is the classic dopamine receptor antagonist used to relieve nausea and vomiting, which research has shown to be more distressing than pain in the emergency setting.20 However, many researchers question the efficacy of antiemetics over placebo,21,22 supported by the results of a Cochrane Review that found no definite evidence to support the superiority of any particular antiemetic drug over placebo.23 Utilization of antiemetics should be used per provider discretion as a complement to – and not the sole treatment – in patients being treated for acute abdominal pain in the emergency setting.

Ketamine

Ketamine is an NMDA and glutamate receptor antagonist traditionally used for procedural sedation, though found to be an effective analgesic when used at lower (subdissociative) doses (SDK).32 Ketamine at doses of 0.1-0.3 mg/kg IV can be as an adjunct to opioids or as an opioid alternative. Among patients with abdominal pain who present hypotensive, ketamine may be considered to an opioid alternative.33-35 To avoid psycho-perceptual side effects, ketamine should be given slowly over 15-30 minutes.36 Patients requiring repeat doses of ketamine may benefit from a continuous infusion (0.1–0.15 mg/kg/hr) and titrate to effect.

Evolving Analgesics Treatment

Nerve Blocks

The transversus abdominis plane or “TAP” block is an ultrasound-guided plane block providing analgesia to the anterior abdominal wall via delivery of local anesthetic between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. Research has shown analgesic efficacy for intestinal wall pathologies such as abscesses, hematomas, surgical wounds, and inguinal hernia.37 However, recent literature has suggested an abdominal fascial plane nerve block may be an effective adjunctive for acute abdominal pain.7 At this time, more research is needed to support the safety and efficacy of this analgesic technique in the emergency setting. (see nerve block chapter for further discussion).

Lidocaine

Lidocaine is the voltage-dependent sodium channel blocking agent commonly used as an anesthetic in the emergency setting. However, when administered intravenously, lidocaine (1.5 mg/kg IV) has been shown to offer quick onset and an extended duration of analgesic relief.38-40 IV lidocaine may be considered an effective analgesic adjunct to opioids or an analgesic alternative when NSAIDs are contraindicated. However, as a stand-alone agent, IV lidocaine was found to be inferior to IV opioids (hydromorphone) in treating generalized abdominal pain in the emergency setting.41 A recent systematic review found no definitive evidence to recommend or discourage IV lidocaine use, noting “further research is needed to assess the efficacy and safety of IV lidocaine for specific pain pathologies in the emergency setting.” 42

Nil Per Os (NPO) Status in Patient with Abdominal Pain

Significant debate has revolved around withholding food and liquid in patients presenting to the emergency department with undifferentiated abdominal pain.43,44 Traditional teaching has been NPO at midnight for any patient suspected or confirmed surgical pathology. However, withholding food and drink has been shown to worsen pain and discomfort during ED stay and evaluation. 43,44 It is worth highlighting that the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) 2015 Guidelines indicate a “2-4-6-8” hour minimum fasting period. Specifically, 2 hours for clear liquids (water, juice without pulp, carbonated beverages, black coffee, tea); 4 hours for breast milk; 6 hours for a light meal consisting of toast and clear liquids; and 8 hours for solid and fatty meals.45 Adherence to these guidelines while allowing patients to eat or drink outside these windows has been shown to reduce patient and provider dissatisfaction without resulting in an increased risk of adverse events44,46,47. Additionally, this approach may improve postoperative recovery by avoiding a catabolic state.48 Providers should take these cutoffs into consideration, and when clear liquids or juices would improve patient pain and discomfort, they should be safely allowed.43

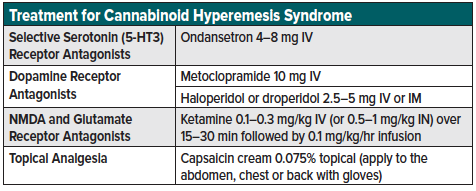

Special Considerations: Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) refers to a clinical syndrome of intractable nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain in a regular cannabis user. CHS is often refractory to traditional antiemetic therapies, requiring ED presentation for further treatment. Patients will classically describe the alleviation of abdominal pain only with hot showers.

From a pharmacologic perspective, topical capsaicin, parenteral ketamine, and the dopamine antagonists (haloperidol) have shown to be efficacious in the emergency setting. Haloperidol and droperidol are first-generation antipsychotics that achieve their analgesic effect through dopamine receptor blockade (D2-R antagonist).24 Though typically used for psychosis and agitation, research has shown analgesic efficacy for sub-classes of abdominal pain such as gastroparesis and cannabinoid-induced hyperemesis syndrome.25-28 Haloperidol and droperidol can be administered IV or IM with a starting dose of 2-5 mg IV or IM, with repeat dosing at 30 minutes if needed.28,29 Optimal use involves a “start low, go slow” approach to obtain the lowest possible therapeutic dose while avoiding cardiac toxicity.28,29 Haloperidol should be used cautiously as it can cause extrapyramidal symptoms and QT prolongation, and an increased risk of torsades de pointes/sudden cardiac death.30,31 See table 3 for a list of treatment options for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.

Note: Although haloperidol administered intravenously has been shown to treat abdominal pain effectively, it is FDA-approved for oral and intramuscular routes, and IV administration remains off-label.

Disposition and Discharge Analgesic Options

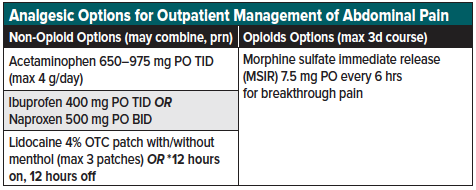

For patients with unremitting pain or surgical pathology, admission may be necessary for further treatment and analgesic management. For stable/improving patients who may be discharged safely, provide close return precautions and a multi-modal pain management regimen of non-opioids and opioids for breakthrough pain only. If opioids are necessary upon discharge, it is recommended to provide the lowest effective dose for the fewest number of days with strict instructions regarding abuse/misuse, safe storage/disposal, and timely follow-up.49 Patients should be encouraged to use scheduled non-opioid medications while awake, reserving opioids only as needed for severe breakthrough pain. Avoiding opioid/APAP or opioid/ibuprofen combinations allows patients to take a full analgesic dose of the non-opioid portion, which may provide better overall relief than the sub-analgesic doses in the combination opioid tablets. Morphine sulfate immediate release (MSIR) is equally efficacious in terms of pain relief but without the same likability (i.e., abuse potential) as compared to oxycodone.50,51 Dysphoria and an increased negative side effect profile, when taken at supratherapeutic doses, are known adverse effects of oral MSIR.52,53 [Recommended guideline: 3-day supply of MSIR 7.5 mg q6hrs with a plan for reevaluation if pain persists beyond three days.] If a patient is discharged with combination opioid tablets, education on the total daily milligrams recommended of the non-opioid agent (i.e., APAP 4 g/day) is important to avoid toxicity.

Always document a reassessment of physical exam and patient subjective symptoms prior to discharge. While the ultimate goal of pain management is to improve the quality of life by returning the patient to their baseline functional status, elimination of pain may not be feasible. The goal is not zero pain, but enough reduction to allow the patient to continue their daily activities during a painful condition.54 Among patients being discharged with an undifferenced diagnosis (“abdominal pain, unspecified”) it is essential to explain to the patient that any change in symptoms, acute worsening in abdominal pain, or an inability to tolerate oral foods or medications should prompt immediate return to the emergency department. See table 4 for a list of analgesic options for outpatient management of abdominal pain.

Summary

Despite the common presentation and a wide range of potential diagnoses of abdominal pain, a large percentage of the presentation will go “undifferentiated” at discharge. A full consideration of the life-threatening diagnoses should be considered regardless of vital signs, lab results, or subjective symptoms. For mild to moderate pain, an oral analgesic regimen, including a “GI cocktail” should be considered. Among patients with more concerning severe abdominal pain in which surgical pathology is found, patients should be placed on a multi-modal parenteral analgesic regimen. Patients with improvement in symptoms may be discharged with close, explicit return precautions and a short course of an outpatient oral analgesic regimen.

References

- Kamin RA, et al., Pearls and pitfalls in the emergency department evaluation of abdominal pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003. 21(1):61-72, vi.

- Snyder HS. Lack of a tachycardic response to hypotension with ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Am J Emerg Med. 1990. 8(1):23-6.

- Lord B, Woollard M. The reliability of vital signs in estimating pain severity among adult patients treated by paramedics. Emerg Med J. 2011. 28(2):147-50.

- Block PR, et al. Pain Catastrophizing, rather than Vital Signs, Associated with Pain Intensity in Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department for Pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2017. 18(2):102-109.

- Cope Z. Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen, 2nd, Oxford, London 1921.

- Manterola C, et al. Analgesia in patients with acute abdominal pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(1):CD005660.

- Mahmoud S, et al. Ultrasound-guided transverse abdominis plane block for ED appendicitis pain control. Am J Emerg Med. 2019. 37(4): p. 740-743.

- Laska EM, et al. The correlation between blood levels of ibuprofen and clinical analgesic response. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986. 40(1):1-7.

- Seymour RA, Ward-Booth P, Kelly PJ. Evaluation of different doses of soluble ibuprofen and ibuprofen tablets in postoperative dental pain. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;34(1):110-4.

- Chang AK, et al. Effect of a Single Dose of Oral Opioid and Nonopioid Analgesics on Acute Extremity Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661-1667.

- Motov S, et al. Comparison of Intravenous Ketorolac at Three Single-Dose Regimens for Treating Acute Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(2):177-184.

- American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Group on Use of, S. and D. Nonselective Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory, Recommendations for use of selective and nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: an American College of Rheumatology white paper. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(8):1058-73.

- Feenstra J, et al. Association of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with first occurrence of heart failure and with relapsing heart failure: the Rotterdam Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(3):265-70.

- Danelich IM, et al. Safety of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with cardiovascular disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(5):520-35.

- Chandok N, Watt KD. Pain management in the cirrhotic patient: the clinical challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(5):451-8.

- Crome P. What’s different about older people. Toxicology. 2003;192(1):49-54.

- Grandison MK, Boudinot FT. Age-related changes in protein binding of drugs: implications for therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;38(3):271-90.

- Zeeh J, Platt D. The aging liver: structural and functional changes and their consequences for drug treatment in old age. Gerontology. 2002;48(3):121-7.

- Wood PB. Role of central dopamine in pain and analgesia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(5):781-97.

- Singer AJ, Garra G, Thode Jr HC. Do emergency department patients with nausea and vomiting desire, request, or receive antiemetics. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(5):790-791.

- Egerton-Warburton D, et al. Antiemetic use for nausea and vomiting in adult emergency department patients: randomized controlled trial comparing ondansetron, metoclopramide, and placebo. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(5):526-532 e1.

- Furyk JS, et al. Oligo-evidence for antiemetic efficacy in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(6):921-922.

- Furyk JS, Meek RA, Egerton-Warburton D. Drugs for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in adults in the emergency department setting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(9):CD010106.

- Honkaniemi J, et al. Haloperidol in the acute treatment of migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache. 2006;46(5):781-7.

- Jones JL, Abernathy KE. Successful Treatment of Suspected Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome Using Haloperidol in the Outpatient Setting. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016:3614053.

- Roldan CJ, et al. Randomized Controlled Double-blind Trial Comparing Haloperidol Combined With Conventional Therapy to Conventional Therapy Alone in Patients With Symptomatic Gastroparesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(11):1307-1314.

- Blumentrath CG, Dohrmann B, Ewald N. Cannabinoid hyperemesis and the cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults: recognition, diagnosis, acute and long-term treatment. Ger Med Sci. 2017;15:Doc06.

- Ramirez R, et al. Haloperidol undermining gastroparesis symptoms (HUGS) in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(8):1118-1120.

- Buttner M, et al. Is low-dose haloperidol a useful antiemetic?: A meta-analysis of published and unpublished randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2004;101(6):1454-63.

- Kurz M, et al. Extrapyramidal side effects of clozapine and haloperidol. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1995;118(1): 52-6.

- Meyer-Massetti C, et al. The FDA extended warning for intravenous haloperidol and torsades de pointes: how should institutions respond? J Hosp Med. 2010;5(4):E8-16.

- Motov S, et al. Is There a Role for Intravenous Subdissociative-Dose Ketamine Administered as an Adjunct to Opioids or as a Single Agent for Acute Pain Management in the Emergency Department? J Emerg Med. 2016;51(6):752-757.

- Mayer DJ, Price DD. Central nervous system mechanisms of analgesia. Pain. 1976;2(4):379-404.

- Wood JD, Galligan JJ. Function of opioids in the enteric nervous system. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16 Suppl 2:17-28.

- Holzer P. Opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. Regul Pept. 2009;155(1-3):11-17.

- Motov S, et al. A prospective randomized, double-dummy trial comparing IV push low dose ketamine to short infusion of low dose ketamine for treatment of pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(8):1095-1100.

- Herring AA, Stone MB, Nagdev AD. Ultrasound-guided abdominal wall nerve blocks in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(5):759-64.

- Soleimanpour H, et al. Parenteral lidocaine for treatment of intractable renal colic: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:256.

- Golzari SE, et al. Lidocaine and pain management in the emergency department: a review article. Anesth Pain Med. 2014;4(1):e15444.

- Firouzian A, et al. Does lidocaine as an adjuvant to morphine improve pain relief in patients presenting to the ED with acute renal colic? A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(3): 443-8.

- Chinn E, et al. Randomized Trial of Intravenous Lidocaine Versus Hydromorphone for Acute Abdominal Pain in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74(2):233-240.

- Silva LOJ, Scherber K, Cabrera D, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Intravenous Lidocaine for Pain Management in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(2): 135-144 e3.

- Ljungqvist O, Soreide E. Preoperative fasting. Br J Surg. 2003;90(4):400-6.

- Denton TD. Southern Hospitality: How We Changed the NPO Practice in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Nurs. 2015;41(4):317-22.

- Practice Guidelines for Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration: Application to Healthy Patients Undergoing Elective Procedures: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(3):376-393.

- Agarwal A, Chari P, Singh H. Fluid deprivation before operation. The effect of a small drink. Anaesthesia. 1989;44(8):632-4.

- Gilbert SS, Easy WR, Fitch WW. The effect of pre-operative oral fluids on morbidity following anaesthesia for minor surgery. Anaesthesia. 1995;50(1):79-81.

- Ljungqvist O. Preoperative carbohydrate loading in contrast to fasting. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2010;122(1-2): 6-7.

- Motov S. The Treatment of Acute Pain in the Emergency Department: A White Paper Position Statement Prepared for the American Academy of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med. 2018;54(5):731-736.

- Zacny JP, Lichtor SA. Within-subject comparison of the psychopharmacological profiles of oral oxycodone and oral morphine in non-drug-abusing volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2008;196(1):105-16.

- Wightman R, et al. Likeability and abuse liability of commonly prescribed opioids. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(4):335-40.

- Zacny JP. Differential effects of morphine and codeine on pupil size: dosing issues. Anesth Analg. 2005;100(2):598; author reply 598.

- Motov S, Strayer R, Hayes B, Reiter M, Rosenbaum S, Repanshek Z, Taylor S, Friedman B. AAEM White Paper on Acute Pain Management in the Emergency Department. 2017.

- Lee TH. Zero Pain Is Not the Goal. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1575-7.