Ch. 14 - Pain in Pregnancy

Rachel E. Bridwell, MD | Brooke Army Medical Center

Alex Koyfman, MD | UT Southwestern Medical Center

Brit Long, MD, FACEP | San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium

Pain is a common complaint in pregnancy, with as high as 57% of pregnant patients in the U.S. reporting at least one emergency department (ED) visit for a pain-related complaint 1 A similar finding is seen in Germany, with pain accounting for 28% of all pregnancy visits to the ED.2

Headaches, back pain, and abdominal/pelvic pain are the most common presenting pregnancy-related pain complaints in the emergency setting, and under 15% of pregnant women receive opioid prescriptions for these pregnancy-related complaints at some point during their pregnancy.3 Given the frequency of these presentations, a concern for opioid-overuse, and the additional concern for fetal safety, it is essential that emergency providers be adept at managing pain in this unique population.

Recognition and Assessment of Common Pain Presentations

Before considering the more common (benign) causes of pain, it is essential to consider the can't-miss diagnoses that often masquerade during pregnancy. Example include:

- Headache: subarachnoid hemorrhage, HELLP, preeclampsia/eclampsia, acute angle-closure glaucoma, carbon monoxide toxicity, temporal arteritis, cervical artery dissection, cerebral venous thrombosis, meningitis/encephalitis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH)

- Back pain: cauda equina syndrome, abdominal aortic aneurysm, spinal epidural abscess or osteomyelitis, spinal fracture (traumatic or pathologic, malignancy (tumor)

- Abdominal/pelvic pain: HELLP Syndrome, pyelonephritis, appendicitis, atypical ACS, placental abruption or uterine rupture, fetal demise/miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, active labor, bowel obstruction

- Traumatic pain: pain secondary to trauma, motor vehicle collision, or falls warrants a full trauma screening and evaluation; domestic violence should always be considered in a traumatic pregnancy evaluation

Once the life-threatening causes have been thoroughly considered and ruled out, efforts can focus on treating the underlying cause of pain.

Headaches: Headaches are frequent during pregnancy and most notable in the first trimester. Whereas a history of similar headaches may provide reassurance, new-onset headaches during pregnancy (particularly at >20 weeks' gestation) should raise a red flag. Particular attention should be given to headaches unresponsive to analgesia prior to ED arrival. A full assessment of visual acuity, vital signs, and basic labs should be conducted for further assessment. A lumbar puncture may also be warranted.

Back pain: Occurring in half of all pregnancies, low back pain is common and the result of regular physiologic changes of pregnancy, secondary to growth of the gravid uterus and subsequent lumbar lordosis. In combination with the release of increased relaxin, which causes ligamentous laxity, the increased mechanical and gravitational load placed on the paraspinal muscle beds adds to the stress to the lower lumbar spine.4 Radicular symptoms may be present as the gravid uterus compresses spinal roots. Evaluation is generally elicited through history and examination with symptom relief with heat, mechanical offloading, and massage and avoiding aggravation with axial loading. Careful evaluation should be directed at both evaluations for cauda equina syndrome, as well as sacroiliitis, highlighted by unilateral low lateral spinous pain.5 While MRI is considered safe during pregnancy, there are currently no studies to evaluate long term effects of ferromagnetic exposure on a fetus, and thus imaging should be conducted with extreme caution.4

Abdominal/pelvic pain: Abdominal pain is a common symptom during mid to late pregnancy. Fetal growth and round ligament stretching are associated with the sensation of contractions and self-resolving pain. However, moderate to severe pain associated with fever, vital sign abnormalities (tachycardia, hypotension, respiratory distress), syncopal episodes, or vaginal bleeding warrants further consideration of the previously listed life-threatening causes.

Neuropathic pain secondary to abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES) may occur during pregnancy as cutaneous branches of intercostal nerves at the lateral edge between the internal oblique rectus abdominus are compressed in the fibrous ring as they reach the dermis. ACNES-related pain is worsened by the stretching of the abdominal wall as the uterus grows.6,7 Patients with ACNES may have a positive Carnett's Sign, or pain further exacerbated by Valsalva or contracting the abdominal wall musculature.5 The difficulty in the examination is identifying tenderness within the cutaneous nerves versus visceral structures deep to the abdominal wall. Along with non-pharmacologic treatments, anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome responds well to ultrasound-guided transversus abdominus or rectus sheath blocks, providing both important diagnostic information as well as rapid therapeutic relief.7–9

Similar to ACNES, meralgia paresthetica occurs when the lateral cutaneous femoral nerve is entrapped between the tensor fascia lata and the inguinal ligament. Nerve compression results in a burning sensation on the lateral thigh, exacerbated by prolonged sitting or lateral recumbent position, resulting in sensory changes but the preservation of motor function. Symptoms abate after delivery of the fetus, though stretching or lying flat may alleviate pain. If refractory to stretching, a local nerve block with anesthetic and steroid may provide relief.10

Pharmacologic Options and Routes of Administration

While treating acute pain of pregnant patients in the ED presents the additional challenge of considering an analgesic regimen that is safe for fetal development, there remain multiple opioid and non-opioid pharmacologic treatments to choose from.

Mild/moderate pain: The mainstay of treatment is often acetaminophen (paracetamol, APAP), which is safe in all trimesters of pregnancy.11 Acetaminophen 325 to 1,000 mg PO every 4 to 6 hours (maximum 4 g/day) is considered a safe dosing regimen. A short course of NSAIDs may be considered a viable option during the first trimester. However, NSAIDs should be avoided in the second and third trimesters due to the risk of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus and risk of peripartum hemorrhage.11,12 Ibuprofen 400 mg PO (q4-6hrs) is the analgesic ceiling for short-term pain relief among adults presenting to the ED with acute pain.54 (See the musculoskeletal pain chapter for the full list of NSAID alternatives). For musculoskeletal pain, diclofenac gel may also present a localized option that provides relief to the mother without increased teratogenicity or spontaneous abortion risks.13

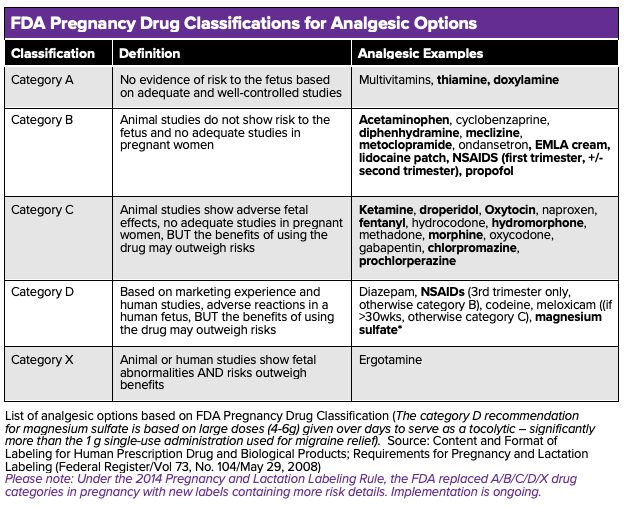

See table 1 for a list of different analgesic options based on their FDA classification. Note – although NSAIDs should be avoided during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, they are safe during breastfeeding and the first trimester of pregnancy.

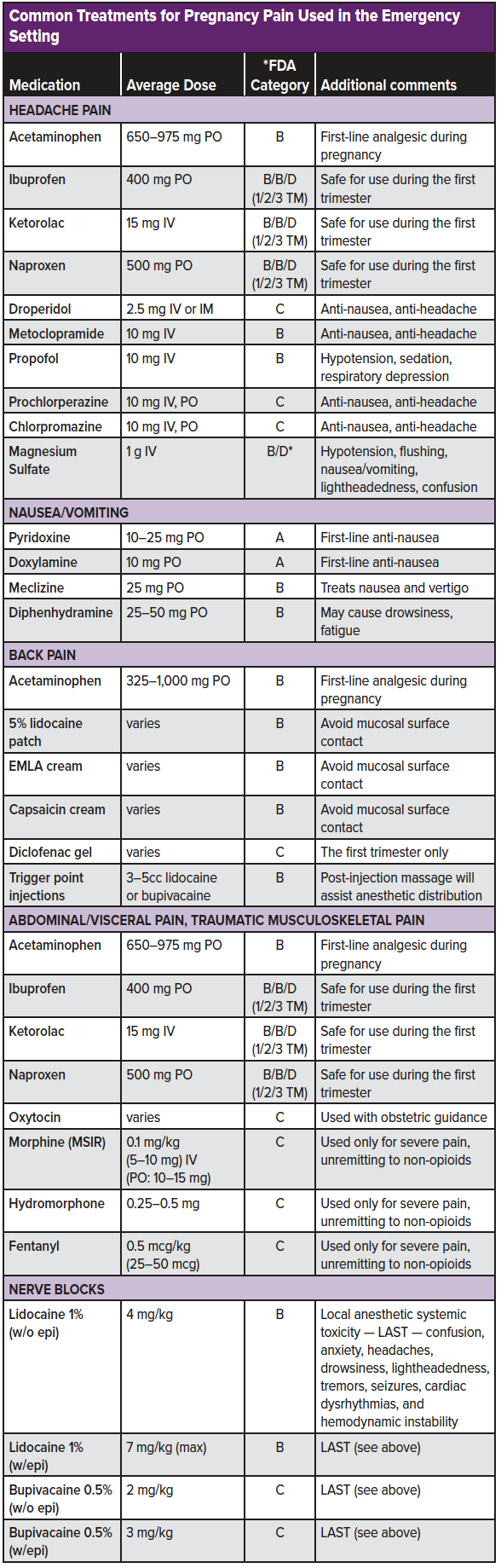

Headache pain: Among pregnant patients in whom preeclampsia and other life-threatening diagnoses have been considered, acetaminophen 650-975 mg PO is a first-line analgesic choice. For headaches resistant to oral acetaminophen, a general approach to migraine-type headache pain should be considered. Safe pregnancy options include metoclopramide (10 mg IV), prochlorperazine (10 mg IV, PO), chlorpromazine (12.5 mg IV, PO), or droperidol (2.5 mg IV, IM).43,45,47,52,55,58 A greater occipital nerve block may also be considered (see migraine chapter). As metoclopramide is the only category B antidopaminergic, it should be regarded as the first line antidopaminergic agent.

In patients presenting with headache and associated nausea, metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, chlorpromazine, and droperidol also function as antiemetics. The combination pyridoxine (up to 10-25 mg PO for concomitant hyperemesis gravidarum) + doxylamine (up to 10mg PO for concomitant hyperemesis gravidarum), meclizine (25mg PO), or diphenhydramine (25-50 mg PO) may further assist in symptom relief.49,48,57 Intravenous fluids should be considered in all pregnant females who appear dehydrated or cannot tolerate oral fluids.

Headache adjunctions include magnesium and sub-anesthetic dose propofol. Magnesium (1 g IV) appears to be most efficacious in treating migraines with aura.42,44 Although magnesium is listed as category D, this rating is based on large doses (4-6 g) given over days to serve as a tocolytic – significantly more than the 1g single-use administration used for migraine headache relief. Sub-anesthetic doses of propofol 10 mg IV every 5 minutes (max 100 mg) may be considered as a last resort for refractory migraines. However, cardiac monitoring and provider observation are required to avoid over-sedation.

Back pain: Although NSAIDs are considered first-line treatment for acute, non-traumatic back pain, they are contraindicated among pregnant patients (outside of the first trimester). Furthermore, benzodiazepines and skeletal muscle relaxants have teratogenic effects and should be avoided. Topical analgesic formulations such as 4% of 5% lidocaine patch, EMLA cream, and capsaicin cream may be considered. Trigger point injections with a local anesthetic may further relieve myofascial irritation (see back pain chapter). Despite a limited amount of evidence, non-pharmacologic treatment modalities should also be considered (see the section below). Bed rest should be avoided, and the patient should remain active as tolerated.

Abdominal/visceral pain: Similar to headaches, acetaminophen, and non-opioid analgesics are considered the first-line regimen. When moderate/severe pain presents unresponsive to non-opioid analgesic options, opioids may be considered. All opioids have a similar safety profile during pregnancy (Class C). However, the Collaborative Perinatal Project demonstrated that exposure to codeine increased the risk of respiratory malformation. Codeine carries the additional risk of cardiovascular and oral cleft risks and should be avoided during pregnancy.3,14 As with all opioid use, the lowest effective dose should be used when being administered in the emergency setting.

Traumatic pain: Trauma is the leading non-obstetric cause of death during pregnancy.51 Although a full trauma review is beyond the scope of this chapter, a review of analgesia optimization is warranted. As discussed in the musculoskeletal chapter, moderate to severe traumatic pain is often refractory to the traditional oral analgesic regimen and will require parenteral opioids for analgesic relief. When used, opioids should be administered in a "start low, go slow" approach, focusing on delivering the smallest amount needed for analgesic efficacy for the shortest duration possible.

An alternative to opioids for traumatic pain during pregnancy is ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia (aka, nerve blocks). Nerve blocks are a simple-to-learn, easy-to-use, a non-opioid analgesic technique that can result in significantly improved 'door-to-analgesia' time for traumatic patients.46 With the major consideration being to limit the amount of anesthetic that crosses the placental barrier, bupivacaine is known to have the lowest fetal-to-maternal ratio and may be considered the local anesthetic of choice among pregnant patients.41

Emerging Pain Management Options

Oxytocin (Pitocin): Linked intrinsically with pregnancy and the intrapartum period, oxytocin has been demonstrated to be a safe and effective hormone for decreasing pain sensitivity with minimal side effects or risk to fetal development.15 In a variety of human and animal models, administration of oxytocin has been shown to reduce pain sensitivity and increase pain inhibition.16 While oxytocin can be administered intravenously and intramuscularly, several studies have demonstrated efficacy with intranasal oxytocin administration.15,16 These studies found daily intranasal oxytocin reduces headache, abdominal pain, and chronic pelvic pain, while continuous intravenous administration of oxytocin generates a dose-dependent decrease in intra-abdominal pain.17–21 Further research is needed regarding the safety and efficacy of oxytocin use in the emergency setting, and any use should occur only after discussing the case with the obstetric consult service.

Non-pharmacologic Alternatives

A multimodality treatment strategy involving both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic alternatives should always be encouraged as the first-line treatment for common pain presentations in pregnancy. Patients who engage in physical therapy in conjunction with education on ergonomics have lower pain levels, higher quality of life, and reduced disability during pregnancy.22 Additionally, acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and water therapy have all demonstrated efficacy in treating low back pain, though care should be taken with acupuncture not to stimulate the uterus or cervix, which may induce labor.22–27,56 In addition to its utility in low back pain, aqua-therapy has also been shown to decrease pelvic pain in pregnancy and reduce missed workdays among women during pregnancy.28

Disposition

The vast majority of these patients will be treated in the ED and discharged home to follow up with their obstetric care manager. Among patients with severe, intractable pain or those unable to tolerate oral medications and fluids, admission for observation, pain control, and further resuscitation should be discussed with the inpatient obstetrics team.

List of analgesic options based on FDA Pregnancy Drug Classification (The category D recommendation for magnesium sulfate is based on large doses (4-6g) given over days to serve as a tocolytic – significantly more than the 1 g single-use administration used for migraine relief). Source: Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products; Requirements for Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling (Federal Register/Vol 73, No. 104/May 29, 2008)

Please note: Under the 2014 Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule, the FDA replaced A/B/C/D/X drug categories in pregnancy with new labels containing more risk details. Implementation is ongoing.

References

- Vladutiu CJ, Stringer EM, Kandasamy V, Ruppenkamp J, Menard MK. Emergency Care Utilization Among Pregnant Medicaid Recipients in North Carolina: An Analysis Using Linked Claims and Birth Records. Matern Child Health J. 2019;23(2):265-276. doi:10.1007/s10995-018-2651-6

- Thangarajah F, Baur C, Hamacher S, Mallmann P, Kirn V. Emergency department use during pregnancy: a prospective observational study in a single center institution. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;297(5):1131-1135. doi:10.1007/s00404-018-4684-x

- Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Rathmell JP, et al. Patterns of opioid utilization in pregnancy in a large cohort of commercial insurance beneficiaries in the United States. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(5):1216-1224. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000172

- Rathmell JP, Viscomi CM, Ashburn MA. Management of Non-obstetric Pain During Pregnancy and Lactation. Anesth Analg. 1997;85(5):1074-1087. doi:10.1097/00000539-199711000-00021

- Shah S, Banh ET, Koury K, Bhatia G, Nandi R, Gulur P. Pain Management in Pregnancy: Multimodal Approaches. 2015. doi:10.1155/2015/987483

- Hobson-Webb LD, Juel VC. Common Entrapment Neuropathies. Contin Lifelong Learn Neurol. 2017;23(2):487-511. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000452

- Peleg R, Gohar J, Koretz M, Peleg A. Abdominal wall pain in pregnant women caused by thoracic lateral cutaneous nerve entrapment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;74(2):169-171. doi:10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00114-0

- Eslamian L, Jalili Z, Jamal A, Marsoosi V, Movafegh A. Transversus abdominis plane block reduces postoperative pain intensity and analgesic consumption in elective cesarean delivery under general anesthesia. J Anesth. 2012;26(3):334-338. doi:10.1007/s00540-012-1336-3

- Jadon A, Jain P, Chakraborty S, et al. Role of ultrasound guided transversus abdominis plane block as a component of multimodal analgesic regimen for lower segment caesarean section: a randomized double blind clinical study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18(1):53. doi:10.1186/s12871-018-0512-x

- Mabie WC. Peripheral Neuropathies During Pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(1):57-66. doi:10.1097/01.grf.0000153207.85996.4e

- Black RA, Hill DA. Over-the-counter medications in pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(12):2517-2524. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12825840. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Daniel S, Koren G, Lunenfeld E, Bilenko N, Ratzon R, Levy A. Fetal exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and spontaneous abortions. Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186(5):E177-E182. doi:10.1503/cmaj.130605

- Padberg S, Tissen-Diabaté T, Dathe K, et al. Safety of diclofenac use during early pregnancy: A prospective observational cohort study. Reprod Toxicol. 2018;77:122-129. doi:10.1016/J.REPROTOX.2018.02.007

- Saxén I. Associations Between Oral Clefts and Drugs Taken During Pregnancy. Int J Epidemiol. 1975;4(1):37-44. doi:10.1093/ije/4.1.37

- Rash JA, Aguirre-Camacho A, Campbell TS. Oxytocin and Pain. Clin J Pain. 2013;30(5):1. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31829f57df

- Boll S, Almeida de Minas AC, Raftogianni A, Herpertz SC, Grinevich V. Oxytocin and Pain Perception: From Animal Models to Human Research. Neuroscience. 2018;387:149-161. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.09.041

- Yang J. Intrathecal Administration of Oxytocin Induces Analgesia in Low Back Pain Involving the Endogenous Opiate Peptide System. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(8):867-871. doi:10.1097/00007632-199404150-00001

- Rash JA, Toivonen K, Robert M, et al. Protocol for a placebo-controlled, within-participants crossover trial evaluating the efficacy of intranasal Oxytocin to improve pain and function among women with chronic pelvic musculoskeletal pain. BMJ Open. 2017;7:14909. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016

- González-Hernández A, Rojas-Piloni G, Condés-Lara M. Oxytocin and analgesia: future trends. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35(11):549-551. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2014.09.004

- Ohlsson B, Truedsson M, Bengtsson M, et al. Effects of long-term treatment with Oxytocin in chronic constipation; a double blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17(5):697-704. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00679.x

- Louvel D, Delvaux M, Felez A, et al. Oxytocin increases thresholds of colonic visceral perception in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1996;39(5):741-747. doi:10.1136/gut.39.5.741

- Borg-Stein J, Dugan SA. Musculoskeletal Disorders of Pregnancy, Delivery and Postpartum. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18(3):459-476. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2007.05.005

- Sabino J, Grauer JN. Pregnancy and low back pain. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(2):137-141. doi:10.1007/s12178-008-9021-8

- Pennick V, Liddle SD. Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. In: Pennick V, ed. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013:CD001139. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001139.pub3

- Fitzgerald CM. Pregnancy and Postpartum-Related Pain. In: Pain in Women. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013:201-217. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7113-5_9

- Granath AB, Hellgren MSE, Gunnarsson RK. Water Aerobics Reduces Sick Leave due to Low Back Pain During Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(4):465-471. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00066.x

- Keskin EA, Onur O, Keskin HL, Gumus II, Kafali H, Turhan N. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Improves Low Back Pain during Pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2012;74(1):76-83. doi:10.1159/000337720

- Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(6):794-819. doi:10.1007/s00586-008-0602-4

- Sutter MB, Leeman L, Hsi A. Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41(2):317-334. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2014.02.010

- Kocherlakota P, Harper RG, Stern G. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):e547-61. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3524

- Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and Associated Health Care Expenditures. JAMA. 2012;307(18):1934-1940. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.3951

- Grossman M, Seashore C, Holmes AV. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Management: A Review of Recent Evidence. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12(4):226-232. doi:10.2174/1574887112666170816144818

- Logan BA, Brown MS, Hayes MJ. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: treatment and pediatric outcomes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56(1):186-192. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e31827feea4

- Hudak ML, Tan RC, COMMITTEE ON DRUGS, COMMITTEE ON FETUS AND NEWBORN, American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal Drug Withdrawal. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e540-e560. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3212

- Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2320-2331. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1005359

- Backes CH, Backes CR, Gardner D, Nankervis CA, Giannone PJ, Cordero L. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: transitioning methadone-treated infants from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Perinatol. 2012;32(6):425-430. doi:10.1038/jp.2011.114

- Moses-Kolko EL, Bogen D, Perel J, et al. Neonatal Signs After Late In Utero Exposure to Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. JAMA. 2005;293(19):2372. doi:10.1001/jama.293.19.2372

- Finnegan LP, Connaughton JF, Kron RE, Emich JP. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: assessment and management. Addict Dis. 1975;2(1-2):141-158. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1163358. Accessed September 11, 2019.

- Osborn DA, Jeffery HE, Cole MJ. Opiate treatment for opiate withdrawal in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD002059. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002059.pub3

- Kraft WK, van den Anker JN. Pharmacologic management of the opioid neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012;59(5):1147-1165. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2012.07.006

- Becker DE, Reed KL. Essentials of local anesthetic pharmacology. Anesth Prog. 2006;53(3):98-108; quiz 9-10.

- Bigal, M.E., et al., Intravenous magnesium sulphate in the acute treatment of migraine without aura and migraine with aura. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia, 2002. 22(5): p. 345-53.

- Cameron, J.D., P.L. Lane, and M. Speechley, Intravenous chlorpromazine vs intravenous metoclopramide in acute migraine headache. Acad Emerg Med, 1995. 2(7): p. 597-602.

- Delavar Kasmaei, H., et al., Ketorolac versus Magnesium Sulfate in Migraine Headache Pain Management; a Preliminary Study. Emerg (Tehran), 2017. 5(1): p. e2.

- Einarson A, Koren G, Bergman U. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: a comparative European study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;76(1):1-3.

- Johnson B, Herring A, Shah S, Krosin M, Mantuani D, Nagdev A. Door-to-block time: prioritizing acute pain management for femoral fractures in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(7):801-3. Lacasse A, Lagoutte A, Ferreira E, Berard A. Metoclopramide and diphenhydramine in the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum: effectiveness and predictors of rehospitalisation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;143(1):43-9.

- Li Q, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, Yau WP, Hernandez-Diaz S. Assessment of antihistamine use in early pregnancy and birth defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(6):666-74 e1.

- Matthews A, Haas DM, O'Mathuna DP, Dowswell T. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(9):CD007575.

- Melhado EM, Maciel JA, Jr., Guerreiro CA. Headache during gestation: evaluation of 1101 women. Can J Neurol Sci. 2007;34(2):187-92.

- Mendez-Figueroa H, Dahlke JD, Vrees RA, Rouse DJ. Trauma in pregnancy: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(1):1–10

- Miner, J.R., et al., Droperidol vs. prochlorperazine for benign headaches in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med, 2001. 8(9): p. 873-9.

- Moshtaghion, H., et al., The Efficacy of Propofol vs. Subcutaneous Sumatriptan for Treatment of Acute Migraine Headaches in the Emergency Department: A Double-Blinded Clinical Trial. Pain Pract, 2015. 15(8): p. 701-5.

- Motov, S., et al., Comparison of Oral Ibuprofen at Three Single-Dose Regimens for Treating Acute Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med, 2019.

- Pasternak B, Svanstrom H, Molgaard-Nielsen D, Melbye M, Hviid A. Metoclopramide in pregnancy and risk of major congenital malformations and fetal death. JAMA. 2013;310(15):1601-11.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P. Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-30.

- Shapiro S, Kaufman DW, Rosenberg L, Slone D, Monson RR, Siskind V, et al. Meclizine in pregnancy in relation to congenital malformations. Br Med J. 1978;1(6111):483.

- Wang SJ, Silberstein SD, Young WB. Droperidol treatment of status migrainosus and refractory migraine. Headache. 1997;37(6):377-82.