Ch. 9 - Dermatologic Pain

Adam Kenney, MD | Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

Rochelle Kling, MD | Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

Dermatologic pain can be classified as nociceptive, inflammatory, or neuropathic. Acute or nociceptive pain is part of a rapid warning relay system, which instructs the motor neurons of the central nervous system to minimize detected physical harm. Inflammatory pain is associated with tissue damage and resulting inflammation. Damage to the neurons in the peripheral and central nervous system produces neuropathic pain and involves the sensitization of these systems.1

Pain management is often required for acute dermatologic conditions such as cellulitis, abscesses, acute contact dermatitis (ACD), and critical burns. Dermatologic pain pathology may also necessitate long-term adjunctive pain management in addition to the treatment of primary skin disease. Finally, chronic systemic conditions treated by dermatologists, such as psoriasis, morphea, and systemic lupus erythematosus, can feature prominent, disabling, chronic pain sequelae.2

Skin conditions are common in the general population. The prevalence of dermatologic conditions requiring medical treatment is estimated at 19% to 27% of the population.3,4 Historical analysis has shown dermatologic complaints account for approximately 7% of all outpatient clinic visits and approximately 3.3% of all emergency department (ED) visits. 5 Most ED cases were triaged as either non-urgent or semi-urgent, with only 2% fulfilling emergency status. Ninety-four percent of patients who present to the ED are discharged home, while only 4% required inpatient admission. Skin infection (abscess, cellulitis) were responsible for more than half of ED visits followed by dermatitis, and urticaria.6

This chapter will focus on the recognition and assessment of common dermatologic pain presentations in the ED as well as the pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment options that can be used to relieve dermatologic pain. Common pearls and pitfalls, as well as patient disposition, will also be reviewed.

CELLULITIS

Cellulitis presentations account for 2.3 million ED visits annually.7 Cellulitis is defined as an infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissues of the skin, characterized by erythema, warmth, edema, and pain. Despite the common presentation and rapid recognition, a thorough assessment should focus on distinguishing cellulitis from life and limb-threatening cellulitis mimics such as a necrotizing infection and underlying systemic inflammatory diseases (SLE, HIV, rheumatoid arthritis). The time course of symptoms helps distinguish cellulitis from a mimic. Cellulitis begins over 2-3 days and will typically resolve within 24-48 hours after initiating antibiotics.

Patients with cellulitis will typically present with mild to moderate pain. The primary mode to relieve pain is to treat the underlying pathology with a course of antibiotics. Research has demonstrated no difference in patient-reported pain relief when adding ibuprofen (versus placebo) to antibiotics for uncomplicated cellulitis.8

However, a complaint of severe pain in the setting of cellulitis should alert the emergency physician to consider an escalated analgesic modality. The first-choice analgesia in a patient with mild cellulitis is an oral (PO) dose of ibuprofen 400–800 mg PO. In cases where oral ibuprofen provides inadequate pain relief, acetaminophen 650–1,000 mg PO may act synergistically with ibuprofen to increase the analgesic efficacy.9,10 Ketorolac 15–30 mg IV may also be used as an effective parenteral NSAID option.

If the pain persists despite the use of oral non-opioids (ibuprofen 400 mg PO + acetaminophen 1000 mg PO), the next choice of analgesic for acute pain in a patient with uncomplicated cellulitis would be either a non-opioid adjunct such as sub-dissociative dose ketamine or a nerve block.

Subdissociative-dose ketamine 0.1–0.3 mg/kg IV (given slowly over 10 minutes) can be as an adjunct to opioids or as an opioid alternative, particularly when any form of manipulation or drainage is required. Commonly experienced adverse side effects of ketamine, including dizziness, dysphoria, hallucinations, disorientation, lightheadedness, and confusion. These effects can be limited when given as a slow intravenous infusion. It is important to note that the use of ketamine has not specifically been studied in the setting of dermatologic pain, and further research is needed to understand the efficacy under these conditions.

Field Blocks (and nerve blocks) are an effective method of providing anesthesia for the treatment of severe cellulitis. In a field block, a local anesthetic is infiltrated into the subcutaneous tissue around the border of the cellulitis. The needle is inserted at two different points, and the anesthetic solution is injected into four different lines that surround the entire affected region.11 Epinephrine may be added to the anesthetic to enhance vasoconstriction and prolong the duration of anesthesia. If the cellulitis extends over a larger region, a nerve block involving the injection of a local anesthetic directly adjacent to the nerve supplying the affected tissue is an effective means of analgesic relief (see the chapter on nerve blocks for further discussion).

In general, opioids should play a minimal role in the management of pain due to uncomplicated cellulitis of mild to moderate in severity. In the setting of severe pain, unresponsive to first-line analgesic efforts, intravenous opioids (fentanyl or morphine) may be considered for severe pain with a “start low, go slow” approach to prevent overdosing. Either morphine 5–10 mg PO or 0.05–0.1 mg/kg IV may be used as a first-line opioid analgesic in a hemodynamically stable patient without contraindications. Nebulized morphine (10 mg) has also been shown to offer similar analgesic relief compared to intravenous formulations for acute traumatic pain.47 Fentanyl has the advantage of acting rapidly with an initial dose of 1–1.5 mcg/kg IV and repeated doses of 0.25–0.5 mcg/kg every 15 minutes, titrated to analgesic relief. Subcutaneous morphine administration may also be considered if IV access is not available.

The disposition of a patient with cellulitis is based on the severity of infection, presence of comorbidities, availability of home health needs, and pain control. The vast majority of cellulitis cases do not require inpatient admission. Advising the patient to rest and elevate the affected area and apply intermittent cold compresses will improve swelling, thereby working in conjunction with pharmacologic treatments to enhance patient discomfort.13

ABSCESS

Cutaneous abscesses are focal collections of pus located within the dermis and hypodermis, which typically present as “painful, tender, and fluctuant red nodules, surrounded by a rim of erythematous swelling.” 14 Fluctuance is a classic hallmark of abscesses, although it may be absent in the early stages of formation or a deep subcutaneous abscess. As with cellulitis, it is essential to rule out other infectious skin conditions that may mimic an abscess.15 Careful palpation for fluctuance is considered the first-line “diagnostic test” for a cutaneous abscess and, in many cases, is all that is required to feel confident about the diagnosis based on strong suspicion. Ultrasound examination is a useful adjunct to the physical examination when fluctuance is absent or difficult to localize. If uncertain about the diagnosis and concern for the spread of underlying infection, a computer tomography (CT) scan may be used for deep subcutaneous, intramuscular abscess, and the evaluation of perineum and neck abscesses.

The primary treatment modality of a cutaneous abscess is incision and drainage (I&D). Patients who present with superficial cutaneous abscess experience two distinct categories of pain, moderate to severe baseline pain due to the stretching of the abscess itself, as well as the high-intensity procedural pain brought on during the I&D. Successful incision and drainage rely heavily on patient comfort. Achieving adequate anesthesia of abscesses can be challenging, as even the best technique may prevent the sensation of sharp pain but not the tension and pressure of breaking up adhesions.16

Pain is often what prompts a visit to the ED and should be addressed as soon as possible. The definitive treatment for abscess-related pain is drainage. At this time, there are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing optimal pain control for I&D of superficial cutaneous abscesses. The traditional approach of ibuprofen 400 mg PO and acetaminophen (paracetamol) 1,000 mg PO is often insufficient analgesic relief for procedural drainage. Ketorolac 15–30 mg IV is considered a safe and effective first-line non-opioid analgesic for mild to moderate abscess-related pain in patients without contraindications to NSAIDs. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks are a simple-to-learn, easy-to-use, non-opioid analgesic technique that should also be considered a first-line analgesic in treating abscess pain (see ultrasound-guided nerve block chapter for further discussion). As with cellulitis, if severe pain persists despite the mentioned first-line options, opioids (morphine, fentanyl) may be considered.

Infiltration of the abscess with local anesthesia (lidocaine, bupivacaine) before I&D using may further assist in the procedure-associated pain. In order to minimize the pain of the injection, consider buffering lidocaine to a neutral pH (using a 1:10 mixture of 8.4% bicarbonate: 1% lidocaine with epinephrine), injecting slowly through a small needle, using the lowest volume necessary, and warming the anesthetic to body temperature before injection.17-19 The needle should be inserted through areas of the skin that have already been anesthetized, or begin injection at the wound edges rather than through intact skin.20,21 While not supported by evidence, one pearl used by the authors with success is to make a small stab incision into an extremely tense abscess prior to anesthetic use to avoid the tension-associated pain. This serves to significantly reduce the pain caused by the pressure of the abscess and creates more room for the anesthetic infiltration.

Vapocoolants (cold sprays) are rapid-acting evaporation-induced skin cooling, which has been shown to reduce pain for children undergoing IV cannulation compared with placebo. They are approved for topical application to control pain associated with minor surgical procedures (such as lancing boils and incision and drainage of small abscesses).22 Gebauer’s Ethyl Chloride is one of the more readily available vapocoolants for pre-procedural analgesia. The anesthetic duration of Gebauer’s Ethyl Chloride lasts a few seconds to a minute but may be applied prior to the initial incision as an analgesic adjunct.23 Given the short duration of action, vapocoolant sprays should not be used as the sole method of anesthesia prior to incision and drainage.

Topical anesthetics have the advantage of sparing the patient from a painful injection of local anesthetic into the abscess, an environment that is difficult to anesthetize in the first place. Though not commonly used in the setting of abscess I&D, one retrospective chart review found an association between the use of topical LMX-4 (Liposomal Lidocaine 4%) and a reduced need for procedural sedation following application prior to I&D.24

In addition to pharmacologic methods, non-pharmacologic methods for abscess drainage -related pain are a useful and effective adjunct for pain control during I&D. Non-pharmacologic methods include conversation distraction, or tactile distractions, including pinching, stretching, pressing, or tapping near needle insertion sites.25,26 Ice may further slow conduction of peripheral nerve fibers, promoting sensory competition, and decreasing the release of inflammatory and nociceptive mediators.27 Ice is cheap, readily available, has a rapid onset, and has been utilized as an analgesic for subcutaneous and intramuscular injections with favorable results.28,29 Considering the safety of this non-pharmacologic option, ice should be used as an adjunct to the multimodal pain control approach used both before and after abscess I&D.

Similar to cellulitis, the disposition of a patient with an abscess is based on the severity of infection, presence of comorbidities, availability of home health needs, and pain control. The vast majority of cases do not require inpatient admission and can be discharged home with proper wound care instructions and close outpatient follow up.

BURNS

An estimated 1.25 million burn injuries occur annually in the United States, resulting in more than 51,000 acute hospitalizations. Acute burn injury pain results from the combination of thermal tissue injury and an acute inflammatory response proportional to the depth of tissue injury.30,31 Depending on the extent of the injury, burn pain can range from mild to severe. Burn severity should be determined by a combination of total body surface area, depth, anatomic location, and mechanism of injury. Accurate estimation of burn depth may be challenging based on visual estimation where experienced burn surgeons were only 60-70% accurate at estimating based on visual exam alone.32,33 When in doubt, erring on the side of increased severity will avoid undertreatment of the patient’s pain.

First-degree burns (eg, sunburn) are characterized by tissue injury and inflammatory response in the superficial dermal layers. First degree burns range from mild to moderate pain. Initial treatment of isolated, minor thermal injuries consists mainly of removing clothing and debris, cooling, simple cleansing, appropriate skin dressing, pain management, and tetanus prophylaxis. To be considered a minor burn, it must be: an isolated injury (no associated inhalation injury or high voltage injury), does not involve face, hands, perineum or feet, does not cross major joints, and is not circumferential.34 For superficial minor burns, oral acetaminophen or NSAIDs may provide adequate analgesic relief. Non-open wounds may further benefit from the administration of topical analgesics such as diclofenac, ketoprofen, ibuprofen, or EMLA cream. Additionally, non-pharmacologic analgesia, including oatmeal baths, cold compresses, aloe vera, cacao butter, and calamine lotion, should be considered.

Partial-thickness to full-thickness burns can be exquisitely painful. Research has shown that pain experienced during the early hospitalization period may predict long-term outcomes35 and positively correlated with symptoms of PTSD.36 Early recognition and management of burn injury is critical for the long-term physical and psychological well-being of patients with burn injuries.37 Traditionally, IV opioids were the mainstay of pain management for patients with severe burn pain. However, long-term opioid use is associated with adverse side effects, pain hypersensitivity, and the risk for dependency and abuse that has led clinicians to explore alternative (non-opioid) approaches to pain management that includes neuropathic medications, as well as interventional and adjuvant therapies.38

In the immediate setting, burn patients can benefit from interventional ultrasound-guided nerve blocks (see the chapter on ultrasound-guided nerve blocks).55 Analgesic adjuncts such low-dose ketamine 0.1–0.3 mg/kg IV, may also be used to treat burn pain.51 Dexmedetomidine has been shown to reduce opioid consumption, decrease opioid side effect profile, and improve patient satisfaction in the postoperative setting56 and may also be considered for acute burn pain relief. Dexmedetomidine can be delivered IV or IN with recommended dosing of 0.5–1.0 μg/kg IV (1 to 2 μg/kg intranasal) used for acute pain relief.49 IV lidocaine may also be considered a useful analgesic adjunct to opioids or an analgesic alternative when NSAIDs are contraindicated. Intravenous lidocaine (1.5 mg/kg IV) has been shown to offer a quick onset and an extended duration of analgesic relief for mild to moderate pain pathologies.

Topical NSAIDs may also be considered for superficial burns with intact skin. As opposed to PO and IV analgesics, which require systemic distribution, topical/transdermal analgesics use localized analgesic distribution to limit total-body quantities delivered. Topical analgesics are optimal in patients with renal disease or elderly patients susceptible to elevated analgesic plasma concentrations and in patients with multiple comorbidities such as peptic ulcer disease and cardiovascular disease in which PO NSAIDs are relatively contraindicated. Examples of topical analgesics include diclofenac, ketoprofen, ibuprofen, 5% lidocaine patch, and EMLA cream. In addition to burns, other dermatologic pain pathologies that benefit from topical analgesics include neuropathies, skin or leg ulcers, and acute herpetic zoster.43, 45,48,50,53,54

To improve long-term burn injury outcomes, non-pharmacologic analgesic modalities such as psychological counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness, music therapy, hypnosis, and the use of virtual reality technology may be used as adjuncts.

LACERATION REPAIR

Lacerations are another frequently encountered soft tissue pathology that requires adequate analgesia for optimal management. The two main options for managing pain associated with laceration repair include the infiltration of local anesthetic and topical anesthetics. Similar to almost all cutaneous pain pathologies, nerve blocks are another method of providing analgesia prior to laceration repair and are especially useful for large lacerations or lacerations located in sensitive regions.

In addition to nerve blocks, topical anesthetics should be considered as an adjunct for pain management prior to laceration repair and prior to anesthetic injection. LET sterile gel is composed of 4% lidocaine, 0.1% adrenaline, and 0.5% tetracaine hydrochloride and is a commonly available topical anesthetic in an emergency setting.39 LET can be applied to laceration wounds, secured with an adhesive dressing, and left in place for a maximum of 30 minutes.

VENIPUNCTURE

Peripheral intravenous (PIV) catheter insertion is a frequent, painful procedure that is often performed with little or no anesthesia.40 Current approaches that minimize pain for PIV catheter insertion include topical anesthetics such as LET or EMLA®, an anesthetic formulation defined as a eutectic mixture of local anesthetic drugs composed of a combination of 2.5% prilocaine and 2.5% lidocaine. EMLA is indicated as a topical anesthetic for use on healthy intact skin for local analgesia and is most frequently used as a pre-treatment for venipuncture in children. According to the company instructions, EMLA should be applied under an occlusive dressing for at least 1 hour, making it somewhat impractical in the ED.

Vapocoolant spray may also be used prior to venipuncture. In one meta-analysis, vapocoolant spray significantly decreased pain during intravenous cannulation when compared with placebo spray or no treatment in both adults and children.41

An alternative to topical anesthetic creams is the needle-free jet injection system with buffered lidocaine (J-Tip). The J-Tip uses carbon dioxide instead of a needle to deliver 0.2 mL of 1% buffered lidocaine into the skin. Local analgesia is experienced at the site of administration in less than 1 minute. Four randomized clinical trials conducted in the ED or preoperative setting in children aged 1 to 19 years found that the J-Tip was superior for the treatment of pain during venipuncture or IV-line placement when compared with topical anesthetic or placebo.42

ALLERGIC CONTACT DERMATITIS

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is one of the most common dermatologic presentations in the ED with ACD secondary to urushiol toxicity (eg, poison oak, sumac, and ivy) representing the single most common ACD in North America. Urushiol-dermatitis is estimated to affect 10-50 million individuals per year. The common presentation includes a weeping, pruritic rash that can result in extreme pain (secondary to excoriations) and discomfort if left untreated.52

The mainstay for urushiol-dermatitis treatment involves early recognition (before symptom manifestation) by removing all contaminated clothing and jewelry, gently rinsing away the oils with cold water, and following with a mild soap cleansing. However, most exposures are unrecognized until progressive symptoms develop.

Topical corticosteroids are considered first-line treatment for ACD.44 Systemic corticosteroids are often needed for ACD covering >20% of the skin surface.46 Systemic steroids may be initiated in the emergency department, though a single dose is often insufficient. Prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day (max 60 mg PO) for 7 days (or a 5-7-day methylprednisolone pack) is often the recommended first-line systemic steroid regimen.46 Tapering is typically not needed for a 7-day course. Non-pharmacologic treatments such as oatmeal baths, cold compresses, and calamine lotion may also be used as an adjunct to pharmacologic analgesics.

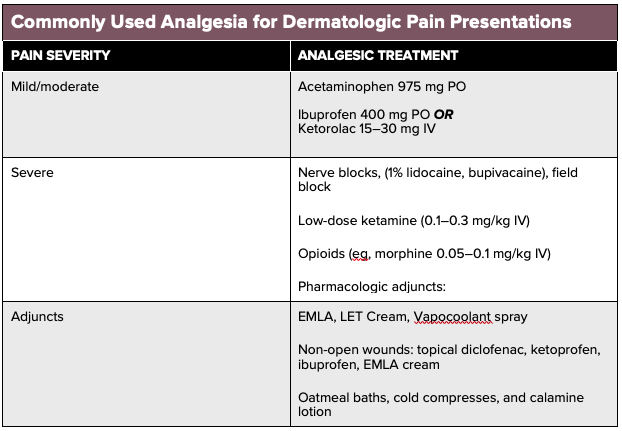

See table for a listing of commonly used analgesics for each dermatologic pain presentation.

SUMMARY

Dermatologic presentations to the emergency department are not infrequent, with the majority associated with painful conditions due to an underlying process of tissue destruction such as cellulitis, abscess, burns, and lacerations. Once life-threatening infections have been ruled out, management of dermatologic pain focuses on treating the underlying condition with pain control serving as an adjunct to improving the patient’s symptoms. Except for severe presentations, which may require parenteral opioids, non-opioid analgesics are the mainstay of pain therapy for these dermatologic entities. With the use of a combination of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic analgesic modalities, high-dose opioids may be avoided while still achieving successful analgesic relief.

References

- Twaddle ML, Cooke KJ. Assessment of pain and common pain syndromes. In: von Roenn JH, Paice JA, Preodor ME, editors. Current diagnosis and treatment: pain. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw Hill, 2006. pp. 10–20.

- Enamandram M, Rathmell JP, Kimball AB. Chronic pain management in dermatology: A guide to assessment and non-opioid pharmacotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;73:563-73.

- Schaefer I, Rustenbach SJ, Zimmer L, Augustin M. Prevalence of skin diseases in a cohort of 48,665 employees in Germany. Dermatology. 2008;217 (2):169-172.

- Kilkenny M, Stathakis V, Jolley D, Marks R. Maryborough skin health survey: prevalence and sources of advice for skin conditions. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39(4):233-237.

- Stern RS, Johnson ML, DeLozier J. Utilization of physician services for dermatologic complaints. The United States, 1974. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113 (8):1062-1066.

- Baibergenova A, Shear NH. Skin Conditions That Bring Patients to Emergency Departments. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(1):118–120.

- Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and consequences associated with misdiagnosed lower extremity cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol 2017;153:141–6.

- Davis JS, Mackrow C, Binks P, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of ibuprofen compared to placebo for uncomplicated cellulitis of the upper or lower limb. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2017;23(4):242-246.

- Hay D, Nesbitt V. Management of acute pain. Surgery (Oxford). 2019;37(8):460-466.

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a Single Dose of Oral Opioid and Nonopioid Analgesics on Acute Extremity Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017 Nov 7;318(17):1661-1667.

- McCreight A, Stephan M. Local and regional anesthesia. In: Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Procedures, 2nd edition, King, C, Henretig, FM (Eds), Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins, Philadelphia 2008. p.439.

- Brewer AR, McCarberg B, Argoff CE. Update on the use of topical NSAIDs for the treatment of soft tissue and musculoskeletal pain: a review of recent data and current treatment options. Phys Sports Med. 2010;38:62–70.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:e10–52.

- Kobayashi SD, Malachowa N, DeLeo FR. Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus abscesses. Am J Pathol 2015;185(6):1518–27.

- Breyre A, Frazee BW. Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in the Emergency Department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2018 Nov;36(4):723-750. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2018.06.005. Review. PubMed PMID: 30297001.

- Holtzman LC, Hitti E, Harrow J. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine. Chapter 37 Incision and Drainage. 719-757. E3

- Mader TJ, Playe SJ, Garb JL. Reducing the pain of local anesthetic infiltration: warming and buffering have a synergistic effect. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:550-554.

- Strazar R, Leynes PG, Lalonde DH. Minimizing the pain of local anesthesia injection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:675-684.

- Colaric KB, Overton DT, Moore K. Pain reduction in lidocaine administration through buffering and warming. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:353-356.

- Mustoe TA, Buck DW, Lalonde DH. The safe management of anesthesia, sedation, and pain in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;126(4):165e-76e.

- Kelly AM, Cohen M, Richards D. Minimizing the pain of local infiltration anesthesia for wounds by injection into the wound edges. J Emerg Med 1994;12(5):593-5.

- Griffith R, Jordan V, Herd D, Reed P, Dalziel SR. Vapocoolants (cold spray) for pain treatment during intravenous cannulation. 2016;2016.

- Gebauer Company. Painease. Technical Data Sheet. Available at: http://gebauer.com/getmedia/ 6ddc613b-142f-44cb-ac1f-b399cfb48854/PETS_ENG.aspx.

- Cassidy-Smith T, Mistry R, Russo C, et al. Topical anesthetic cream is associated with spontaneous cutaneous abscess drainage in children. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2010;30:104-109.

- Ong EL, Lim NL, Koay CK. Towards a pain free Venepuncture. Anesthesia. 2000 :260–262.

- Nanitsos E, Vartuli R, Forte A, Dennison PJ, Peck CC. The effect of vibration on pain during local anaesthesia injections. Aust Dent J. 2009;54:94–100.

- Ernst E, Fialka V. Ice Freezes Pain? A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness of Analgesic Cold Therapy. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1994; 9:56–59.

- Kuwuhara R, Skinner R. EMLA Versus Ice as Topical Anesthetic. Dermatologic Surgery. 2001; 27:495–496.

- Yoon WY, et al. Analgesic pretreatment for antibiotic skin test: vapocoolant spray vs. ice cube. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2008; 26:59–61.

- Patterson DR, Hoflund H, Espey K, Sharar S. Pain management. Burns. 2004;30(8):A10-A15.

- Faucher L.D., and Furukawa K.: Practice guidelines for the management of pain. J Burn Care Rehabil 2006; 27: pp. 659-668

- Monstrey S, Hoeksema H, Verbelen J, et al. Assessment of burn depth and burn wound healing potential. Burns 2008; 34:761.

- Serrano C, Boloix-Tortosa R, Gómez-Cía T, Acha B. Features identification for automatic burn classification. Burns 2015; 41:1883.

- Ulmer JF. Burn pain management: a guideline-based approach. J Burn Care Rehabil 1998; 19:151.

- Patterson DR, Tininenko J, Ptacek JT. Pain during burn hospitalization predicts long-term outcome. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:718-726

- McIntyre MK, Clifford JL, Maani CV, Burmeister DM. Progress of clinical practice on the management of burn-associated pain: Lessons from animal models. Burns. 2016;42(6):1161-1172.

- James DL, Jowza M. Principles of Burn Pain Management. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 2017;44(4):737-747.

- Mader TJ, Playe SJ, Garb JL. Reducing the pain of local anesthetic infiltration: warming and buffering have a synergistic effect. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:550-554.

- Johnson B, Herring A, Shah S, Krosin M, Mantuani D, Nagdev A. Door-to-block time: prioritizing acute pain management for femoral fractures in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:801-3.

- Marco CA, Cook A, Whitis J, et al. Pain scores for venipuncture among ED patients. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;35(1):183-184.

- Griffith R, Jordan V, Herd D, Reed P, Dalziel SR. Vapocoolants (cold spray) for pain treatment during intravenous cannulation. 2016;2016.

- Stoltz P, Manworren RCB. Comparison of Children’s Venipuncture Fear and Pain: Randomized Controlled Trial of EMLA® and J-Tip Needleless Injection System®. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2017;37:91-96.

- Argoff CE. Topical analgesics in the management of acute and chronic pain. Introduction. Postgrad Med. 2013;125(4 Suppl 1):3-6.

- Bourke J, Coulson I, English J, British Association of Dermatologists Therapy G, Audit S. Guidelines for the management of contact dermatitis: an update. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(5):946-54.

- Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Kalso EA, Bell RF, Aldington D, Phillips T, et al. Topical analgesics for acute and chronic pain in adults - an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD008609.

- Fonacier L, Bernstein DI, Pacheco K, Holness DL, Blessing-Moore J, Khan D, et al. Contact dermatitis: a practice parameter-update 2015. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3 Suppl):S1-39.

- Grissa MH, Boubaker H, Zorgati A, et al. Efficacy and safety of nebulized morphine given at 2 different doses compared to IV titrated morphine in trauma pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(11):1557-61.

- Leppert W, Malec-Milewska M, Zajaczkowska R, Wordliczek J. Transdermal and Topical Drug Administration in the Treatment of Pain. Molecules. 2018;23(3).

- Mahmoud M, Mason KP. Dexmedetomidine: review, update, and future considerations of paediatric perioperative and periprocedural applications and limitations. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(2):171-82.

- McCarberg B, D’Arcy Y. Options in topical therapies in the management of patients with acute pain. Postgrad Med. 2013;125(4 Suppl 1):19-24.

- McGuinness SK, Wasiak J, Cleland H, Symons J, Hogan L, Hucker T, et al. A systematic review of ketamine as an analgesic agent in adult burn injuries. Pain Med. 2011;12(10):1551-8.

- Pariser, D.M., Ceilley, R.I., Lefkovits, A.M., Katz, B.E., and Paller, A.S. Poison ivy, oak and sumac. Derm. Insights. 2003; 4: 26–28

- Sawynok J. Topical analgesics for neuropathic pain: preclinical exploration, clinical validation, future development. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(4):465-81.

- Serinken M, Eken C, Tunay K, Golcuk Y. Ketoprofen gel improves low back pain in addition to IV dexketoprofen: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1458-61.

- Shank ES, Martyn JA, Donelan MB, Perrone A, Firth PG, Driscoll DN. Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia for Pediatric Burn Reconstructive Surgery: A Prospective Study. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37(3):e213-7.

- Tang C, Xia Z. Dexmedetomidine in perioperative acute pain management: a non-opioid adjuvant analgesic. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1899-904.