Ch. 13 - Pain in Older Adults

Andrew K. Chang, MD, MS | Albany Medical Center

Due to medical and surgical progress, more people in the United States are reaching advanced age than ever before. However, medical conditions and pain ailments are common among older adults presenting to the emergency department (ED) with a wide variety of pain-related complaints.

Acute pain management, upon which this chapter will focus, is particularly challenging among older adults due to age-related physiological changes, increased frequency of comorbidities, variations in the degree of cognitive impairment, and an increased rate of drug-drug interactions.1 Effective treatment of acute pain should not only relieve suffering but revolve around a consideration of the age-related changes that are essential to providing safe outcomes during ED stay and hospitalization among older patients.2

PHYSIOLOGY OF AGING

The physiologic changes associated with aging impact the pharmacological treatment of older adults in pain. Older adults are typically defined as age 65 years and older. Some further subdivide this category into "young old" (age 65-74 years), "older old" (age 75-84 years), and "oldest old" (age 85 years and above). With age, gastrointestinal absorption slows and total body water and lean mass decrease while body fat increases.3 Because the volume of distribution increases, changes also occur with plasma concentration and elimination of drugs as renal and hepatic clearance decrease with age. Each of these physiologic variations affects pharmacologic absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion.

A review of medical comorbidities and prescriptions – particularly anticoagulants, sedative-hypnotics, and muscle relaxants – is advised before prescribing an analgesic agent. Between 30-40% of participants between the ages of 62 to 85 years have been using five or more prescription medications.4 An emergency provider should also consider the Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults, a list of medications that, in general, should be avoided in older adults, at least on a chronic use basis. Commonly used medications on this list include benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, tricyclic antidepressants, muscle relaxants, and NSAIDs (varying recommendations for avoidance).5

In assessing pain in older adults, one should be aware that cognitive impairment (eg, dementia) may limit the ability to self-report pain, which can cause the clinician to perceive (incorrectly) an absence of pain and result in undertreatment of pain pathology.6 However, research using fMRI evaluation has shown increased attention in cognitively impaired patients to noxious stimuli, emphasizing the importance of treating the pain pathology (eg, acute fracture), and not just the reported level of pain.7

ACUTE PAIN

A large proportion of ED visits among older adults stem from musculoskeletal injuries related to falls.8,9 Despite the low-impact of these falls, osteoporosis/osteopenia significantly increases the risk of fractures, and so the clinician should have a low threshold to order imaging. Older patients can also present with pain from various cardiac, vascular, abdominal, and genitourinary pathology, such as pyelonephritis or nephrolithiasis.

ACUTE EXACERBATION OF CHRONIC PAIN

Many older patients suffer from pain associated with advanced or terminal cancer, including pain secondary to bony metastases.10 Other examples include chronic inflammatory conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic low back pain, and neuropathic pain secondary to long-standing diseases such as stroke, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and coronary artery disease.

In general, non-opioid analgesia should be considered first-line therapy among patients presenting with chronic pain. For pain presentations unresponsive to non-opioid analgesia, short-acting opioids either via oral or parenteral routes may be used as a rescue analgesic. However, for older adults presenting to the ED with an acute worsening of chronic pain (eg, cancer-related pain) and who are already taking oral opioids, an intravenous opioid may be required for breakthrough pain presentations.

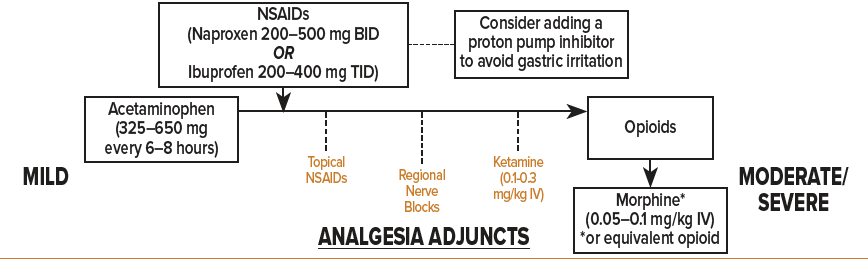

NON-OPIOIDS

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen (aka, paracetamol) is the recommended first-line therapy among older adults for mild to moderate pain by the American Geriatric Society (AGS).11 Acetaminophen 325-650 mg orally (recommended maximum 3 g per day) is considered a safe initial treatment for common mild to moderate pain ailments such as osteoarthritis and low back pain.12 A 2017 study found the combination of acetaminophen/ibuprofen was as effective as opioid-containing combinations when used for extremity pain in an emergency setting,13 though older adults were not included in this study and therefore further research is needed to evaluate for similar safety and efficacy of this combination of analgesics in older adults.

Intravenous formulations of acetaminophen are available. Acetaminophen 1 g IV administered over 15 min may be considered in situations where patients are unable to tolerate opioids or NSAIDs, or among older patients restricted from oral medication administration. Many institutions, however, currently restrict use of IV acetaminophen due to its expense. Further data is needed to assess the safety and efficacy of parenteral acetaminophen among older patients in the emergency setting.

Acetaminophen should be used with caution among patients with hepatic failure or a history of chronic alcohol abuse/dependence. Acetaminophen may cause a statistically (and possibly clinically) significant increase in INR among patients using warfarin.14 Although not directly contraindicated, if continued acetaminophen administration among older adults is recommended upon ED discharge, close follow-up of the INR is likely warranted.

As many patients who present to the ED may have already taken acetaminophen before they arrived to the ED, it is prudent to inquire about acetaminophen-containing analgesic ingestion before arrival. Acetaminophen overdose is also a risk when attempts to reach a suitable analgesic effect using opioid-acetaminophen combinations result in increased dosing of acetaminophen to achieve an analgesic effect.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

If the pain is not adequately controlled by acetaminophen, NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, naproxen, ketoprofen, and diclofenac may be used sparingly among older adults (ketorolac may also be used though less desired based Beers Criteria ‘avoidance’ listing). Some research has suggested that the analgesic ceiling is 400mg for oral ibuprofen and 10 mg for IV ketorolac.15,16 For mild acute pain, ibuprofen is dosed at 400 mg every 4-6 hours as needed with a maximum dose of 3,200 mg per day. A systematic review found 400 mg ibuprofen was superior to 1,000 mg acetaminophen for acute pain relief but noted that the combination of both ibuprofen and acetaminophen was superior to either analgesic agent alone.17

NSAIDs are included in the Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults.5 Medications listed on the list, however, typically refer to chronic medication use. Therefore, single dose and/or short-term ED use for acute pain may be considered and is generally thought to be safe. NSAIDs should be used cautiously in older adults with cardiovascular comorbidities, volume depletion, pre-existing renal or liver disease, peptic ulcer disease, or loop diuretic use as these place patients at higher risk of drug-induced acute renal failure.18 For gastric prophylaxis, consider administering a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) when treating with an NSAID in an older adult.19

NSAIDs also carry an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and disrupt the protective cardiovascular effects of aspirin.20,21 This increased risk has been demonstrated in patients with and without a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) when NSAIDs were taken for at least a 7-day duration.21,22 Even short-term use of NSAIDs has been associated with recurrent myocardial infarctions and death.23 Selective COX-2 inhibitors (celecoxib) and diclofenac were shown to confer an increased risk after as little as 7-14 days. Indomethacin and ketorolac have received a recommendation of "avoidance" from the 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults based on an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding/peptic ulcer disease, acute kidney injury in older adults, and CNS effects (indomethacin).5

Although there is no absolute safe therapeutic window,24 it is recommended to avoid NSAIDs in patients with significant cardiovascular disease and to limit the duration of NSAIDs for outpatient pain management to no more than a 3-5 days in older adults. Among patients receiving aspirin for cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention, it is recommended that NSAIDs be taken only as needed and at least 30 minutes after and 8 hours prior to immediate-release aspirin.21 When administering NSAIDs among older adults, it is important to regularly assess for cardiac, renal, and gastrointestinal side effects.25,26 Naproxen 200-500 mg BID, prn has demonstrated fewer adverse cardiovascular outcomes compared to the other NSAIDs.27 Ibuprofen 200-400 mg, prn TID may also be used if benefits outweigh the risks. The concomitant use of NSAIDs and ACE-Inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, corticosteroids, diuretics, SSRIs, warfarin and other anticoagulants should be limited.26

TOPICAL ANALGESICS

As opposed to oral and parenteral analgesics that require systemic distribution, topical/transdermal analgesics have the advantage of localized analgesic distribution which limits the total quantity of medication delivered.28 Topical NSAIDs preferably accumulate in targeted areas with concentrations up to 7 times greater than plasma concentrations in cartilage and meniscus, and up to one hundred times greater than plasma concentrations in tendons.29 Topical analgesics are ideal among older adults with multiple comorbidities such as peptic ulcer disease and cardiovascular disease in which oral NSAIDs are relatively contraindicated.

Examples of topical analgesics include diclofenac, ketoprofen, ibuprofen, 4-5% lidocaine patch, EMLA cream, and capsaicin cream. Neuropathies, soft-tissue strains and sprains, contusions, burns, skin or leg ulcers, acute herpetic zoster, low back pain, osteoarthritis flares, and cancer-related pain are all painful conditions that may benefit from topical analgesics.28

OPIOIDS

Many patients who come to the ED have moderate to severe pain, as over the counter analgesics can manage most milder forms of pain at home. In the ED, commonly used oral opioids include oxycodone and hydrocodone, usually in combination with acetaminophen. Common parenteral opioids used in the ED include morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl.

Among older adults, consider reducing the initial dose to accommodate the physiologic changes associated with aging including muscle atrophy, volume depletion, reduced organ function, and drug clearance. In addition, frequently reassess and re-dose as needed to avoid undertreatment of pain while monitoring for adverse effects. Consider morphine (0.05-0.1 mg/kg IV or 4-6 mg fixed-dose PO) as first-line opioid analgesia for older adults in moderate to severe pain unresponsive to non-opioid oral analgesics. Alternatively, hydromorphone (0.5 mg IV with an early repeated-dose as needed) can be used. The "half and half" protocol of 0.5 mg IV hydromorphone followed by an optional repeated dose 15 minutes later of 0.5 mg IV hydromorphone based on patient's response to the question, "Do you want more pain medication?" has been shown to provide comparable analgesia to usual care but with less overall opioid use.30 If using oral opioids, reassessment should occur 20-30 minutes of analgesic administration.

Caution should be taken among older adults with renal dysfunction when using opioids with active metabolites that are reliant on renal clearance, such as morphine and hydromorphone).31 In such cases, consider fentanyl (0.5-1.0 mcg/kg IV) which is less reliant on renal clearance or lower the dose of morphine or hydromorphone.

ADJUNCT THERAPIES

Non-pharmacologic therapies should be employed when possible among older adults in order to limit systemic pharmacologic delivery and their potential adverse effects. In addition to alternating heat and cold applied to injured areas, the following adjuncts may be employed:

Nerve Blocks

Nerve blocks provide the advantage of a localized form of pain relief, improved door-to-analgesia timing, and lowered doses of analgesic medication.32-34 Nerve blocks using common anesthetics (eg, lidocaine, bupivacaine, ropivacaine) can be used as a stand-alone treatment for older adults, though optimally they are used as part of a multimodal analgesic regimen or as a bridge to further inpatient pain management.35 Ultrasound-guided femoral nerve blocks performed in the ED have been shown to provide adequate pain relief for older adults who present with acute hip fractures.34 Compared to other emergency procedures, nerve blocks are relatively easy to learn and can be effectively utilized at the residency level with proper training.36 Ultrasound-guidance provides further safety and efficacy in administering nerve block.37 See chapter on Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blocks for further discussion on how to perform these procedures.

Ketamine

Ketamine given at subdissociative doses (SDK, 0.1-0.3 mg/kg IV) has been shown to provide analgesic effect while preserving airway reflexes, spontaneous respiration, and cardiopulmonary stability among non-elderly patients.38 Among older adults, 0.3 mg/kg IV SDK over 15-minute slow infusion has been shown to result in analgesic efficacy comparable to morphine in the treatment of acute moderate/severe pain, though with an increased incidence of adverse events.39 Lower doses (0.1-0.3 mg/kg IV) given as a slow infusion may be considered as an analgesic adjunct among older patients unresponsive to first-line oral analgesics.

Drugs to Avoid In Older Adults in the ED

Skeletal muscle relaxants such as cyclobenzaprine, metaxalone, methocarbamol, carisoprodol, and orphenadrine are listed in the Beer's Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use due to their increased risk of dizziness, weakness, and fall risks.5 Though commonly prescribed in younger patients, caution should be reserved when prescribing these for older adults.

Tramadol is classified as an atypical opioid due to its weak mu-opioid receptor activity. Tramadol is metabolized by the liver (CYP3A4, CYP2D6) to O-desmethyltramadol (ODT, M1).40 Enzymatic allelic variability of CYP2D6 metabolism creates a varied response to tramadol. The active metabolites of tramadol are dependent on renal clearance and can result in toxicity among patients with renal disease and older adults with decreased renal function resulting in seizures, hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, and serotonin syndrome.5 For these reasons, tramadol should not be considered a first or even second line analgesic agent for use in the ED and at discharge.

Tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin, and pregabalin are generally the purview of the primary care physician or pain management specialist. These medications also act to potentiate opioid effects, worsen respiratory depression, and have sedating effects and so should be avoided among in older adults.5 As these medications often require an extended duration of use to optimize the therapeutic effect, they are not thought to be helpful during an acute ED visit.

Non-pharmacologic Adjuncts

Ice, heating pads, exercise (yoga, tai chi, walking), injections (eg, epidural, trigger point, etc) and massage therapy are commonly recommended outpatient non-pharmacologic treatments for most pain presentations and may be recommended for older adults at discharge. Other non-pharmacologic therapies including virtual reality (VR), cognitive-behavioral training, and acupuncture are also under investigation as future analgesic treatment options to limit acute and chronic pain pathology.

DISPOSITION RECOMMENDATIONS

Patients with severe pain may require a period of observation or full inpatient admission. Prior to ED discharge, it is important to review the patient’s home living situation, risks for repeated injuries, and ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL's), which also may result in the need for hospitalization despite the ability to manage the patient’s pain. It is also recommended to review the patient's current medications before starting a new analgesic in order to avoid drug-drug interactions. For patients requiring a short course of analgesics, acetaminophen, topical analgesics, and non-pharmacologic treatments are recommended. Advise patients to stay active and avoid bed rest which can be counterproductive and delay patients’ return to their usual activity. NSAIDs, when prescribed, should be given for a maximum of 3-5 days and ideally taken with food and then discontinued once pain ceases in order to avoid adverse effects.

Summary

Older adults present with pain pathologies complicated by a broad range of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variations due to physiologic changes of aging that require thoughtful and patient-tailored analgesic choices. Following a review of the patient's current medications, a number of non-opioid and opioid analgesics as well as non-pharmacological adjuncts may be considered to treat mild to severe pain. Lowered dose and frequent reassessments and redosing is recommended to avoid adverse effects. Consideration of the Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults will further assist in avoiding adverse complications.

References

- Gupta, D.K. and M.J. Avram, Rational opioid dosing in the elderly: dose and dosing interval when initiating opioid therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2012. 91(2): p. 339-43.

- Hwang, U. and T.F. Platts-Mills, Acute pain management in older adults in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med, 2013. 29(1): p. 151-64.

- Boss, G.R. and J.E. Seegmiller, Age-related physiological changes and their clinical significance. West J Med, 1981. 135(6): p. 434-40.

- Qato, D.M., et al., Changes in Prescription and Over-the-Counter Medication and Dietary Supplement Use Among Older Adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med, 2016. 176(4): p. 473-82.

- By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert, P., American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria(R) for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2019. 67(4): p. 674-694.

- Feldt, K.S., M.B. Ryden, and S. Miles, Treatment of pain in cognitively impaired compared with cognitively intact older patients with hip-fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc, 1998. 46(9): p. 1079-85.

- Cole, L.J., et al., Pain sensitivity and fMRI pain-related brain activity in Alzheimer's disease. Brain, 2006. 129(Pt 11): p. 2957-65.

- Spector, W.D., Mutter, R., Owens, P., Limcangco, R., Thirty-day, all-cause readmissions for elderly patients who have an injury-related inpatient stay. Medical care, 2012. 50(10): p. 863-869.

- Steinmiller, J., P. Routasalo, and T. Suominen, Older people in the emergency department: a literature review. Int J Older People Nurs, 2015. 10(4): p. 284-305.

- Davis, M.P., Srivastava, M., "Demographics Assessment and Management of Pain in the Elderly". Drugs & aging, 2003. 20(1): p. 23-57.

- American Geriatrics Society Panel on Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older, P., Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2009. 57(8): p. 1331-46.

- By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert, P., American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2015. 63(11): p. 2227-46.

- Chang, A.K., et al., Effect of a Single Dose of Oral Opioid and Nonopioid Analgesics on Acute Extremity Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 2017. 318(17): p. 1661-1667.

- Caldeira, D., et al., How safe is acetaminophen use in patients treated with vitamin K antagonists? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res, 2015. 135(1): p. 58-61.

- Seymour, R.A., P. Ward-Booth, and P.J. Kelly, Evaluation of different doses of soluble ibuprofen and ibuprofen tablets in postoperative dental pain. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1996. 34(1): p. 110-4.

- Motov, S., et al., Comparison of Intravenous Ketorolac at Three Single-Dose Regimens for Treating Acute Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med, 2017. 70(2): p. 177-184.

- Bailey, E., et al., Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2013(12): p. CD004624.

- Aalami, O.O., et al., Physiological features of aging persons. Arch Surg, 2003. 138(10): p. 1068-76.

- Pilotto, A., et al., Proton-pump inhibitors reduce the risk of uncomplicated peptic ulcer in elderly either acute or chronic users of aspirin/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2004. 20(10): p. 1091-7.

- American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Group on Use of, S. and D. Nonselective Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory, Recommendations for use of selective and nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an American College of Rheumatology white paper. Arthritis Rheum, 2008. 59(8): p. 1058-73.

- Danelich, I.M., et al., Safety of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in patients with cardiovascular disease. Pharmacotherapy, 2015. 35(5): p. 520-35.

- Gislason, G.H., et al., Risk of death or reinfarction associated with the use of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation, 2006. 113(25): p. 2906-13.

- Schjerning Olsen, A.M., et al., Duration of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and impact on risk of death and recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with prior myocardial infarction: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation, 2011. 123(20): p. 2226-35.

- Antman, E.M., et al., Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2007. 115(12): p. 1634-42.

- Meara, A.S. and L.S. Simon, Advice from professional societies: appropriate use of NSAIDs. Pain Med, 2013. 14 Suppl 1: p. S3-10.

- Wongrakpanich, S., et al., A Comprehensive Review of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use in The Elderly. Aging Dis, 2018. 9(1): p. 143-150.

- Coxib, et al., Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet, 2013. 382(9894): p. 769-79.

- Leppert, W., et al., Transdermal and Topical Drug Administration in the Treatment of Pain. Molecules, 2018. 23(3).

- McCarberg, B. and Y. D'Arcy, Options in topical therapies in the management of patients with acute pain. Postgrad Med, 2013. 125(4 Suppl 1): p. 19-24.

- Chang, A.K., et al., Randomized clinical trial of an intravenous hydromorphone titration protocol versus usual care for management of acute pain in older emergency department patients. Drugs Aging, 2013. 30(9): p. 747-54.

- Dean, M., Opioids in renal failure and dialysis patients. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2004. 28(5): p. 497-504.

- Johnson, B., et al., Door-to-block time: prioritizing acute pain management for femoral fractures in the ED. Am J Emerg Med, 2014. 32(7): p. 801-3.

- Wilson, C., Feeling Blocked? Another Pain Management Tool in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med, 2018.

- Beaudoin, F.L., et al., Ultrasound-guided femoral nerve blocks in elderly patients with hip fractures. Am J Emerg Med, 2010. 28(1): p. 76-81.

- Hards, M., et al. Efficacy of Prehospital Analgesia with Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block for Femoral Bone Fractures: A Systematic Review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2018. 33(3): p. 299-307.

- Akhtar, S., et al. A brief educational intervention is effective in teaching the femoral nerve block procedure to first-year emergency medicine residents. J Emerg Med. 2013. 45(5): p. 726-30.

- Neal JM. Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia and Patient Safety: Update of an Evidence-Based Analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016. 41(2): p. 195-204.

- Motov, S., et al. A prospective randomized, double-dummy trial comparing IV push low dose ketamine to short infusion of low dose ketamine for treatment of pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2017. 35(8): p. 1095-1100.

- Motov, S., et al. Intravenous subdissociative-dose ketamine versus morphine for acute geriatric pain in the Emergency Department: A randomized control trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2018.

- Smith, H.S., Opioid metabolism. Mayo Clin Proc, 2009. 84(7): p. 613-24.