Ch. 17 - Advanced Practice Providers in the ED

Muhammad Shareef, MD; Petrina L. Craine, MD; Andrew I. Bern, MD, FACEP

The United States continues to face an imbalance in supply and demand for physicians. Filling this void, the number of advanced practice providers entering the health workforce and the ED specifically has increased substantially in the past few decades.1 Nationwide, there were more than 248,000 licensed nurse practitioners (NPs) as of 20182,3 and 123,000 physician assistants (PAs) certified in 2017.4 Though NPs outnumber PAs nationally, within the emergency department, as of 2014, there were nearly double the number of PAs compared to NPs, at about 9,822 PAs vs. 4,523 NPs.5

As the population ages and drives health care demand ever higher, APPs will serve as part of the team-based solution.

Advanced Practice Provider Training

Although APPs have similar levels of autonomy in EDs (more specifically dictated by individual state laws and hospital bylaws), they take different training routes. PAs typically complete 2.5–3 year training programs involving about 1,000 classroom hours and roughly double the clinical rotation hours as compared to NPs. In contrast, NPs obtain a 2-year master’s degree in nursing after having completed nursing school, typically adding approximately 500 classroom hours and 500–700 more clinical hours after nursing school. While there has been an effort to require NPs to earn doctoral degrees in nursing, the provider shortage has slowed this initiative in some areas.6,7

As of 2017, there were approximately 11 different EM NP fellowship/residency programs and 42 accredited PA emergency medicine residency programs (“residency” and “fellowship” are interchangeable labels for PA/NP programs, in contrast to physician programs).8,9 The Accreditation Review Commission on Education for PAs (ARC-PA) used to accredit PA training programs but the process has been in abeyance for several years. The Society for EM PAs (SEMPA) has created postgraduate training standards as a framework that new and existing EMPA postgraduate programs could use to improve or create EMPA postgraduate programs.10 Physician Assistant residency programs range in length from 1–2 years, with most lasting 18 months. Many PA residencies are housed in institutions with EM residencies, and many integrate the didactic curricula so PAs join in resident educational conference, journal clubs, ICU and other clinical rotations, simulation, and in some cases a research requirement.11 The number of APP EM training programs is much lower than the current 240 EM residency programs that recruit nearly 2,000 newly minted emergency medicine residency trained physicians a year.12 In contrast, most NPs and PAs are not required to complete residency/fellowship programs to enter emergency medicine practice. However, with APP specialty organizations attempting to standardize training, there continues to be an overall growth in the numbers of NP and PA fellowship/residency programs, as well as a push toward completing advanced training after graduating from NP/PA school.

Advanced Practice Providers and the Emergency Medicine Workforce

Advanced practice providers, including NPs and PAs, make up about a quarter of the EM workforce and see about a fifth of ED visits. A cross-sectional study of Medicare data examining 58,641 EM clinicians found that 24.5% of these were composed of APPs.13 The proportion of ED patients seen by an APP has substantially increased over time. According to the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, APPs saw 5.5% of all ED patients in 1997, 12.7% in 2006, and 20.5% in 2015 (consisting of NPs [8.0%] or PAs [12.5%]).13 APPs see a range of acuity level patients, but most often staff high-volume, fast-track, or express care sections within EDs. Compared to physicians, APPs see more lower acuity patients, with only 11% of patients seen by APPs in the highest triage category.14

In addition to caring for a large and varied level of all ED patients, APPs have been working in more EDs and working more hours. According to surveys from the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance, the percent of EDs utilizing APPs ballooned from 23% in 2010 to 62% in 2016. Moreover, APPs are working more of the total hours available. In 2010, APPs worked 53% of physician staffing hours; by 2016 this number had risen to 64%.6 Looking ahead, APPs are projected to have continued workforce growth of about 30% between 2014 and 2024, a startling number that far outpaces the projection for physician growth.5,15 With ever-increasing ED volume and crowding, APPs are crucial to providing services in the ED and to the sustainability of the EM workforce.

Nonetheless, there is a perceived difference between NPs and PAs among emergency physicians: a poll revealed that EM physicians perceive NPs tend to use more resources as compared to PAs, and that APPs use more resources than physicians when seeing patients with similar emergency severity index levels.16 In addition, there was more interest in hiring younger, less-trained PAs as compared to NPs, with a possible reason cited as the clinical education for PAs was thought to be stronger than NPs.16 Although there are no robust studies to support such perceptions and the data is obscured by different state laws regarding APPs, it

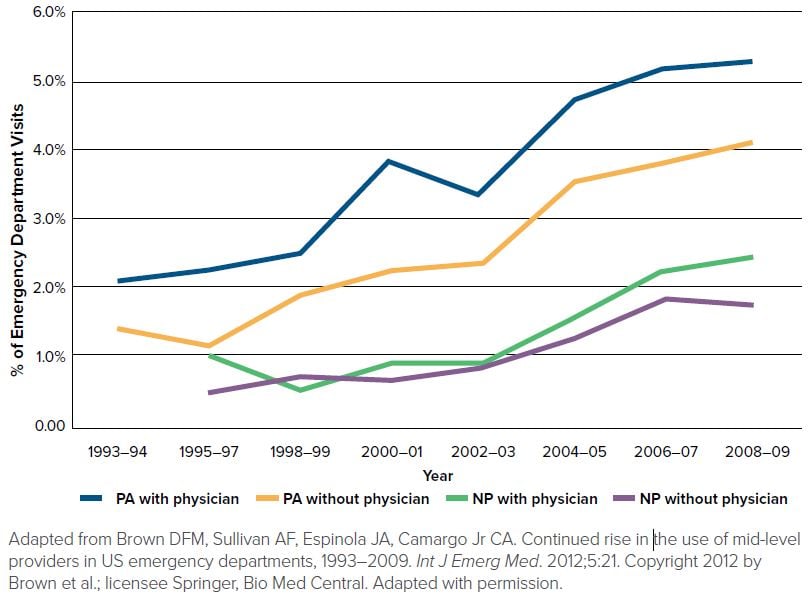

FIGURE 17.1. Trends in ED Visits

may partly explain differences in levels of physician oversight for APPs. In fact, from the NHAMCS respondents, only half who received care from a PA during an encounter also reported seeing a physician, as compared to two-thirds of those who received care from a NP who were also seen by an EM physician.13

Advanced Practice Providers and the Veterans Affairs

The health of vulnerable patient populations, such as the elderly and the underserved, are particularly sensitive to the negative effects of a physician shortage.15,17 One example of a medical system adapting to the increased needs of its population is the VA, through its use of telemedicine services and expanding the role and responsibilities of APPs.

The VA is the largest integrated health care system in the U.S. Since the 1990s it has used various strategies to coordinate and integrate medical care while attempting to control costs.18 In 2014, the VA was the subject of highly publicized criticism and scrutiny about long wait times for patient services. As also the largest employer of nursing providers, with nearly 6,000 advanced practice nurses available, the VA made a controversial decision to allow NPs “full practice authority” in their facilities. Thus, NPs at VA facilities can assess, diagnose, and treat (including prescribing medications) patients without direct supervision or mandatory collaboration from a physician.19 This federal permission for full practice was granted, despite conflicting with some states’ scope of practice laws.20 It is important to note that some ambiguity still exists, as prescribing authority for NPs at VA facilities can still be limited if a state has restricted its NPs from holding DEA registration that allows for the prescribing of controlled substances. Also, federal facilities have the right to opt out of the VA’s NP full practice designation, thus demonstrating further uncertainty.20,21 Some have argued that the VA’s decision could compromise the quality of care and thus potential health outcomes.22

Although controversial, there is little to no data to support that the VA’s decision would be dangerous for patients. Research on patient care outcomes from this change has not yet been explored, but previous studies on NP full practice authority and quality care suggest independent supervision of NPs is associated with non-inferior patient outcomes as well as decreases in hospital readmissions.23-25 Studies have shown that despite differences in training and clinical hours as compared to physicians, PAs and NPs provide safe, effective, and non-inferior care to patients.18,26-27 The VA states that expanding NP capabilities are essential to increasing its capacity to deliver “timely, efficient, effective, and safe” care.

The Practice of Advanced Practice Providers

Scope of practice is the regulatory way to guide the activities different medical professionals can perform. Although it is determined and governed by state laws, federal actors such as Congress, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Federal Trade Commission, provide influence. As scope of practice defines what a particular medical professional can and cannot do, it also influences reimbursement.17

Various “scope of practice” bills have been introduced over the years in state and federal legislatures. Although these bills greatly differ in specifics, most have featured proposals to expand the scope of practice for APPs, including requesting full practice authority.28 In response to some APPs efforts to expand their scope of practice, organized physician groups such as the AMA have supported legislation designed to oppose the expansion of non-physician medical providers scope of practice.29 A common message from physician groups is that unchecked non-physician expansion of practice not only threatens the collegial relationship between physicians and APPs but also ”threatens the health and safety of patients.”29 Although a bill addressing APP practice expansion has not yet been passed by Congress, in 2017, 37 scope of practice bills that expanded APP practice were enacted into law by nearly half of U.S. states.30

With so many physician and non-physician professionals in the health care system, there is potential for misrepresentation of credentials.31 Expansion of scope of practice for PAs and NPs, such as increased prescribing and procedural abilities, further independence from physician oversight, and more social recognition of authority conferred through the title of “doctor” from the completion of nonphysician doctorate programs (eg, “Doctor of Nursing”) has been implicated as a factor in not only fueling fraudulent efforts but also confusing patients.17 A study conducted by the AMA in 2014 showed that nearly 35% of patients believed a doctor of nursing practice was the same as a medical doctor.32

In 2015, the AMA expanded its efforts to define the scope of practice limits with its “physician-led team-based care” campaign. A core tenet of this campaign is in defining physicians as the leaders of health care teams for patients, arguing other providers are “indispensable” but “they cannot take the place of a fully trained physician.”33 The program is a complement to its “Truth in Advertising” campaign, an initiative to require state mandates for the proper identification and display of medical credentials of different medical professionals in an effort to prevent “confusing or misleading health care advertising that has the potential to put patient safety at risk.”32 Some APP organizations have opposed these efforts, calling them “unnecessary and inappropriate” redundancies to state requirements already in place.33 The AMA and other physician groups like ACEP continue to advocate for transparency about the different roles of APPs and limits on scope of practice.34

Advanced Practice Providers and Physician Oversight

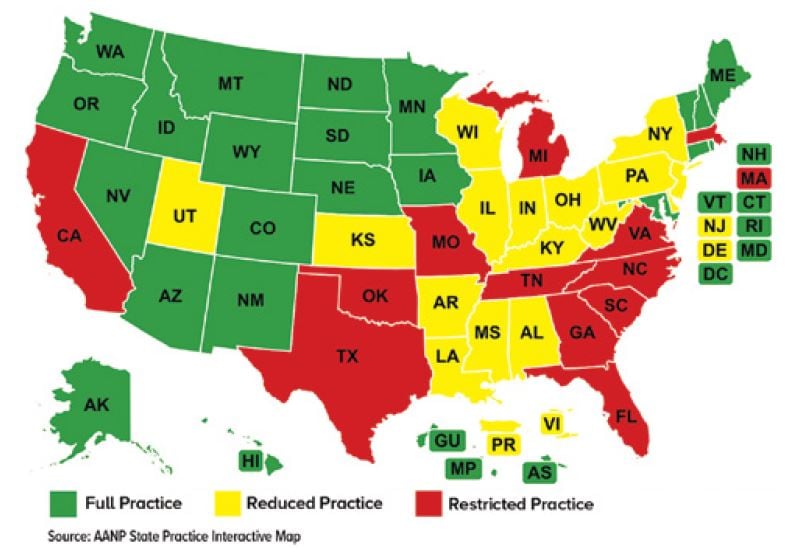

As scope of practice laws are different for each state, medical professionals are subjected to various rules. While physicians’ scope of practice has little variation between states,17 for APPs the differences can be astounding.35 Some practice alongside a physician, while others practice independently within the realm of their training, such as in express care/fast-track type settings where acuity is generally lower. Some states allow full practice for NPs without any physician oversight, while others employ significantly more limitations (Figure 17.2).36,37

Although PAs are required to practice under physician supervision in every state, the practical application of this mandate can vary.38 Some PAs practice with a mandate of a physician required to be on-site while others may only require a physician, who may be off-site, to sign off on PA medical documentation without physically interacting with the patient. Many states now allow the details of a PA’s scope to be decided at an institutional level, such as in an emergency department.39

Scope of practice law differences not only create implications for APP and physician liability but also affect a state’s medical workforce.35 For instance, states with fewer restrictions on PA and NP independence tend to have more APPs than actual physicians.15 With continued physician shortages, increasing health care spending, and dynamic changes in insurance coverage, the number of APPs primarily seeing ED patients will likely continue to increase, not only because of unmet need but also due to financial implications.40 APPs are generally paid less than physicians while providing patient care that maximizes ED efficiency and throughput, important components in maximizing hospital reimbursement from payers such as Medicare and Medicaid.41,42 Some research has shown that more APPs in the medical workforce results in substantial savings for health care systems and patients, without sacrificing the quality of care rendered.43-48

FIGURE 17.2. State Practice Environment for NPs

Advanced Practice Provider Organizations and Advocacy

With the increasing need and presence of APPs in EM, APPs have created organizations to represent and advocate for their roles in the ED, including SEMPA (founded in 1990), the Emergency Nurses Association (founded in 1970), and the American Academy of Emergency Nurse Practitioners (founded in 2014). These organizations advocate for a variety of initiatives, ranging from standardizing certification and defining scope of practice guidelines to lobbying for increased independence from physicians. Though APPs are not eligible for ACEP membership, ACEP and SEMPA have had a cooperative and productive relationship over the years. In fact, SEMPA contracts with ACEP to manage daily operations, conference planning, and other organizational functions. As teambased health care becomes the norm, mutual understanding, shared aims and collaboration between health professionals of varying training backgrounds will lead to stronger health care for all our patients.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- Increase your knowledge about federal and state laws governing the scope of practice of APPs where you practice.

- Advocate for the continued importance of physicians as health care team leaders in emergency medicine.

- Work with government representatives and APP organizations to promote a culture of transparency in providing patients accurate information about provider’s credentials and roles.