Ch. 20 - Corporate Practice of [Emergency] Medicine

Jordan M. Warchol, MD, MPH

The Corporate Practice of Medicine doctrine (CPOM)is the term used for the general principle that limits the practice of medicine to licensed physicians and prohibits corporations from practicing medicine or directly employing a physician. Most, but not all, states have laws prohibiting the corporate practice of medicine. These laws can limit or prohibit non-physicians from owning, investing in, or otherwise controlling medical practices. Over the years since they were enacted, these policies have been shaped by legislation, regulation, case law (decisions within the court system), and the opinions of state attorneys general.1

The corporate practice of medicine is a complex topic that affects many aspects of the life and practice of the emergency physician.

Exceptions to CPOM are relatively common. All states exempt professional corporations when they are groups formed by physicians for the purpose of rendering care. However, there are varying degrees to which states specify the structure of these corporations, such as who is able to hold shares or serve on the board of directors.2 Hospitals are also exempted in many states, given the joint interest between the physician and the hospital in the care of the patient. In these arrangements, there is often stipulation that the employer not interfere with or attempt to control the independent medical judgement of the physician. Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), which collect fees on a per-patient basis known as capitated payments, are exempted by federal statute that preempts state laws relating to CPOM.3 Conversely, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are subject to state laws and therefore not exempt from CPOM.4

History

Since its inception in the early 20th century, CPOM has been instrumental in shaping the U.S. health care landscape. CPOM is cited as the impetus for the separation of Medicare Part A (covering hospitalizations) and Part B (covering physician fees), based on the prohibition of “fee-splitting.” The AMA Code of Medical Ethics defines fee-splitting as “payment by or to a physician or health care institution solely for referral of a patient.”5 By paying physicians separately from the hospitals in which patients were cared for, such fee-splitting could be avoided.

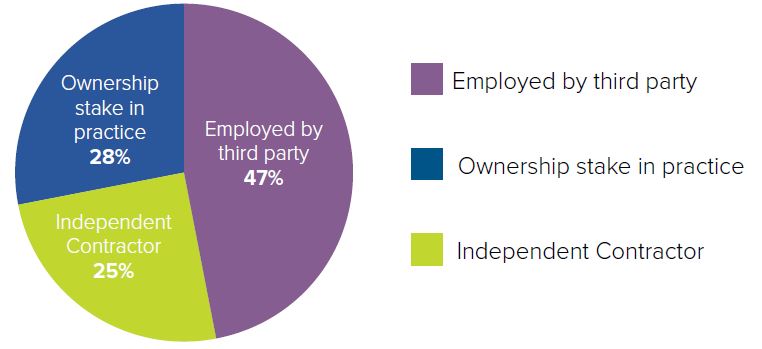

However, as more physicians are employed by hospitals, this split is increasingly artificial. In 2016, the percentage of physicians who do not have ownership in their practice topped 50% for the first time.6 This percentage can vary greatly depending on the specialty, age, and gender of a physician. Many emergency physicians (47.3%) are employed, with 27.9% having an ownership stake in their practice and 24.8% practicing as independent contractors.6 It is not clear what effect employment has on practice autonomy. A 2014 study found that 68.2% of employed physicians indicated that their ability to make the best decisions for patients had some or many limitations, compared to 70.6% of physician owners.7

FIGURE 20.1. Emergency Physician Employment Landscape

Physician Autonomy and CPOM

CPOM has important ramifications on the corporate structure of physician practices and the prevention of the commercialization of medicine. The central tenet of CPOM is to protect physician autonomy. The ability of a physician to make clinical decisions independent of the influence of their employer is essential to their ability to exercise independent medical judgement. This is especially important when the fiduciary obligation of a corporation to its shareholders does not align with the physician’s obligation to patients.

Maintaining physician autonomy in clinical decision-making is critical to the patient-physician relationship and to optimizing care. Still, the degree of autonomy physicians have in other aspects of their practice also influences the clinical setting and thus the treatment of patients. The following are just a few of the ways in which variations in autonomy may impact an emergency physician’s day-to-day practice.

Physician Staffing8,9

Few decisions impact an emergency physician’s practice more than how a department is staffed. Both the length of shifts and the type of provider coverage (single physician vs. multiple physicians vs. a combination of physicians and APPs) have a significant impact on the physician and patient experience in the ED. Department staffing directly affects the number of patients per hour a physician sees, and, consequently, how much time the physician may spend with each patient. Staffing also influences quality metrics, such as door-to-doctor or door-to-discharge times,10 which may become more important as physician payment methodologies move away from volume and toward value. Inadequate physician staffing can have a significant negative impact on physician satisfaction and the quality of patient care.

Use of Advanced Practice Providers

The use of APPs to staff an ED is another important decision impacting emergency physician autonomy and patient care. As APPs practice under the license of an emergency physician,11 their supervision not only places greater demands on the physician, but also exposes him/her to increased legal liability. Emergency physicians may not always be adequately compensated for these increased supervisory demands and legal liabilities.

Open-Book vs. Closed-Book Billing

In an “open-book” practice, the emergency physician can review what a patient is being billed for the services provided. When a practice is “closed-book,” the physician does not know what a patient is being billed for emergency care. Without knowing what patients are being billed, it is difficult for a physician to monitor overbilling to prevent fraud.12 Closed-book billing also limits the physician from assuring their compensation is commensurate with what a patient is being charged for those services. While often associated with physician practice management companies (PPMCs), closed-book billing can also be found in private group practices and employed-physician situations, and should be considered when evaluating a potential position.

Non-Compete Clauses

With increasing consolidation in groups, hospitals, and health systems, overly restrictive non-compete clauses can significantly impact a physician’s ability to find a new position if current employment ends. The inability of a physician to relocate can have a significant impact on their autonomy to practice where and when they choose. Emergency physicians should be careful when considering any contract with a non-compete clause and consider consulting legal counsel, as these clauses are often technically complex.

Due Process13

The concept of due process, broadly summarized as fairness in dealings, is codified in the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. However, due process in that instance is only guaranteed in dealings with the federal government. The Supreme Court has also ruled that due process applies to medical licensure, and therefore a state must abide by due process if it wants to pursue any action against a physician’s license. Due process is generally not applicable to hospital employment or privileges in the same way it applies to governmental actions.

Medical staff bylaws often describe a process by which termination of a physician from the medical staff must proceed. This may protect a physician from undue dismissal, but it is important to note that these protections may be waived by an employer, with or without the physician’s direct knowledge. A hospital may require that a physician contract contain a waiver of any due process afforded to the physician by medical staff bylaws. This can also be enforced by the hospital through its contract with a private group practice or PPMC instead of directly in a physician contract. Emergency physicians are combatting this practice through ACEP-supported federal legislation introduced in the 115th Congress that seeks to eliminate the ability of a third-party contract to waive a physician’s due process rights.14,15 It is important to thoroughly explore one’s due process rights as an employee or independent contractor before signing a contract.

Emergency Medicine Practice Models

Emergency medicine has a unique relationship with the principles of CPOM. Foremost, the solo physician practice model found in many specialties is impossible in emergency medicine because of the nature of the specialty. Emergency physicians also do not have a specific panel of patients for whom they are responsible, making independent contracting more feasible than for many specialties. There are many ways in which an emergency physician practice can be structured, and each has its own CPOM considerations.

Hospital or Academic Practices

Some emergency physicians are employees of a hospital or academic medical center. As employees, these physicians usually enjoy guaranteed salaries and benefits, and also avoid many of the administrative burdens of private practice. These practice arrangements often include physicians in multiple specialties.

Private Practice Groups

The spectrum of private practice ranges from a handful of physicians covering a single emergency department to group practices including dozens of physicians covering multiple hospitals. These private practice groups are typically organized as partnerships or limited liability companies in which the partners or shareholders are all emergency physicians. Physicians in private practice groups often share increased administrative burdens or hire outside services to take care of administrative functions, such as billing and collections.

While a private practice group may have salaried physician employees who are not partners or shareholders, the expectation is often that physician employees will eventually become partners or shareholders. The extent to and the time frame in which these employees become partners or shareholders is an important consideration for any physician joining such a practice.

Physician Practice Management Companies

In PPMCs, a corporate entity contracts with multiple hospitals to provide physicians to staff the EDs. The PPMC often handles billing, scheduling, recordkeeping, liability insurance, and other important (but often cumbersome) administrative tasks. It can also provide educational support, leadership training, and other advancement opportunities for physicians, but it cannot directly employ physicians or provide clinical care.

While physician input may be sought by a PPMC, its policies are ultimately determined by corporate management, which may or may not include physicians. Likewise, whether publicly or privately owned, a PPMC’s profits accrue to its shareholders. For these reasons, among others, PPMCs have been a controversial aspect of emergency medicine for decades.

The forces in the health care system that have led to the proliferation of PPMCs is not altogether different than the forces that have driven more physicians to an employed practice. Ensuring adequate payment for the services one provides continues to become more complex, with mandated quality metrics, new payment arrangement schemes such as ACOs, and the move to value-based reimbursement. Physicians have also cited a lack of training on how to run a practice as a deterrent16 to pursuing ownership of a practice.

As the PPMC industry is estimated to have contracts with more than 50% of the emergency departments in the U.S.,17 the role of PPMCs in the practice of emergency medicine and the protection of physician autonomy are important issues for the specialty as a whole and physicians considering a PPMC arrangement in particular.

The corporate practice of medicine is a complex topic that affects many aspects of the life and practice of the emergency physician. This must be an essential consideration when one is deciding how and where to care for patients. Information regarding contracts for emergency physicians is available on the EMRA website at https://www.emra.org/residents-fellows/career-planning/contracts, including discussion of various practice arrangements and tips for negotiating the best contract for you.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- Advocate for the protection of provider autonomy, keeping in mind concerns regarding cost and quality improvement. This could include contacting your lawmakers about legislation protecting emergency physician due process rights (such as H.R. 6372 from the 115th Congress).

- Educate yourself about the changes in the practice landscape such as employment versus private practice, the increasing utilization of PPMCs, and basics of contracts; determine what arrangement will work best for you.

- Know what safeguards are provided at the local and state level to protect yourautonomous decision-making.