Ch. 4 - The Impact Of EMTALA

William (B.G.) TenBrink, MD; Eileen O'Sullivan, MB BCh BAO;Ramnik Dhaliwal, MD, JD; Kenneth Dodd, MD

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act was originally enacted to protect patients from being inappropriately transferred or denied emergency care because of their insurance status or ability to pay.1 It has become the basis of the safety net of the American health care system.2 However, EMTALA has no funding mechanism, and the annual direct costs to physicians from uncompensated care provided under EMTALA are estimated to be $4.2 billion.3 The law has helped to shape the modern emergency care system, but it has become the focus of increasing scrutiny.

The purpose of EMTALA is to ensure equal treatment for any person seeking emergency care, but the law is under constant threat.

The Law

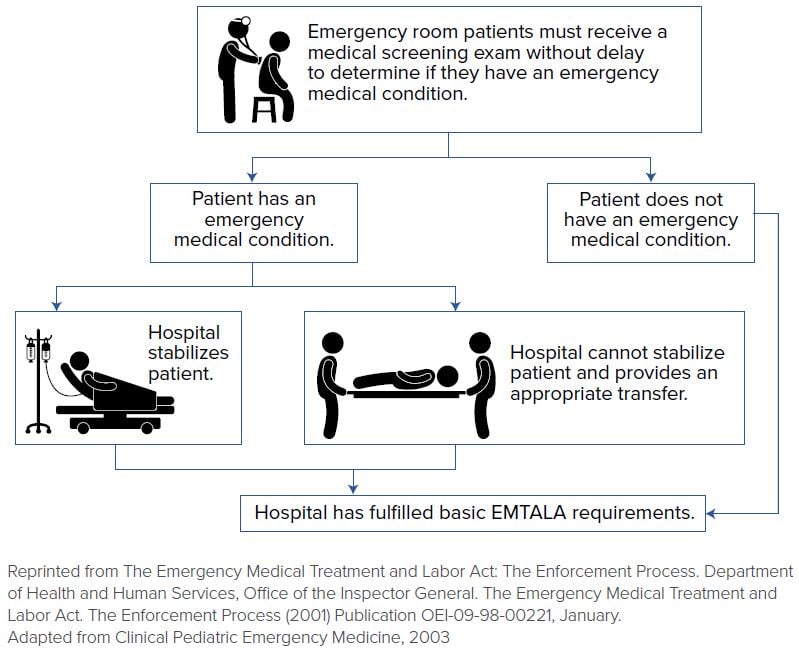

In 1986, EMTALA went into effect as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act (COBRA) of 1985.4 It established 3 main obligations on the part of all hospitals that receive Medicare funding and maintain an emergency department:5,6

- For any person who comes to a hospital emergency department, the hospital must provide for an appropriate medical screening examination… to determine whether or not an emergency medical condition exists.

- If an emergency medical condition exists, the hospital must stabilize the medical condition within its facilities or initiate an appropriate transfer to a facility capable of treating the patient.

- Hospitals with more specialized capabilities are obligated to accept appropriate transfers of patients if they have the capacity to treat the patients.

Under EMTALA, these criteria must be met regardless of insurance status or ability to pay, and investigation of a patient’s financial status may not delay these basic obligations.7 EMTALA compliance is regulated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

In 2003, HHS broadened the definition of a patient presenting to an ED to include those arriving on a “hospital campus,”8 defined as the physical area up to 250 yards from the main hospital building, including parking lots, sidewalks, administrative entrances, and areas that may bypass the emergency department, such as labor and delivery. Outpatient treatment areas located at satellite facilities that do not provide emergency services, such as walk-in clinics and urgent care facilities, do not fall under the umbrella of EMTALA law. The same ruling iterated that EMTALA does not apply to the inpatient setting,8 and this has been upheld multiple times.9

Medical Screening Examinations

Any person who arrives at an emergency department for examination or treatment for a medical condition must be provided a medical screening examination (MSE) “within the hospital’s capability of the hospital’s emergency department, including ancillary services routinely available… to determine whether or not an underlying emergency medical condition exists.”8-13 Provisions allow a hospital’s board of directors to designate certain non-physician members of their health care team to perform the MSE.5 Generally, the MSE is performed by a physician, an advanced practice provider, or a nurse. The triage process alone does not meet the requirement of the MSE.8 The exam must be of sufficient detail to uncover an underlying emergency medical condition (EMC) after a good faith effort.

The Stabilization Requirement

Like the screening requirement, the stabilization requirement applies to all Medicare-participating hospitals with dedicated EDs. This requirement must be fulfilled only if an EMC is discovered on the MSE.14 The definition of an EMC, by statute, is:15

“a medical condition manifesting itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity (including severe pain) such that the absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably be expected to result in placing the individual’s health (or the health of an unborn child) in serious jeopardy, serious impairment to bodily functions, or serious dysfunction of bodily organs; or with respect to a pregnant woman who is having contractions that there is inadequate time to effect a safe transfer to another hospital before delivery, or that transfer may pose a threat to the health or safety of the woman or the unborn child.”

Hence, an individual is considered stabilized when there is a reasonable assurance that no material deterioration would result from transfer or discharge from the hospital or, in the case of women in labor, after delivery of the child and placenta.16 Neither the physician nor the hospital have ongoing EMTALA obligations after a patient has been stabilized.

Under the stabilization requirement, if a hospital performed an adequate MSE but failed to accurately detect an individual’s EMC, the hospital may not have violated EMTALA’s provisions — even if they released the patient without adequate treatment.17 The hospital still may be civilly liable to the individual, however, based upon state medical malpractice law, if the failure to detect an EMC was due to negligence during the screening exam.18 EMTALA applies when there was actual or effective failure to provide the MSE,19 or if there is discrimination, whereas a malpractice suit may enter on a physician’s failure to reasonably recognize or act upon certain clinical findings.

FIGURE 4.1. Basic EMTALA Requirements

Appropriate Transfers

EMTALA requires a hospital to provide an “appropriate transfer” to another medical facility if a higher level of care or specialized treatment is necessary to stabilize a patient. The receiving hospital must accept such a transfer when it can provide these services, regardless of a patient’s insurance status or ability to pay. At that point, both hospitals are subject to EMTALA requirements. Ultimately, the patient may be transferred only if a physician certifies that the medical benefits expected from the transfer outweigh the risks; or if a patient makes a request in writing after being informed of the risks and benefits associated with the transfer. In either case, all of the following also must apply:4

- The patient has been treated and stabilized as far as possible within the capabilities of the transferring hospital.

- The transferring hospital must continue providing care in route, with the appropriate personnel and medical equipment to minimize risk.

- The receiving hospital has been contacted and agrees to accept the transfer.

- The receiving hospital has the facilities, personnel and equipment to provide necessary treatment.

- Copies of the medical records accompany the patient.

According to statute, a patient is considered stable if the treating physician determines no material deterioration should occur during transfer between facilities. Receiving hospitals must report perceived violations of the “appropriate transfer” clause in EMTALA to HHS, CMS, or an appropriate state agency. Unanticipated adverse outcomes or deterioration do not typically constitute an EMTALA violation.4 Most hospitals include EMTALA language in transfer forms to ensure compliance with the requirements.

Interestingly, 42 CFR Part 4896 iterates that this law does not apply to transfers of inpatients. An exception is that a hospital or physician can be penalized if bad faith is demonstrated. For example, a patient is admitted in an unstable condition for the sole purpose of transferring them.6 Similarly, transfer obligations of hospitals with specialized capabilities also cease upon admission.

The Penalties

An EMTALA violation may result in termination of a hospital’s or physician’s Medicare Provider Agreement in extreme circumstances where there are gross or repeated violations of EMTALA.21 More commonly, penalties include fines to the hospital and individual physician. The Office of Inspector General (OIG) more than doubled the potential civil monetary penalty (CMP) for violations of EMTALA to $104,826, per violation.20,21 In addition to CMPs, receiving facilities may sue transferring hospitals to recover damages and fiscal losses suffered as a result of an inappropriate transfer.

A recent analysis22 found that less than 8% of cases investigated by CMS resulted in settlements;23 97% of these were penalties against hospitals, and most complaints related to reported improper MSEs. Treating or transferring hospitals can be found liable when their providers or policies cause EMTALA violations. Hospitals are not considered in violation of EMTALA if a patient refuses the MSE or stabilizing treatment so long as there was no coercion and all reasonable measures are taken to secure documentation from the patient or someone acting on their behalf.

Investigation of EMTALA violations is initiated by complaints, and EMTALA does include “whistleblower” protections for hospital personnel who report violations. There is a burden of proof on the accuser and this burden of proving a claim can be a reason a safety-net hospital, for example, may decide not to pursue an EMTALA complaint. A receiving hospital can be subject to a misdemeanor charge, however, by failing to disclose a violation. The OIG for HHS and CMS are responsible for such investigations; currently, there is a 2-year statute of limitations for civil enforcement of any violation.

Expanding Patient Population and Burden

Although EMTALA was intended to support the rights of the indigent patient, there have been unanticipated consequences of the law. These consequences include heavy monetary implications for those hospitals that constitute the safety net for this patient population and provide a disproportionate volume of uncompensated care. With a growing number of ED visits and a large proportion of uninsured patients, the system has seen overcrowding compounding this lack of financial support.24 For many smaller and urban hospitals, this burden has been so great as to cause closure.25 From 1991–2011, there was a loss of 647 EDs (12.7%), nationwide.26 On-call physician specialists who fail to come to the emergency department after having been called by an emergency physician can be found in violation of EMTALA.27 This obligation is felt to be a contributor to the decline in available on-call specialty services to EDs, in recent years.28

Emergency physicians have benefited from securing some compensation under the ACA from the millions of newly insured patients who would have previously received uncompensated care, under EMTALA. Still, the ACA does not directly address EMTALA-related care, and emergency physicians continue to provide uncompensated care to the 28 million Americans who remain uninsured. Furthermore, most of the expanded coverage was in Medicaid payments that are generally not felt to cover the actual cost of care.

The Prudent Layperson Standard29 has provided a great deal of protection for reimbursement of care provided under EMTALA. This is codified in federal law30 and obligates health insurance companies to cover visits based on the patient’s presenting symptoms, not the final diagnosis. Recently, Anthem Blue Cross/Blue Shield (BCBS) has put forth a policy in multiple states by which they retrospectively deny coverage to patients who are ultimately found to have nonurgent conditions, thus making the patient financially responsible for the visit. ACEP continues to fight this policy as it threatens to disincentivize patients from seeking necessary care out of fear of financial penalty.

EMTALA and Diversion

The MSE can occur at multiple potential sites in an ED, such as triage, an exam room, stabilization or resuscitation bays, or a lower acuity urgent care/fast track module. As long as the screening and stabilization occur within the bounds of the ED, no further regulations exist.

Should a hospital desire to move the patient to a different location to complete screening and stabilization, several criteria must be met. A “bona fide medical reason” for the move must exist, as well as standard criteria such that “all persons with the same medical condition are moved in such circumstances…”31 These criteria, for example, allow moving actively laboring patients from the ED to Labor and Delivery, and can be used to otherwise move patients to another location in the hospital for a MSE provided all other elements of their care continue to comply with EMTALA. CMS specifically states these provisions do not allow a patient to be moved off-site, and that the patient must be accompanied by appropriate medical personnel - a patient cannot walk themselves.31 EMTALA risk exists if patients are found to be moved, for example, to an urgent care center outside of the ED while comparable patients are evaluated in the ED, if non-qualified providers conduct the MSE, or on top of traditional tort liability if an urgent condition is missed on the MSE.22,32-33

In a 2018 case, Friedrich v. South County Hospital Healthcare, hospital-owned urgent care centers separate from the main hospital campus were found to be included under this definition.34 Although EMTALA is administrated regionally, this precedent suggests that diversion of patients to an urgent care center for evaluation before they reach a full ED can carry increased EMTALA risk to both the provider as well as the health care system operating said center.

As long as the MSE is occurring within the ED, by providers who have been designated by hospital policy and bylaw to conduct screening exams, there appears to be little EMTALA risk in completing the evaluation in a fast track/urgent care/triage treatment zone that is part of the hospital’s ED. Conducting an MSE for potentially life-threatening concerns outside of the ED confers increased risk both to the patient as well as the provider.

Liability Reform

Emergency physicians and our on-call specialist colleagues uniquely care for patients with serious illnesses and injuries, with limited time and information. In these circumstances, the standard of care this provider can achieve is dependent on the circumstances of that encounter. It is felt by most emergency practitioners that while providing EMTALA-mandated care, these conditions of practice deserve special consideration and additional liability protections.

At the federal level, ACEP has repeatedly helped to introduce legislation addressing these liability issues. The most recent piece of legislation, H.R. 548, the “Health Care Safety Net Enhancement Act of 2017,” was introduced in January 2017 by Rep. Charlie Dent (R-PA). In its current form, this would provide temporary protections to emergency and on-call physicians, under the Federal Tort Claims Act,35-36 effectively considering those providers as federal employees with “sovereign immunity” when they are providing EMTALA-services. This legislation is an addendum to the Public Health Service Act. Under this proposed legislation, protections cease once patients are determined not to have emergency medical conditions or the emergency conditions are stabilized.

Repeal of EMTALA

The U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) published an investigative report in 2001,37 in response to concerns from the medical community that this legislation was excessively burdensome.38 This report discussed the role that EMTALAhas to play in uncompensated care, overcrowding and delays due to patients seeking non-urgent services. They also highlighted the many other factors that promote these issues, such as lack of access to care and increases in ED visits.

In October 2017, the House Budget Committee Chairwoman Rep. Diane Black (R-TN), a registered nurse, suggested during a television interview that EMTALA is in large part to blame for rising health care costs, and mentioned repeal. She argued that this law has taken away the ability for a provider to advise a patient when “an emergency room is not the proper place [for their evaluation].” ACEP continues to support EMTALA and rejected this assertion, given that uncompensated care in EDs amounts to less than 1% of the entire health care budget39-41 and that there exists good evidence that the vast majority of ED visits are “unavoidable.”42-43

WHAT’S THE ASK?

The purpose of EMTALA is to ensure equal treatment for any person seeking emergency care, but the law is under constant threat. Effective advocacy includes:

- Understanding the requirements for medical screening, stabilization and treatment.

- Recognizing threats to patient care from policies that potentially violate EMTALA through inappropriate diversion or transfers.

- Advocating for support for providers of EMTALA-related unfunded care.