Ch. 5 - Crowding and Boarding

Kathleen Y. Li, MD; Ramu Kharel, MD, MPH; Jessica Best, MD

Boarding patients in the ED has become routine in many hospitals in the United States. Younger emergency physicians may never work in an ED that does not struggle with boarding and crowding, as departments face higher volumes and more critically ill patients. The result is congestion not only in the ED but also on the inpatient hospital floors and critical care units. There are solutions to help solve issues with boarding and crowding and standards for transit through the health care system.

Boarding and crowding is common in emergency care, but it does not have to be. It is critical that physicians advocate for an efficient work environment that allows them to provide the care patients need.

What is ED Crowding?

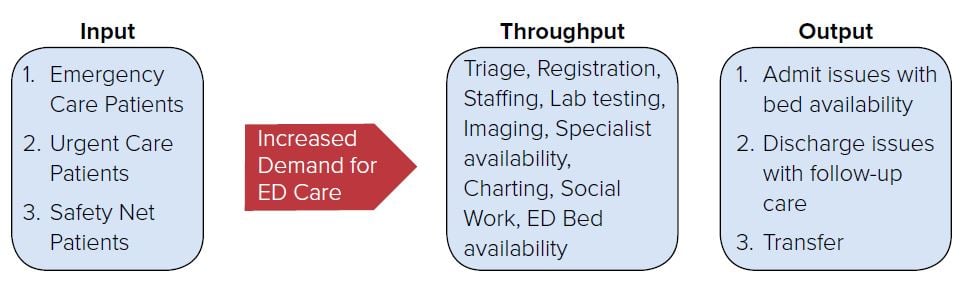

A 2014 Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on ED policy considerations defined ED crowding as “a situation in which the need for services exceeds an ED’s capacity to provide these services.” A number of factors contribute to crowding, from more patients coming to the ED either due to a lack of access to other forms of care, to inefficient ED processes or inadequate staffing, and a short supply of inpatient beds. The “input-throughput-output” model of crowding can be useful in identifying factors that contribute to or relieve ED crowding (see Figure 5.1). ED crowding results in problems such as long wait times, longer ED lengths-of-stay, and ambulance diversions, among others.

FIGURE 5.1. Input-Throughput-Output Model

Impact of Crowding on Patient Care

Crowding adversely affects patient care in a number of ways. Most important, it can delay care for patients presenting with time-sensitive conditions. In one study of patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome, increased crowding was associated with a delay of a median of 23 minutes in door-to-needle time in STEMI.1 ED crowding has also been associated with longer time to imaging in acute stroke2 and poorer performance on sepsis measures such as time to fluid and antibiotic administration.3

In addition, crowding can result in delays in the evaluation of patients by a doctor for a potentially emergent condition. Ambulance diversions increase patient transport times and long wait times cause more patients to leave without being seen. As the health care system backs up with crowding, the patients are displaced sicker and less differentiated into the least monitored location in the health system, the waiting room. With wait times in some large institutions longer than a day, the ability to recognize severe disease can be challenging and result in undiagnosed disasters.

- ● In 2017 at Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx, a patient went into a coma after waiting 9 hours in the waiting room. His chief complaint was assault; he was punched in the face, then fell to the ground. He ultimately died from an intracranial hemorrhage.4

- ● In 2008 at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, a patient was awaiting psychiatric placement when she collapsed in the holding area. There was a delay in recognition and resuscitation for the woman, who ultimately died.5

These incidents are just a few examples of what occurs in EDs with very large volumes of patients that struggle with crowding, boarding, and long ED wait times.

Health Care System’s Effect on Crowding

In the current health care system, emergency departments are responsible for more than just emergency care. Along with the original purpose of stabilizing seriously ill or injured patients, EDs are increasingly relied upon to fill the gaps in the overall health system. EDs are major providers for safety net care (for underserved populations), after-hours care, and acute exacerbation of chronic health issues. According to an AAMC report, there will be shortage of up to 43,000 PCPs by 2030.6 The significant gap in the supply and demand of primary and behavioral health care providers has added to the workload of emergency departments around the country as patients are unable to get care from their PCPs for acute exacerbations of chronic problems.

Despite speculations that implementation of the ACA would decrease ED visits, there has been a steady increase in ED utilization every year. Per H-CUP data from 2006–2015, rate of ED visits reached a 10-year high in 2015 for all age groups.7 Since the ACA’s enactment, the type of payer visiting the ED has changed, but the number of visits continued to rise in both Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states.8 Despite increasing use of HDHPs, threats to the Prudent Layperson standard, and other challenges in the current health care system, there does not appear to be a significant event that will result in the reduced utilization of emergency services anytime soon.

Boarding Causes Crowding

Although many factors contribute to ED crowding, boarding is the primary cause. According to the Joint Commission, boarding is defined as the “practice of holding patients in the emergency department or another temporary location after the decision to admit or transfer has been made.”9 Though it is not an accreditation requirement, current recommendations by the commission say boarding should not exceed 4 hours.9 Boarding in some institutions has become so common that inpatient nurses come to the ED to care for admitted-butboarded patients.

The demands of boarded patients directly compete with the time required to care for other patients in the ED. By their nature, boarded patients are some of the sickest patients in the ED (hence requiring inpatient admission), and demand ED resources frequently. This in turn exacerbates crowding because resources are delayed or unavailable for other emergencies presenting to the ED. For instance, compliance with sepsis bundles decreases, there is delay in administration of antibiotics, management of analgesia is poor for patients in severe pain. Additionally, boarded patients have poor outcomes with increased mortality rate and increase length of stay in hospital. Increasing boarding time has also been associated with a greater number of medical errors and increased patient dissatisfaction.

Potential Solutions to ED Overcrowding

The ACEP Emergency Medicine Practice Committee has put forth guidelines to address overcrowding.10 The guidelines focus on modifying input, throughput, and output of patients from the ED.

Solution #1 Modifying Input of Patients into the ED

A large influx of patients into the ED can increase wait times, prompting more patients to leave without being seen. However, there are ways to decrease traffic by diverting patients who may not require emergency care.

Some solutions to divert patient flow include posting ED wait times or allowing patients to make an appointment in the ED. Knowing the expected wait time may help patients make a better decision as to whether their condition is emergent, and if they can be seen in their outpatient clinic or alternative care site.11 By making ED appointments, a patient can be placed in a time slot where it will be predictably slower and their wait time will likely be less.

Access to primary care represents one key hurdle. A national study in Britain found that 26% of ED visits were due to an inability to obtain an appointment with a primary care physician.12 Another study found that by creating a clinic for their homeless population in Chicago, one hospital was able to reduce ED visits by 24%.13 With a growing number of patients without health insurance, creation of clinics for uninsured individuals may be necessary.

Utilization of alternative care sites including urgent cares and freestanding emergency departments can potentially help decrease the inflow of patients. Urgent care sites provide a less expensive alternative to the ED, and in some studies as much as 37% of patients presenting to an ED may be triaged as appropriate to be treated in non-ED settings such as urgent care if timely care can be provided.14 Free-standing emergency departments have allowed for more access to care for a subgroup of the population.15 Telemedicine, which can take the form of emails, phone calls, or web-based chats, also provides an alternative site of care.16

Solution #2 Increasing Throughput in the ED

Throughput in the ED starts at registration and continues to triage, provider care, testing, and finally disposition. There are ways to streamline these processes and allow treatment to start prior to the provider seeing the patient. In addition, there are ways to design the department to move patients

more quickly through lower acuity areas and decrease lab turnaround time by using point of care testing. The provider can be more efficient with charting by using effective EHR software or employing scribes. Dispositions can be sped up by the aid of social workers or case managers for complex care patients.

Patients may be able to hasten their own triage process by registering with a kiosk in the ED.17 Lower acuity patients can also pre-register at home prior to coming to the ED. Placing a provider in triage allows for the patient to be seen quickly on arrival, and formation of a treatment plan can be initiated and potentially implemented.17 If a provider cannot be in triage, nurses can start standing orders for patients with common ED complaints or those who may require simple imaging.

Split-flow models split patients into 2 categories: high and low acuity. The patients may be separated into another area frequently called a fast track. This area may be staffed by advanced practice providers who see lower acuity patients who need minimal resources. Split-flow models and fast tracks have proven to increase patient throughput.18 In addition to the fast track, other initiatives can help form a disposition faster: point of care testing in the ED and hiring an ED radiologist.19,20

For the provider, charting can be daunting when trying to move a heavy volume of patients through the department. Patients seen per hour by a provider was found to be increased with the use of a scribe.21,22 In addition, EHRs provide quick access to test ordering, information from prior admissions, and test results.23

Even with the most streamlined triage, provider care, and testing turnaround time, the patient may still be held up in the department because of social factors such as follow-up care, housing, or care for the mentally ill. Case managers and social workers can be helpful in coordinating care for high

utilizer and psychiatric patients.24,25 They can help with home consults and placement of patients outside of the hospital. Community health care providers who visit patients in their homes have helped to decreased ED visits from these patients.26

Solution #3 Increasing Output from the ED

Moving patients out of the ED more efficiently seems like an obvious solution to increase the number of beds available in the ED. If more beds cannot be created, then solutions must focus on effective output from the ED.

The critically ill patients who will be admitted will take the most time to work up and disposition to the floor or ICU. This will cause a backup with lower acuity patients in the waiting room if all beds are full. The military uses reverse triage to identify lower acuity patients, treat them, and discharge them quickly to get them back to battle. This approach could help free up space in the ED waiting room and treatment rooms.27 If the more critical patients must be seen immediately, then the ED should move them out of a treatment room as quickly as possible and into inpatient beds, if available, and placing admission orders. Or if not, they patients can board in the ED while classified as inpatient status.28

Having a bed manager in the hospital allows for facilitation of a timely transfer from the ED to inpatient beds. Having real-time bed census availability allows the ED to know the number and type of beds available.29-31 Once admitted, the inpatient team as well as case management needs to work diligently on discharge planning. To help turn over beds on the inpatient side, discharge waiting rooms can be used to hold patients who are stable pending discharge instructions.32,33

Joint Commission Recommendations for Boarding

In September 2012, the Joint Commission published revisions to Leadership (LD) Standard LD.04.03.11, known as the “patient flow standard,” in the 2012 Update 2 to the Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals. It is recommended that boarding time frames not exceed 4 hours. The 4-hour time frame is not being imposed as a national target or requirement for accreditation.9 The decision to not have this as a quality metric likely is multifactorial, but at least sets a benchmark and a recognized standard to educate leadership to target.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

Boarding and crowding is common in emergency care, but it does not have to be. It is critical that physicians advocate for an efficient work environment that allows them to provide the care patients need. Get engaged by:

- Visiting the Hospital Compare website at https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html to see how your workplace fares on measures related to crowding and boarding.

- Educating your legislators and hospital administrators about the clinically important impact of boarding and crowding on patient care.

- Advocating for programs in your hospital to decrease boarding and improve patient flow.