Ch. 10 - Reforming Fee-for-Service — Paying for Performance

Erik A. Berg, MD; Jesse Schafer, MD

Pay-for-performance (PFP) is a health care financing strategy that aims to improve health care quality by financially incentivizing provider performance on quality metrics. Quality metrics are predetermined measures related to processes of care that are associated with positive health outcomes or efficient use of health care resources.1 Traditionally, physician reimbursement is tied to how much a provider does in terms of tests, procedures, or seeing more patients, regardless of indication, outcome, or patient satisfaction. This model is known as fee-for-service (FFS) and is one of the drivers of expanding health care costs in the U.S.2

Despite broad agreement over the concept of paying providers based on value rather than volume, there is considerable controversy on how exactly to measure value and to implement incentive payments based on the measurements.

In an effort to incentivize quality care and contain costs, CMS adopted the concept of value-based purchasing (VBP), which ties reimbursement to consensus-based quality measures and resource utilization measurements.3 Quality metrics are meant to standardize and compare the quality and delivery of care and account for the context of where that care is delivered. As such, quality measures were developed for providers and groups as well as hospital inpatient and outpatient settings. Reporting performance on these quality measures allows for comparison and transparency and is an essential part of VBP. VBP is the underlying principle behind the shift from FFS to PFP. In this chapter we will discuss the shift toward PFP through the implementation of quality measures.

The Rise of Quality Measures

In the past 30 years, CMS has shifted from a FFS model to a PFP model, recognizing that one way to reform FFS is to incentivize the use and reporting of quality measures.3,4 The Hospital Quality Initiative (HQI) was rolled out by CMS shortly after publication of two reports from the Institute of Medicine: “To Err is Human” in 1999 and “Crossing the Quality Chasm” in 2001.5 The goal of the HQI is to support and stimulate quality care by collecting and distributing objective and easy-to-understand data on hospital and provider performance across several domains.

Initially, there were no incentives to report on quality measures in these domains, and providers did not have guidance about what they should be reporting. In 2003, with the passage of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, a “starter set” of 10 quality measures was defined. After the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) was launched in 2007, the number of quality measures had increased to 74.6 Quality measures are not specifically developed by CMS but through organizations, advocacy groups, or medical specialty societies. The National Quality Forum (NQF), Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI), and the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) are the largest of these organizations. With the passage of MACRA in 2015, the number of specialty-specific quality measures continued to expand.

The End of the SGR and Beginning of the Quality Payment Program

MACRA’s passage marked a key moment in the reform of physician payment. Under MACRA, CMS aims to incentivize high-quality and high-value care with payment incentives through the Quality Payment Program (QPP).7 Under QPP, providers can choose from two participation tracks, depending on practice size, patient population, location, or specialty. These tracks are the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System and Advanced Alternative Payment Models.

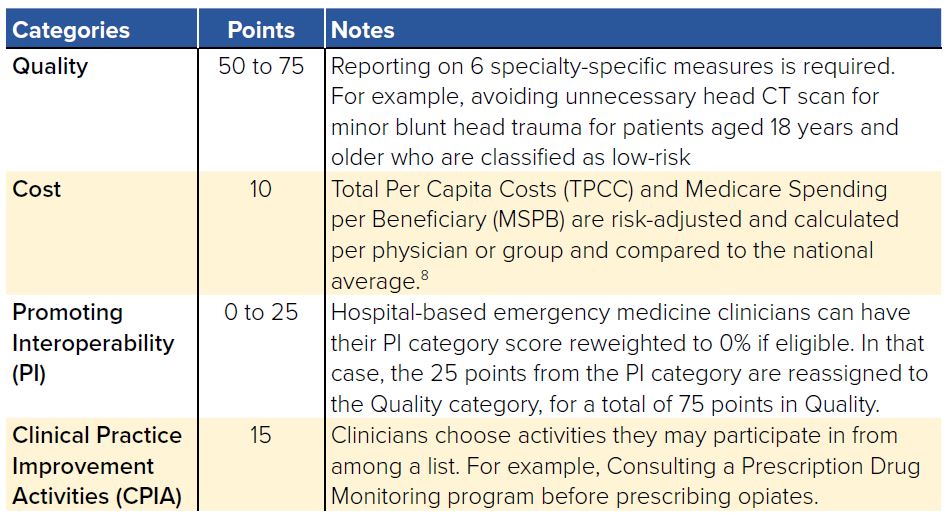

MIPS consolidates three older PFP programs — Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR MU), and the Value-Based Modifier (VBM) — into a new system in which providers receive an annual composite performance score based on four categories of metrics (Table 10.1).

TABLE 10.1. Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Performance Categories (2018)

Payments will be adjusted based on a provider’s composite score relative to an annual performance benchmark (either the mean or median of the composite performance scores for all MIPS eligible professionals). Providers with a MIPS composite score below the threshold will have their payments reduced. Likewise, providers with high composite scores will receive their positive payment adjustments. These positive and negative reward incentives are set to escalate from 4% to 9% by 2023.

The second track for provider participation in QPP is through alternative payment models that meet CMS’s “advanced” criteria (required use of certified electronic health record technology, provider pay based on quality metrics similar to MIPS, provider accountability for “more than a nominal amount” of financial risk for monetary losses). In this arrangement providers face more downside risk, but are also eligible for higher bonus payments, including an annual 5% payment bonus as well as 0.5% higher base rate (as compared to

MIPS) beginning in 2026 (0.75% versus 0.25%).

Emergency physicians have the ability to participate in MIPS as either individuals or part of a group. The Clinical Emergency Data Registry (CEDR) developed by ACEP is one means for emergency physicians to comply with this reporting process in a specialty-specific way. Participation in Advanced APMs is currently more difficult, if not impossible, for emergency physicians. In CMS’s list of Advanced APMs, acute unscheduled care is not directly addressed, leaving many emergency physicians without a mechanism to participate in Advanced APMs.8 In response, ACEP developed a proposal called the Acute Unscheduled Care Model (AUCM) that provides the opportunity for emergency physicians to participate in an Advanced APM.9 The overriding aim of the AUCM is to align the efforts of emergency physicians with CMS’s goal of rewarding physicians for providing value rather than volume. Rather than simply characterizing emergency care as expensive and targeting a reduction in its use, the AUCM seeks to address the role EM can play in delivering value. As proposed, the AUCM would reward and facilitate post-discharge care coordination in the ED, allowing emergency physicians to safely discharge more patients. In order to ensure that discharges are safe and appropriate, the model calls for monitoring post-discharge events including death, repeat ED visits, inpatient admissions, and observation stays.

Current Quality Metrics

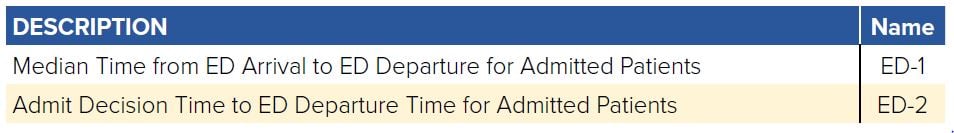

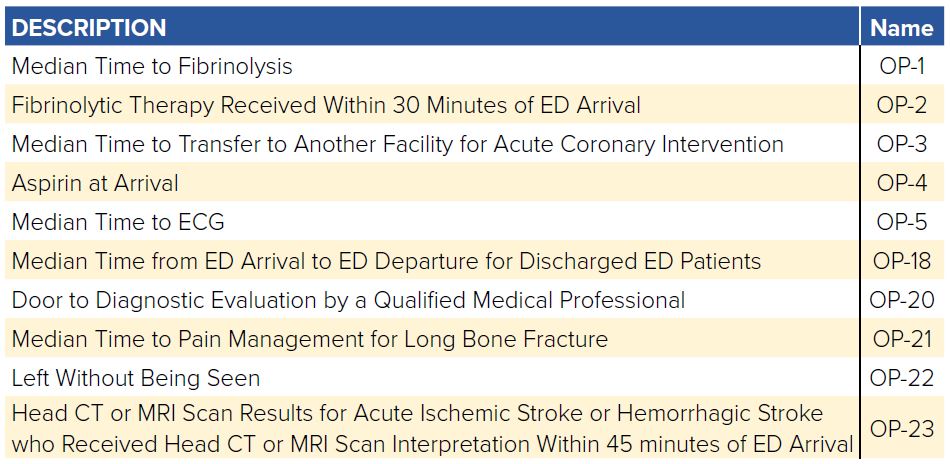

Just as the QPP aims to incentive individual providers to deliver value in health care, CMS focuses on value-based purchasing at the hospital level through Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) and the Outpatient Quality Reporting (OQR). Hospitals that do not meet the IQR/OQR reporting requirements face 2% point reduction in annual payment update (APU). To promote transparency, CMS publishes how each hospital performs through the Hospital Compare website. This public site allows beneficiaries to make decisions about how and where they access care based on the hospitals’ quality metrics. Additionally, as part of the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) under the ACA, hospitals can see up to a 3% reduction in reimbursement if their 30-day readmission rates for pneumonia, heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction exceed the target rates.8

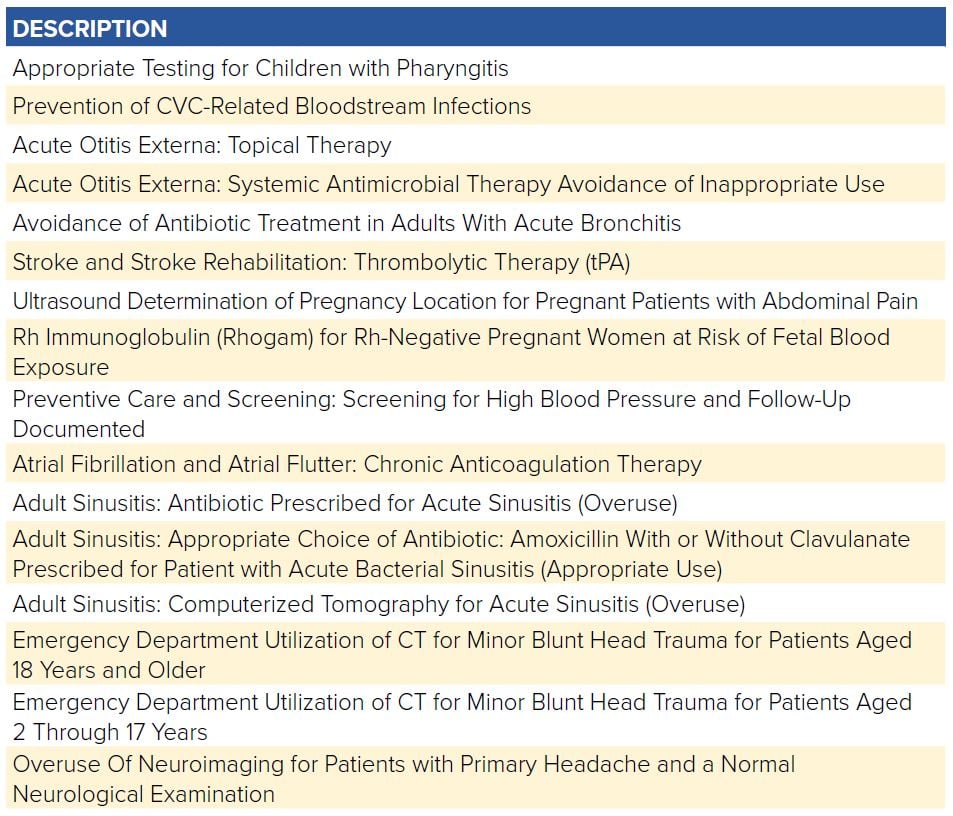

There are now an expanded number of quality measures related to EM as outlined in Table 10.2. Each metric will have a defined population, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the methods for determining success. For example, when treating children with pharyngitis, the population includes children ages 3-18 with a diagnosis of pharyngitis who had antibiotics ordered. Children on hospice are excluded. The successful completion is if a strep test was performed. Failure to test will qualify as a failure of the metric. It is important that providers understand the details and monitor their performance scores to ensure that their reported quality is accurate to their care. As their scores will follow them in their career when they move institutions, it is in each provider’s interest to ensure accurate data.

TABLE 10.2. QPP Measures Relevant to Emergency Care in 2018

TABLE 10.3. IQR Measures Relevant to Emergency Care

TABLE 10.4. OQR Measures Relevant to Emergency Care

Challenges and Controversy

Despite broad agreement over the concept of paying providers based on value rather than volume, there is considerable controversy on how exactly to measure value and to implement incentive payments based on the measurements. There are 3 major arguments over PFP programs.

Immature Measures

Critics argue that the current state of performance metrics does not accurately account for a physician’s contribution to producing value because current metrics rely too heavily on indicators that are easy to measure. Metrics that meaningfully capture value do not yet exist, in part because the core competencies of some specialties do not easily lend themselves to measurement. For example, current OQR measures for emergency care include only process measures: door to doctor time, time to pain meds for long bone fractures, CT for stroke read within 45 minutes, admission decision time to inpatient bed time, median length of stay (LOS) in the ED, median LOS for admitted patients, and ED volume. Current metrics do not capture key aspects of emergency care, which involve diagnostic investigation of undifferentiated complaints (eg, chest pain and abdominal pain) and clinical decision-making based on limited information (eg, does this patient need a workup for acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or both?) rather than diagnosis based quality measures.10 Yet because we lack metrics for these skills and characteristics, OQR measures include performing an ECG on atraumatic chest pain patients, an ultrasound on pregnant patients with abdominal pain, and giving Rhogam for Rh-negative pregnant women at risk of fetal blood exposure. Process measures such as these have a role in measuring quality; however, taken alone, they fail to account for the overall value and complexity of emergency care.

Inadequate Risk Adjustment

There is a large body of evidence showing that a patient’s sociodemographic factors (eg, age, race, primary language, education, income) influence outcomes — and therefore also affects outcome performance measures for physicians.11-14 Organizations such as the NQF have argued that performance measures should be risk-adjusted for patients’ sociodemographic factors to ensure that physicians taking care of vulnerable populations are not financially penalized for factors outside their control. Critics of pay-for-performance argue that the current state of risk-adjustment science is not yet sophisticated enough to be confident in the fairness of performance metrics. As such, inadequate risk adjustment potentially poses 2 harmful unintended consequences: 1) It provides a perverse incentive

for physicians to avoid taking care of disadvantaged patients, and 2) It may exacerbate health disparities by depriving providers of the resources they need to provide quality care to disadvantaged patients.

Motivation

Assuming there were better metrics, it seems like paying physicians based on their performance on these measures should be able change their behavior to produce better clinical results. However, behavioral science literature challenges the notion that financial incentives can improve performance on cognitively complex tasks (eg, clinical medicine).15 Tackling complex tasks seems to require sources of intrinsic motivation — such as purpose, mastery, or altruism — that are common among physicians.16 When financial rewards are applied to complex tasks, however, these financial incentives can actually undermine, or “crowd out,” intrinsic motivation.17 So rewarding physicians based on particular performance measures risks sapping their intrinsic motivation to provide high-quality care in general rather than on just a few activities being measured.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

The transition from pay per volume to pay for quality continues to advance and will transform the landscape of health care. Advocacy includes:

- Engaging in developing quality measures relevant to emergency medicine.

- Taking an active role in defining measures that are accurate, fair, and meaningfully influence outcomes that matter to patients.

- Implementing relevant quality metrics in our practices.