Ch. 11 - Delivery System Reform

Kenneth Perry, MD; Jessica Alvelo, MD; Emmagene Worley, MD

Every discussion of health care reform is underpinned by the concern that the cost of health care is growing at an unsustainable rate. As the Baby Boomer generation continues to retire, keeping Medicare solvent is a constant concern. The ACA addresses this by incentivizing increased value in health care by rewarding groups of practitioners for decreasing costs while improving quality. It’s within these environmental pressures that dramatic system reform is occurring, with new entities such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACO), bundled payments, integration of disparate parts of the health system, and innovative ventures.

The landscape of health care delivery is changing rapidly. Integration is occurring between physician groups, as well as different levels of the delivery system.

Accountable Care Organizations

The ACA established a new model of payments for practitioners who currently receive fee-for-service payments. If a group of practitioners can reduce costs, they will be allowed to receive a percentage of the savings they accrue. This shared saving model, the ACO, provides the framework for the cooperation of multiple practitioners.

According to Medicare, ACOs are “groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers who come together voluntarily to give coordinated high quality care to their Medicare patients.”1 The only requirement for involvement in the ACO is that all parties must be allowed to accept payments from Medicare. From the patient’s perspective, an ACO is just another acronym that does little to change their interaction with the medical industry. ACOs are non-binding; that is, unlike HMOs, patients are not restricted to see only physicians and practitioners within their ACO for their Medicare benefits to cover the costs. ACOs have a much greater impact on providers than patients. The incentive for the practitioner within an ACO is to reduce the growth of the health care costs and to provide better quality care to patients. To gauge that quality of care, CMS has instituted specific measures for ACOs. If an ACO can provide higher quality care (as demonstrated by the quality measures) and reduce costs, the entire ACO will be able to “share” in those cost savings.1,2

ACOs have worked to change the model of coordinated care. They have made

interdisciplinary groups part of the same pool of payment, attempting to connect

reimbursement with increased coordination of care. Unfortunately, it has not yet

been determined how emergency medicine will fit into this new model as most

do not include emergency physicians.3 This offers both opportunity and risk: We

can create our niche and solidify our standing in the institution or risk ceding our

stature, voice, and reimbursement to those without EM forefront in their minds.

Bundled Payments

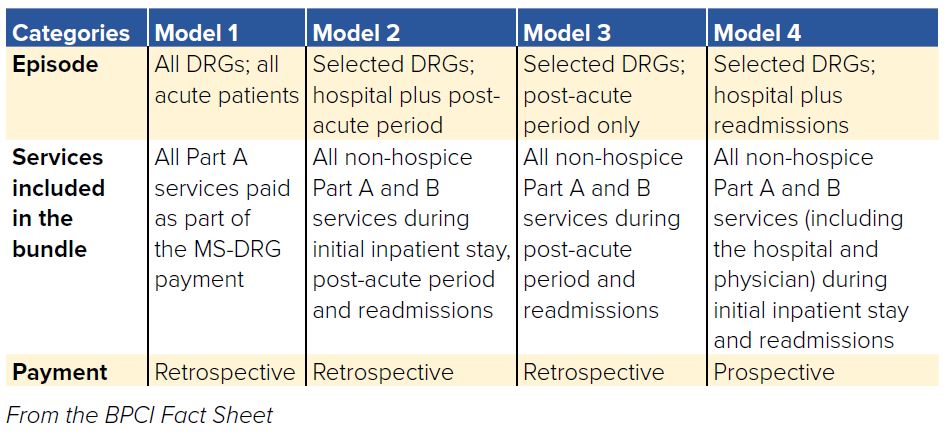

The concept of bundled payments, and specifically the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative, is part of a long effort to align incentives for hospitals and providers to increase quality and decrease the cost of health care. The BPCI has been going through multiple phases spearheaded by CMS with 4 payment models.4 These payment models define an episode of care, a time course, and a payment structure. An “episode of care” represents all the services provided for the patient during a specified period of time for a particular diagnosis related group (DRG), such as a congestive heart failure exacerbation or a total knee replacement. There are 3 retrospective payment models and one prospective model. The retrospective structure works by comparing the historical

cost of a particular episode of care with the amount actually spent for the patient visit. The hospital or organization is paid by Medicare at an agreed upon 1-3% discount from historical costs, and at the end of the episode of care, the actual cost of the episode is compared with the historical cost. If there is a cost savings, the hospital and providers receive a portion of the savings, called a “gainshare.” If the actual visit exceeds the historical cost, the hospital must pay a portion of the difference back to CMS. In the prospective model, CMS pays the hospital a prospectively determined amount of money to be used for the entirety of the episode, encompassing all payments to providers, the entire inpatient stay, and any readmissions.

According to a Lewin Group analysis of the bundled payment program, initial results showed that the retrospective model of bundled payments decreased expensive skilled nursing facilities stays and increased less expensive home health agency utilization.6 In addition, readmissions were decreased in comparison to standard Medicare reimbursements, but ED visits without hospitalization increased proportionately. These demonstration programs demonstrate that there is an opportunity for better coordination in the narrow areas studied, but time will have to tell if broader improvements can be made with bundled payments.

TABLE 11.1. Outline of the 4 Models

These payment systems impact emergency medicine in several ways. After a bundled payment system is implemented, ED visits after the initial hospitalization usually remain stable as shown in the Lewin Group analysis of bundled payments.6 Emergency physicians will thus be under further pressure to keep readmissions to a minimum while continuing to see recently hospitalized patients with complications. This necessitates greater coordination and services available in the ED. As the ACEP ACO Information paper states, emergency medicine may need to diversify the options for management of patients evaluated in the ED who are not admitted as inpatients.” This includes creating observations units, restructuring traditional outpatient services such as Holter monitors, and allocating resources for follow-up calls, coordination of home health agencies, or rehab referrals.7 In addition, the Medicare models will pay a lump sum to either the hospital or appointed outpatient physician group.4 The allocation of the reward is left up to the awardee, and the distribution of the reward is dependent on the institution. Emergency physicians must be involved to ensure appropriate participation in gainshare allocation and the resources to improve the care coordination.

Health Care Consolidation

There has been a trend toward consolidation in the health care industry, occurring primarily through hospital mergers, the development of ACOs, and the buy-out of physician practices by large health systems. Consolidation in the marketplace is at its highest levels in the past decade, with the number of hospital mergers doubling between 2009 and 2012.8 Data also indicate that the percentage of physicians employed by an integrated delivery system increased from 24% to 54% between 2004 and 2012, which is represented within EM as well.8

The ACA is working to change incentives for providers by moving from a fee-for-service model to a value-based reimbursement model encompassing bundled payments, capitation arrangements and ACO/shared savings models. Within this new value directed paradigm, it becomes extremely challenging for small independent groups and individual hospitals to deliver the necessary degree of care integration. There are also higher reimbursement rates for those able to charge facility fees for outpatient visits in large health systems that are not available to independent providers, further increasing the pressure to consolidate into large health systems. The current regulatory and market conditions offering unprecedented levels of uncertainty in terms of reimbursement and technology demands have driven physician groups to move towards acquisition.9

Emergency physicians may benefit from practice consolidation due to their access to larger hospital networks, the financial security of a large corporation, and the ability to benefit from the greater reimbursement negotiation power of a larger group. Additionally, as physician groups are now called on to report quality metrics and build IT systems, doctors in smaller EM groups are left to handle these tasks on their own in their off-time, due to lack of management and administrative infrastructure. Acquisition by large staffing groups has become increasingly appealing to physicians, as they can then focus on clinical practice rather than having to invest the capital to become adept at navigating the regulatory reporting requirements. Opponents of consolidation in EM physician

practices argue that physician ownership of practices is essential to ensure that incentives are aligned to provide good patient care rather than to maximize profits, which is a concern of relinquishing control of a practice to non-clinicians.10

New Types of Health Care Consolidation

Integration is not just happening at the physician group and hospital level, but rather all across the spectrum. Physician groups merging would be an example of horizontal integration, where a merger occurs at the same level of a supply chain. If different levels of a supply chain, for instance health insurers and pharmaceutical companies, merge it is called vertical integration. A great example of vertical integration is Optum Health. Optum does data analysis, health insurance, employs physicians and has a pharmacy benefit manager. This type of integration is occurring throughout the sector with CVS/Aetna, Cigna/ExpressScripts, and Humana/Kindred being just a few examples of pharmaceutical companies and health insurers merging. The impact of these new consolidations of different parts of the health care system that have not been traditional partners will introduce new pressures on the providers and patients with unknown outcomes.

Greenfield Healthcare Delivery Ventures

Recently, three non-health care industry giants have teamed up to address health care costs in America. The CEOs of Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JP Morgan announced in January 2018 the formation of a new health care venture aimed at decreasing cost and increasing value. This is just one more example of vertical integration occurring within medicine. To start, the company will be enrolling their own employees and dependents, amassing more than 1 million potential patients. While operational details were not publicized in 2018, they named Dr. Atul Gawande as CEO.11,13,14 They identified 3 targets that add costs to the current health care system: pharmacy management benefit companies, insurance brokers, and insurers. Their vertical integration is impressive with Amazon owning PillPack, an online pharma company, and Berkshire Hathaway owning Teva Pharmaceuticals, a generic pharmaceutical company. They posit that by removing these “middle men” from health care delivery and facilitating a more direct stream between patients and their health care, costs will decrease.12 Until concrete details are released, the impact is unclear. But with more than 1 million patients between them, one thing is certain: This new health care venture is something to watch.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

The landscape of health care delivery is changing rapidly. Integration is occurring between physician groups, as well as different levels of the delivery system.

Advocacy here includes:

- Staying engaged in the landscape of health care delivery.

- Understanding the ultimate effect of mergers on patient care.

- Advocating for the practice of emergency medicine in this changing environment.