Ch. 28 - Social Determinants of Health

Callan Fockele, MD, MS; Hannah Janeway, MD; Dennis Hsieh, MD, JD

Background

Sheldon has been to the emergency department most nights this week. He is homeless, has congestive heart failure, and is here for his nightly sandwich, furosemide, and nap. Uninsured, Sheldon has given up on filling his medications. Instead, he comes to the ED for medications, food, and shelter.

Emergency physicians are experts on the social issues affecting the health and wellbeing of their community, and it is their obligation to stand up, show up, march, lobby, and advocate on behalf their patients.

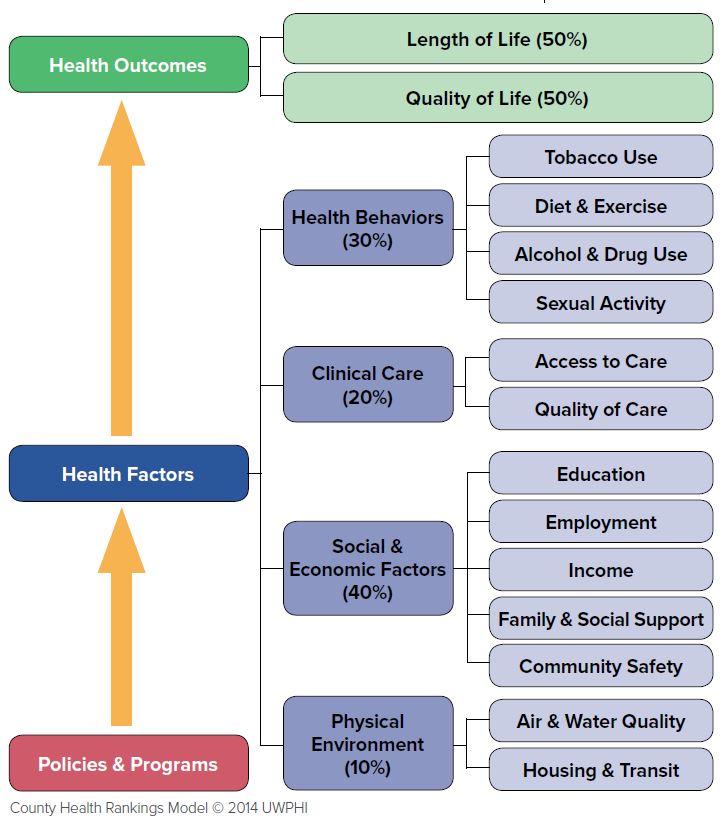

Social circumstances have a significant impact on health, and these problems often manifest in the ED. As the front-line providers of the health care system, emergency physicians care for patients in crisis. Although their chief concern may be chest pain or headache, many ED patients also face issues of homelessness, food insecurity, income inequality, racial discrimination, and addiction. Collectively these social, economic, environmental, and legal issues are known as the social determinants of health (SDOH).1 While emergency physicians focus on treating acute illness or acute manifestations of chronic illness, it is important to recognize that many of these illnesses are the downstream consequences of unaddressed SDOH. The County Health Rankings & Roadmaps created an overall modeling for length and quality of life in all counties across the U.S. and found that SDOH account for 50% of health outcomes — length of life and quality of life — whereas clinical care accounts for only 20% (Figure 28.1).2 Unsurprisingly, recent research shows that addressing SDOH improves health outcomes while decreasing costs.3

FIGURE 28.1. Impact of Social Determinants of Health

Sheldon’s case exemplifies how homelessness leads to an inability to adhere to the recommended diet and medications for his condition and exacerbates his CHF. Many ED patients have chief complaints that are directly related to their living situation. Providing stable housing has shown remarkable outcomes in terms of savings, improved health, primary care connection, and decreased ED utilization.4-6

However, addressing SDOH is a challenge for emergency physicians, given busy EDs with limited resources.3 Medical education does little to train physicians to address these problems.7 Furthermore, data compiled by the AAMC shows that most medical students come from middle or high-income families with parents who have college or graduate degrees8,9 and thus may have a poor understanding of the realities of vulnerable groups. Emergency physicians are often hesitant to ask about SDOH concerns and may defer to social workers when issues arise.10-12 In this chapter we put forth a framework for emergency physicians to learn, educate, screen, address, and advocate for patients’ SDOH needs.

Educating Yourself

To date, there is no comprehensive website or reading list for self-directed learning on SDOH in the ED. The International and Domestic Health Equity and Leadership (IDHEAL) section at UCLA has a suggested reading list with short descriptions that have been vetted by its members.13 For beginners, the 2009 PBS series “Unnatural Causes…Is inequality making us sick?” (https://www.unnaturalcauses.org) provides an overview about SDOH. For more advanced learners, SIREN (Social Interventions Research and Evaluations Network) at UCSF has an extensive Evidence Library that contains hundreds of articles looking at social interventions in medicine.14

Educating Learners

Medical students, residents, and academic/clinical faculty should advocate for greater emphasis on SDOH throughout medical education as it is a factor in health outcomes. As the front line of the health care system, emergency physicians witness the everyday effects of homelessness, hunger, and other SDOH on patients; therefore, EM providers have a particular interest in learning how to address SDOH.

Medical School

In the pre-clinical years, a formal social medicine curriculum, similar to those at the Alpert Medical School15 and The Pritzker School of Medicine,16 should be instituted to accurately reflect the patient population and teach basic principals in SDOH. Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) can be reformatted with new cases highlighting SDOH and grading can include students addressing SDOH in their evaluation and plan.

In the clinical years, emergency medicine clerkships and sub-internships should teach principles related to SDOH and evaluate the student based upon these principles as part of the history taking and intervention. If a checklist is given for basic procedures, interviewing a certain number of patients in detail about their SDOH challenges/barriers should be included. Residents and faculty can also educate students during teaching rounds or at the bedside.

Residency

The ACGME recently found there is currently a “substantive deficiency in preparing residents and fellows to both identify and address disparities in health care outcomes, as well as ways to minimize or eliminate them.”17 However, no education requirement or standard has been established to remedy this. In general, SDOH should be an integral part of the residency curriculum and be incorporated as a component of resident conferences, simulations, journal club and bedside teaching and be not relegated to a single lecture.18

IDHEAL has a collection of short bedside teaching modules with teaching guides that can be taught on shift by any interested faculty or resident.19 Residents should be given real-time feedback during presentations about addressing SDOH when appropriate. Several residency programs have SDOH “tracks” for interested residents focused on SDOH research and career development. One such program is Stanford’s Global and Population Health focus in their ACCEL program, which allows residents to focus on scholarly projects and advanced professional development, or Harbor-UCLA’s Social Emergency Medicine/Health Equity Selective Track; these programs can serve as models for other residency programs. Residents should also be encouraged to interact with community organizations on social issues pertinent to their patient populations to narrow the gap between health care and the community and help them gain an improved understanding of SDOH.

Fellowships

There are SEM, health policy, and population health-related fellowships, many of which are outlined in the EMRA Fellowship Guide.20 Examples include the Stanford and UCLA (IdHEAL) population and social EM fellowships and the National Clinical Scholars Program.

Addressing Social Determinants of Health in the ED

Identifying SDOH barriers through systematic screening as outlined below can remove some of the burden from the provider. However, the provider also has the responsibility to inquire about social factors that influence disease states and prevent treatment success. Not infrequently, social determinants of health are uncovered in the process of understanding treatment failures, poor management of chronic disease, or frequent recidivism. For example, since Sheldon cannot afford his CHF medications and does not have transportation to the pharmacy, he is failing outpatient CHF management.

Recognizing SDOH During a Patient Encounter

Due to the fast-paced nature of the ED and provider reliance on pattern recognition, it is easy to fall back on assumptions instead of probing for understanding. Implicit biases are attitudes, stereotypes and conditioned thinking that affect our understanding and interactions with the world and others in an unconscious manner. A recent systematic review indicates that health care professionals have the same rate of implicit bias as the general population and that this affects patient care in terms of treatment for acute myocardial infraction, asthma, and pain.21,22 Sometimes it is faster and easier to blame patients for their lack of self-care than to understand the complex web of factors that affect a patient’s ability to adhere to a treatment regimen. While the time-limited nature of emergency medicine makes it impossible for providers to screen patients fully for SDOH during ED encounters, emergency physicians should take the time to ask pointed questions that can improve treatment plans and improve patient outcomes.

Emergency physicians with an interest in the role of implicit bias in EM can take the Implicit Association Tests (IAT) to better understand the role of implicit bias in their practice.23 Further reading is available through IAT modules24 or through targeted

readings or a video series put together by UCLA.25 Based on these modules, emergency physicians can incorporate additional questions to understand potential barriers to treatment success and to probe treatment failures.

Understanding Your Role in Addressing Social Determinants

Emergency physicians are team leaders, and their attitudes and biases will set the tone for the department during any given shift. To set a positive tone, emergency physicians should remind the team that their goal in the ED is to serve as healers and advocates for the most vulnerable. Nurses can be helpful in understanding patient barriers because they spend more time at the bedside. Engaging other members of the team about potential barriers to care can emphasize the importance. The physician is also responsible for reorienting team members when disparaging comments are being made about patients. It is easy to blame patients for their disease, and a simple reminder of SDOH can be effective. For instance, in the case of an asthmatic child repetitively being brought to the ED for exacerbations, focusing on the built environment or access to affordable clean housing can set an example for other team members.

Although emergency physicians cannot always address SDOH individually, they can involve of social work, convene stakeholders, and advocate the allocation of resources for identifying and addressing SDOH. Establishing programs or building community partnerships that address gaps in resources offered by social work and hospital resources can be a great benefit to emergency patients. The Levitt Center at Highland Hospital offers a resource list on its website outlining successful projects at a variety of institutions.26

Emergency physicians can reorient the team and create an environment focused on understanding vulnerable patients. Emergency physicians can be a leader and work with other departments on addressing gaps in resource provision. If a physician’s group or academic program has a journal or book club, dedicating a month to SEM could be beneficial for all.

Identifying/Screening for & Addressing SDOH Concerns

ED providers must perform a needs assessment in order to systematically address the SDOH that affect patients’ health. We recommend implementing a SDOH screener, as providers generally have a poor understanding of patients’ SDOH priorities and needs.27,28 Various patient screening tools have been proposed over the years to screen for upstream social issues that may contribute to poor health outcomes.29,30 Small studies show that concerns around housing, food, income/employment, and access to care are often the most prevalent27 and should be the starting point of screening. However, questions should be discreet and actionable to avoid frustration — so base questions upon what resources are available locally.

Integrating screening questions into the ED workflow can be challenging. Most EDs do not have extra funding or staff available to implement a dedicated screen. Some of the questions, such as those screening for intimate partner violence, may already be part of the workflow. It’s crucial to work with nursing, operations, and social work to determine where in the ED visit these additional questions should be added.

When a patient screens positive, a multifaceted approach is needed. Handouts and electronic resource directories such as 1 Degree (www.1deg.org) are the easiest, but the least effective. Most areas also have access to a telephonic resource directory, such as 2-1-1, where individuals can call in and receive real-time assistance with searching for resources. Social work can provide a higher level of service, but many EDs do not have 24/7 social work coverage. Finally, building out partnerships with local community organizations that are funded to address many of these issues can lead to efficacious warm handoffs where a patient is directly connected to an individual at the organization who can then work with the patient to meet his/her need. However, often there are insufficient local resources to meet patients’ SDOH needs, highlighting the need for further advocacy.

Advocacy

As a physician and statesman, Rudolf Virchow saw the world as a social experiment of economic and political forces on health: “Medicine…has the obligation to point out problems and to attempt their theoretical solution: the politician, the practical anthropologist, must find the means for their actual solution. The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and social problems fall to a large extent within their jurisdiction.”31 In addition to their clinical work, emergency physicians have the power, knowledge, and privilege to

advocate for their patients outside the hospital walls.

Know your power.

Emergency physicians witness the downstream effects of the SDOH every day. They are the gateway to the health care system, and their doors are always open to the most vulnerable patients. Because of their clinical exposure to patients’ SDOH concerns, emergency physicians are experts on the social issues affecting the health and wellbeing of their community, and it is their obligation to stand up, show up, march, lobby, and advocate on behalf their patients.

Some residencies have created SEM interest groups committed to meeting a couple hours per month to digest issues related to the SDOH. These events range from happy hours and journal clubs focused on public health to town hall meetings and rallies. Local work is shared with the wider EM community through social media using #SocialEM.

Know your patient population.

Although emergency physicians are intimately familiar with the social determinants of health through their clinical work, their advocacy should be informed not only by anecdotal data but also by evidence-based, community driven issue identification. A recent systematic review of SEM literature found a high prevalence of homelessness, poverty, housing insecurity, food insecurity, unemployment, difficulty paying for health care, and difficulty affording basic expenses among emergency department patients.32 Further perspective can be provided by community based participatory research (CBPR), which actively engages community members in all aspects of the research process, providing a step toward political action. For example, a study in New Haven used CBPR to identify and interview key stakeholders working on homelessness within their community, propose the development of a medical respite for homeless patients discharged after an acute hospital visit, and advocate for funding from the Connecticut legislature. Their intervention decreased 30-day inpatient readmission rates for homeless patients from 50.8% to 21.6% during their study period.33

Know your hospital and community partners.

Instead of advocating for patients in isolation, emergency physicians may achieve greater success by partnering with other health care and community partners. Many, such as social workers and volunteers, work within their health system. However, the issues affecting their patients are undoubtedly interdisciplinary, and many outside of medicine work on these issues from different vantage points including local government, public health, and public policy. Additionally, community organizations, including homeless shelters, hygiene centers, food banks, and needle exchange programs, already serve their patient population and are natural allies.

Organizing a SEM residency conference is a unique opportunity to invite health care and community partners to participate in panels and workshops on substance use, homelessness, immigration, and other issues related to SDOH. This will not only provide educational value but also an opportunity for consortium building.

Know your politicians.

Emergency physicians shape health policy by working with elected officials, ranging from city council members and mayors to members of Congress and the president. Despite differences in authority and influence, officeholders are elected and, thus, are dependent upon their constituents for power. For this reason, emergency physicians must target elected officials, share patients’ stories, and hold them accountable for addressing SDOH.

This work begins with identifying local political allies. Good clues as to who might be helpful are officials who serve on medically related committees or task forces, have sponsored relevant bills, or whose districts are home to medical and social service facilities. Informed by this research and clad in white coats, emergency physicians can attract public attention by asking questions during town hall meetings, organizing protests during public events, publishing letters to the editor, and taking to social media. Additionally, the influence of physicians can also be felt privately through issue-focused office visits and coordinated calls.

Know your lobbying bodies.

Strengthened by numbers and, often, financial backing, medical interest groups lobby elected officials and influence health policy. These institutions vary widely in their representation and goals. Professional organizations such as EMRA and ACEP not only provide state and national advocacy for the specialty but also leadership roles that allow residents to write policy, meet with politicians, and enact systemic changes that affect their patients’ lives. Both ACEP and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine recently recognized the importance of these issues and formed the Section on SEM and the Interest Group on SEM and Population Health, respectively.

In contrast, grassroots organizations thrust their specific issues into the political dialogue. For instance, Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR) educates policymakers around the health threats of nuclear proliferation, climate change, and income inequality, and the American Foundation for Firearm Injury Reduction in Medicine (AFFIRM) addresses the epidemic of gun violence by funding and promoting firearm injury research.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- Ask for social determinants to be included in your didactic curriculum.

- Create a team-based environment that acknowledges and addresses patients’ social needs.

- Perform a social needs assessment of your patient population, and consider using these data to inform a quality improvement project.

- Work with partners at the health system, local, state, and/or national level to advocate on behalf of patients to address patients’ social needs.